Diversity has become a business buzzword in recent times, with numerous C-suite executives viewing it as simply a tick-box exercise, alas. And yet a growing welter of evidence suggests the manifold advantages of utilising diverse supply chains – engaging suppliers from ethnic, racial and gender minorities – are too significant to be ignored.

In the UK there is much work to be done in this area, however, and in truth, when it comes to encouraging such a progressive approach, most of the world is some way behind pioneers in the United States. Indeed, the very idea of supplier diversity was triggered by the epochal American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

It is little coincidence that on March 5, 1969, less than a year after the Civil Rights Act, popularly known as the Fair Housing Act, President Richard Nixon, who had taken office only six weeks earlier, signed the game-changing Executive Order 11458 that stipulated government agencies and their contractors should partner up with minority-owned companies.

It soon became apparent that to prevent fraud, rigorous third-party certification was required; hence the National Minority Supplier Development Council (NMSDC) was formed in 1971 to determine which organisations qualified for minority business enterprise (MBE) status.

In the susequent four-and-a-half decades, a cluster of other national units have been established in the US to foster growth for diverse business types and address the needs of various affinity groups, including women, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals, and those with disabilities.

And now, even though the NMSDC, which aims to “support and facilitate MBE integration into corporate and public sector supply chains” by matching in excess of 12,000 certified MBEs to its “vast network of corporate members who wish to purchase their products, services and solutions”, has the likes of Apple, Google, Amazon, Walmart and more than 300 more top corporate organisations on its books, there remains a frustratingly backward-looking attitude at boardroom level, according to Joset Wright-Lacy, president of the organisation.

Waitrose is one company that works with a range of smaller suppliers to offer local products that differ from region to region

Last autumn she wrote, in Supply Chain Quarterly, about her “deep sense of urgency” to combat corporations questioning the importance of MBEs to their commercial relationships and supply chains. Calling such an outdated perspective “shortsighted” she warned: “[This] thinking can lead to the placement of artificial barriers in front of MBEs and usually leads to excuses for dropping support for supply chain diversity when corporate budgets are cut.

“There is clear and strong evidence that working with minority-owned suppliers provides business benefits for both buyer and supplier. Moreover, these relationships have a beneficial impact not only on local communities, but also on the national economy.”

Ms Wright-Lacy, who has praised department store chain Macy’s, and aerospace and defence giants Lockheed Martin, pointed to an NMSDC study from 2014 that revealed MBEs in America generate “more than $1 billion in economic output every day” and $401 billion annually. Additionally, in that same year NMSDC-certified MBEs were “responsible for the maintenance or creation of more than 2.2 million jobs and generated more than $48 billion in tax revenue to local, state and federal governments”.

Furthermore, a 2015 report by leading enterprise benchmarking firm Hackett Group claimed “on average, supplier diversity programmes add $3.6 million to the bottom line for every $1 million in procurement operation costs” and added that the high return on investment was undeniable.

We are seeing businesses wake up to the commercial benefits that a diverse supply chain can bring

In the same year McKinsey & Company published Diversity Matters, which examined proprietary data sets for 366 public companies across a range of industries in the UK, US, Canada and Latin America. “Our research finds that companies in the top quartile for gender or racial and ethnic diversity are more likely to have financial returns above their national industry medians,” the study says. “Diversity is probably a competitive differentiator that shifts market share towards more diverse companies over time.”

