Renewables such as wind and solar photovoltaics, or PV, now provide almost three tenths of global electricity. The industry’s spectacular growth ovder the past two decades has been supported by global supply chains that have helped to drive down costs. But the coronavirus pandemic threw an almighty spanner in the works, with border closures, lockdown restrictions and component delays slowing the progress of many clean energy projects.

“These ventures subsequently ran the risk of increased construction costs, as project developers tried to source parts from elsewhere,” says Somik Das, senior power analyst at GlobalData.

Quarantine measures also reduced the workforce on some construction sites, he adds, and contractors reliant on international labour were further impacted by travel restrictions.

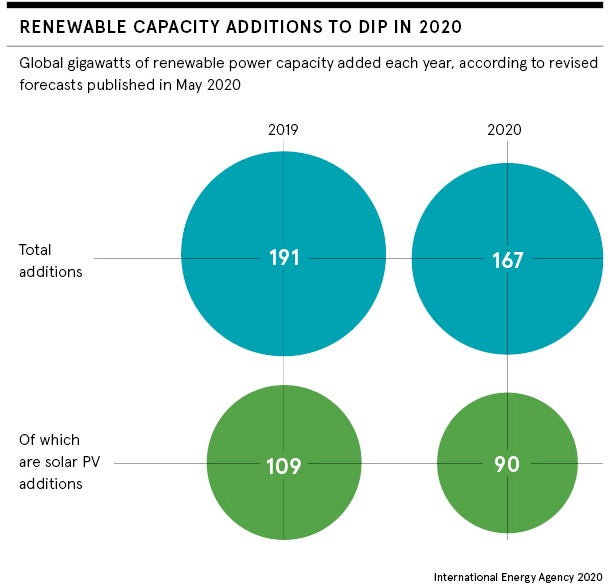

As such, it’s perhaps no surprise that the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts the amount of renewable power capacity added in 2020 will be down 13 per cent on 2019. However, the IEA also predicts that renewable power additions will rebound next year to the level reached in 2019. This suggests that COVID-19’s impact on the clean energy transition is short term rather than long term.

“Nationwide lockdowns forced factories to temporarily shut their doors although many restrictions eased after the first few weeks as these industries were often deemed essential,” says Logan Goldie-Scot, head of clean power research at BloombergNEF. “Less robust parts of the value chain, often when activity was concentrated in a single region, were most affected.”

He cites Ecuador, which supplies 90 per cent of the world’s balsa wood, a key component used in wind turbine blades, as an example. “It had a strict lockdown, but this was lifted before lasting damage occurred,” says Goldie-Scot.

COVID can’t slow China’s growing dominance

China dominates the global supply of solar PV modules, as well as the raw materials for module assembly. Plants halted operations at the end of January, leading to equipment and material shortages and shipping delays.

However, production has now recovered, according to Dr Xiaojing Sun, senior analyst, solar systems and technologies, at Wood Mackenzie. “Overall, supply interruption was short lived and had limited impact on project timelines around the world,” she says.

Bottlenecks for some wind components, caused by a surge in demand in annual wind installations, were exacerbated by COVID-19, says Shashi Barla, principal analyst for global wind supply chain and technology, onshore and offshore, at Wood Mackenzie.

He adds that personnel movement and travel restrictions have, to an extent, impacted building projects in a few onshore markets, as well as the availability of service technicians for regular operations and maintenance.

Wood Mackenzie has therefore downgraded its global wind market outlook for 2020 by 6 gigawatts (GWs). “We anticipate further cuts to these forecasts in a few markets like India, though this will be largely offset by upgrades in China,” says Barla.

Renewable energy resilient through the crisis

In many respects, both the wind and solar industry have proved remarkably resilient during the COVID-19 crisis. Governments around the world understand the importance of continuing with projects that will support the global transition to renewable energy, says Rob Marsh, a partner at international law firm Norton Rose Fulbright and co-chair of the firm’s renewable energy practice.

“Within the realms of safety, most jurisdictions have gone as far as they possibly can to enable construction to continue and for supply chains to remain open and viable on an individual project basis,” he says. “So if you look across the market as a whole, the impact certainly has not been as marked as perhaps it has in other parts of the economy.”

It’s a reassuring assessment, but could government stimulus packages designed to shore up struggling economies in the wake of COVID-19 lead to further disruption of global supply chains? It wouldn’t be surprising if some countries were to attempt to reshore some clean energy manufacturing processes, but the results could be a mixed bag.

Most jurisdictions have gone as far as they possibly can to enable construction to continue and for supply chains to remain open

In January 2018, for example, the Trump administration introduced tariffs on US imports of solar cells and modules in an apparent effort to accelerate reshoring. US module manufacturing capacity rose as a result, but solar cell capacity didn’t.

“It [the tariff] provides a 2.5GW tariff-free quota for solar cells, which is not enough to meet all the newly built domestic module manufacturing’s demand,” says Wood Mackenzie’s Sun. “As a result, the module factories in the United States may have to pay tariffs to buy inputs into their modules, which drive up the domestic products’ prices.”

How tariffs could hamstring clean energy

A report by the Solar Energy Industries Association claims the tariffs will cost the United States $19 billion in investment and result in the loss of 62,000 jobs by 2021. In other words, tariffs are a blunt instrument that can have unforeseen effects on the domestic clean energy sector.

Goldie-Scot at BloombergNEF believes it will ultimately be impossible and inefficient to untangle global supply chains fully. But this still leaves room to reshore a lot of manufacturing, particularly where there are logical supply chain benefits.

“Manufacturing batteries near to demand for electric vehicles is logical as transporting millions of cells around the world is impractical and costly,” he says. Whereas: “Reshoring PV module manufacturing by contrast would make less sense and would distract from broader efforts to tackle climate change.”

According to GlobalData’s Das, many organisations are considering a hybrid framework for the supply chain, whereby a proportion of production and suppliers operate abroad, while some production and vendors are apportioned to the home country. “During a crisis, this combination provides the flexibility to maintain a balance in production depending on customer needs,” he says.

In fact, Marsh of Norton Rose Fulbright believes reshoring some of the supply chain and manufacturing processes for renewables could ultimately be a positive development. “These reshoring strategies are being delivered to further enable and boost the renewables economy in the relevant jurisdictions,” he says. “It would be quite a perverse outcome if that actually slowed down or increased the cost of deployment.”

Renewables such as wind and solar photovoltaics, or PV, now provide almost three tenths of global electricity. The industry’s spectacular growth ovder the past two decades has been supported by global supply chains that have helped to drive down costs. But the coronavirus pandemic threw an almighty spanner in the works, with border closures, lockdown restrictions and component delays slowing the progress of many clean energy projects.

“These ventures subsequently ran the risk of increased construction costs, as project developers tried to source parts from elsewhere,” says Somik Das, senior power analyst at GlobalData.

Quarantine measures also reduced the workforce on some construction sites, he adds, and contractors reliant on international labour were further impacted by travel restrictions.