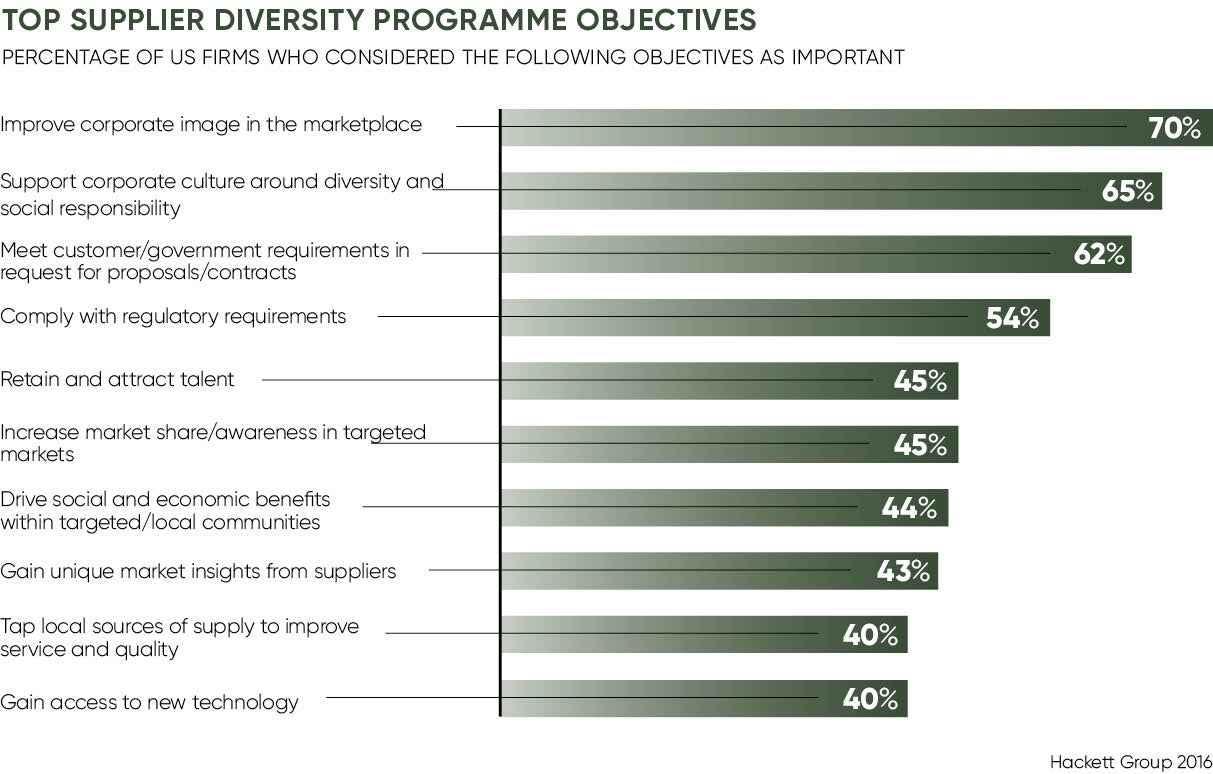

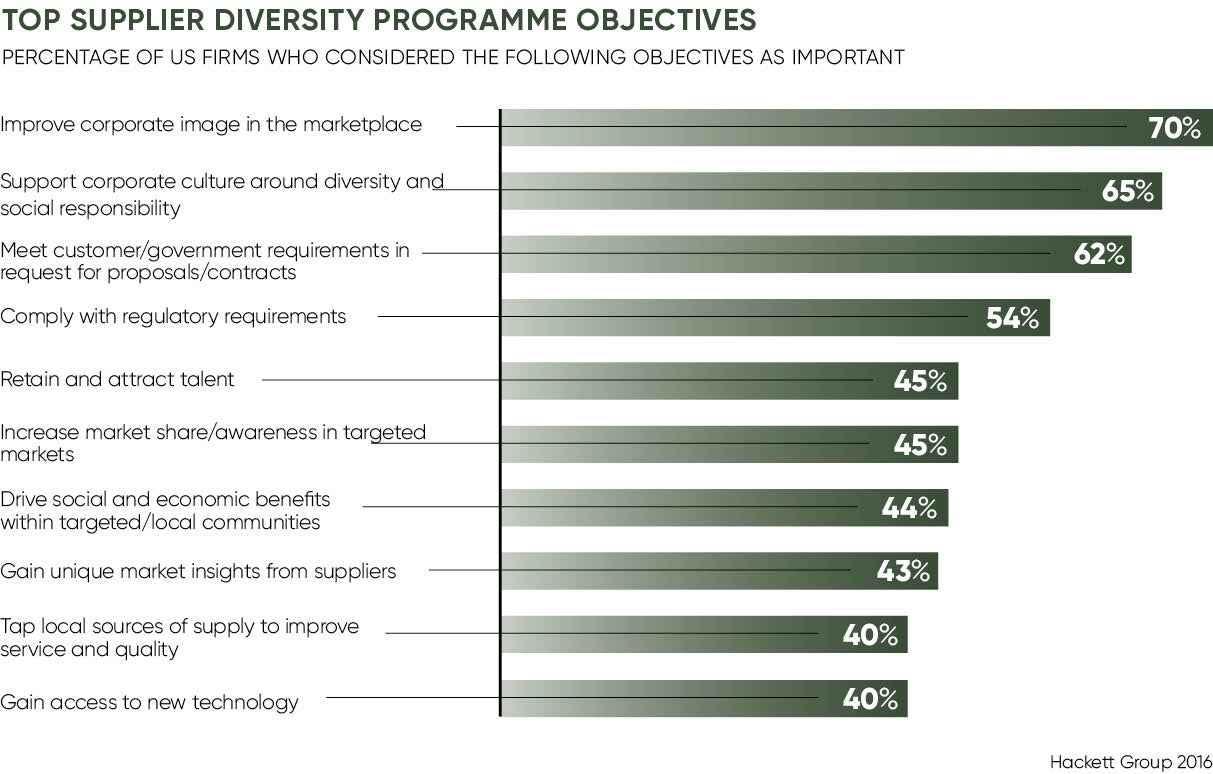

Away from a boosted bottom line there are a multitude of other reasons to establish and nurture a diverse supply chain. In Hackett Group’s 2016 Supplier Diversity Performance Study, research director and co-author Laura Gibbons says that having a diverse supply chain can be much more than a reputation builder.

“Supplier diversity is evolving from a check-the-box corporate social responsibility (CSR) requirement to a strategic enabler providing access to innovative products and increased market share in new and developing communities,” she says. “Top-performing organisations are taking advantage of this opportunity, and applying the tenets of social diversity to new areas such as supplier partnering, reputation management and global expansion with exceptional results.”

UK adoption

Slowly but surely UK organisations are beginning to cotton on. “Diversity used to be viewed by many companies merely as a way of fulfilling their CSR obligations,” says Leon Smith, procurement and supply chain consulting leader at London-headquartered PwC, “but now we are seeing businesses wake up to the commercial benefits that a diverse supply chain can bring. These are increased innovation, more agility leading to greater speed to market and the revenue growth opportunities for expanding customer base.

“Companies can drive greater levels of entrepreneurialism, innovation, agility and flexibility, and commercial impact by tapping into the different perspectives that a diverse supply chain can bring. Also it can help businesses move closer to their local community and customers, and ultimately help them appeal to a more diverse customer base.”

Professor Alan Braithwaite, chairman of supply chain and logistics consultancy LCP Consulting, lauds UK organisations Co-op and Waitrose for their forward-thinking attitudes in this space, but posits: “Diverse supply chains are more prominent in the US than Europe as CSR is more highly developed.” But he warns: “As smaller diverse suppliers are not as advanced, there is a risk that they lack the ability to stretch themselves when responding to sudden events.”

Conversely, Cheltenham-based business consultant Marc Lawn notes that organisations using diverse supply chains will have resilience built in because they are not reliant on a sole source for goods. “Having geographically diverse suppliers means you can potentially offer a more local supply option or a quick turnaround when circumstances require,” he says.

The biggest benefits are the diverse views around how you can improve and also the potential for developing innovative solutions to any problems that occur

“Smaller and agiler suppliers can generally ‘top up’ when there are issues in localised production, and that is a big benefit when you don’t want to be tied to large minimum-order quantities. They are generally not as price competitive, but could often offer a more personalised or higher quality service; for example, they may make the delivery to your facility for you or offer rapid overnight delivery.

“The biggest benefits, though, are the diverse views around how you can improve and also the potential for developing innovative solutions to any problems that occur.”

The UK’s equivalent to America’s NMSDC is Minority Supplier Development UK (MSD UK), which was set up in 2006 to promote diversity and inclusion in the supply chain. “Minority-owned businesses in the UK face a number of challenges, such as access to capital and mainstream supply chain opportunity to scale up their businesses,” says MSD UK’s chief executive Mayank Shah.

“This greatly affects their long-term sustainability. Data gathered from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and other sources indicate that despite the higher level of minority-owned startups being established here, compared to the rest of the world, after three years those levels drop dramatically; the principal factor for this is a lack of capital and opportunities.”