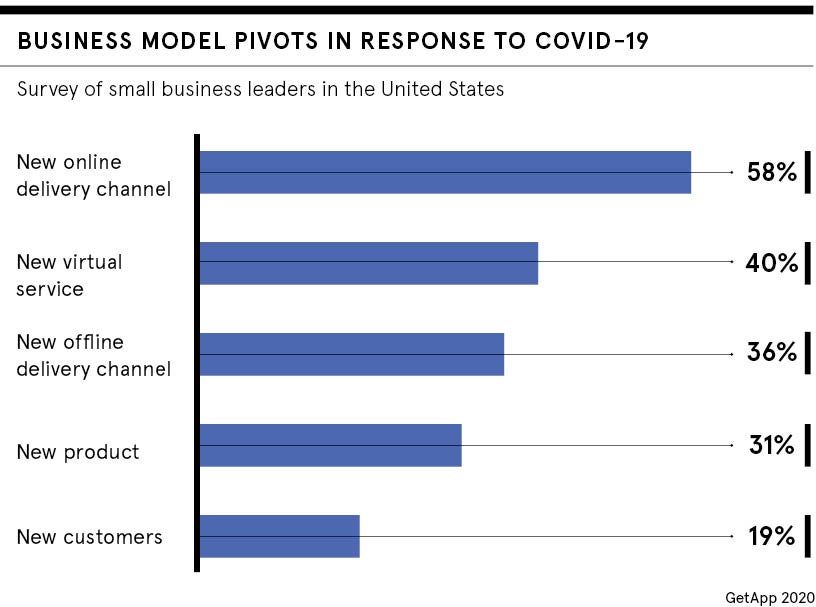

The most popular business growth strategy of 2020 is the pandemic pivot. According to a survey by software recommendation platform GetApp, 92 per cent of small businesses in the United States have decided to pivot business models since March, either setting up virtual services, launching new product lines or targeting a different customer base. When asked how their balance sheets were looking four months on, those that had pivoted were three times more likely to have boosted their incomes compared to those that didn’t.

The world has fundamentally changed since coronavirus sent shockwaves through the global economy in mid-March. As consumers’ priorities have adapted, businesses have had to keep up. But in such uncertain times, how can leaders know they’re making the right moves?

“It’s hard to know what the front foot looks like when you’re navigating so much uncertainty and no one knows how things are going to pan out in three, six, nine or twelve months,” says Kathryn Tingle, startup strategy lead and founder of Trailblazer Circles. “You need to be strategic and proactive as well as reactive; that’s a very fine balance to strike.”

The art of the successful pivot

It can be difficult to find a starting point when questioning the fundamental existence of your business model, but Tingle says it’s crucial to frame this as an opportunity to make positive changes and not see it as a setback. “I’m a firm believer that in dark times there’s usually a silver lining and in business that silver lining can be new opportunities,” she says. “All leaders knew the opportunities that digital transformation posed and during the pandemic there’s been a natural acceleration of these plans.”

You need to be strategic and proactive as well as reactive; that’s a very fine balance to strike

Tingle points to supermarket brand Sainsbury’s which, by pivoting to cloud technology, was able quickly to scale up its overloaded delivery service, a change that will pay dividends beyond the pandemic.

Emma Mills-Sheffield, who runs business consultancy Mindsetup, agrees changes to the business model should be made with longevity in mind where possible. “If it’s opportunistic, then you have to be really critical about whether you can plug that back into your core business growth strategy,” she says, citing examples of companies pivoting to produce personal protective equipment early on in the pandemic’s trajectory.

“Go back to your core purpose. Are these things fundamental to the business or bolt-ons to fill the gap for three months? You need to reflect and ask, ‘what do we stand for as a business and what do our customers need?’”

That’s not to say opportunistic pivots can’t be solid moves, particularly when relevant to the ecosystem a business sits within. When Bristol microdistillery Psychopomp decided to start producing hand sanitiser in March, it said it planned to sell the product at cost to restaurants and pubs.

It’s an attitude that Lee Powney, senior partner at innovation agency Vivaldi, says leaders should embrace when making fundamental strategic changes. “If you invert your strategic thinking to ask, ‘how can I create shared value?’, what you’re doing is reframing your business in a wider field, rather than just thinking of it in terms of creating products and services,” he explains.

If the business model ain’t broke

Not all business-model pivots need to be headline grabbing. Dr Vaughn Tan, lecturer at University College London’s School of Management and author of The Uncertainty Mindset, says simply acknowledging uncertainty can help leaders identify more subtle strategic shifts.

“That very basic assumption changes what you pay attention to strategically and it changes what you do internally: how you hire, how you motivate people and how you set goals,” he says. “With the uncertainty mindset, the idea is not that you conduct big tests with big consequences, but micro-tests that result in small course corrections along the way.”

However small or large the business model switch is, decisions should be grounded in data and solid insights, not just gut feeling. “The only way you can know if a pivot is likely to work is if you put down on paper all the assumptions you are making,” says Tan, emphasising the importance of crunching the numbers and comparing the cost of launching a new product or service with a realistic idea of how much revenue it will generate. Internal data can also provide hints on where changes need to be made.

“If you need to reinvest, be really clear about the outcomes you want to see,” Mills-Sheffield adds, noting that setting clear key performance indicators from the outset can prevent a situation where piles of cash continue to be invested, despite a pivot not bringing expected returns. “Go back to lean startup principles; what’s the minimum viable product?”

Finally, business owners should remember they’re not doing this alone and plenty of support can be leveraged by getting customers and employees on board with any strategic shifts being made.

“Whatever you decide to do, make sure you’re super clear on how you’ll communicate that with your staff, because they’re the ones on the journey with you,” Mills-Sheffield concludes. “It’s not just about pivoting from the top; it’s about making sure everybody’s on board.”

Shaking it up

Call the beautician

Mayfair salon Nails & Brows is renowned for creating neat, tidy, natural-looking brows and for telling clients not to mess about with them at home. During lockdown, founder Sherrille Riley decided to shift away from that advice and pivot the business model to teaching clients how to do their own touch-ups at home. The online consultation service lets clients book 15-minute video appointments when Riley talks them through the process of shaping, maintaining and applying makeup to their brows. The pivot has enabled Riley to expand her client base from London’s West End worldwide so now 50 per cent of her clients are in the United States.

Working from home is win-win

On Friday March 13, the Australian government announced a ban on gatherings of more than 500 people, exactly the sort Sydney-based Stagekings was in the business of building sets for. “That was 100 per cent of our upcoming work,” says founder Jeremy Fleming. With the right skills in-house to make anything out of timber, within a week Stagekings had gone from creating event stages to selling stand-up and regular desks to consumers under the name IsoKing. Demand for desks has been so strong that Fleming has been able to hire 17 additional members of staff and is now looking into licensing the brand in Europe.

Switching supply chain

Sales of children’s toy company PomPom’s indoor climbing frame peaked as the UK went into lockdown, but supply chain disruption in Europe made keeping up with demand difficult. In May, founder Katherine Rhodes set about designing an improved version of the product and sourcing a UK supplier to make it for her. It was a leap of faith as this was the first time PomPom had designed its own product and all dealings with the manufacturer have been done over the phone or Skype. But it has paid off. When the new model launched in September, it sold out within a fortnight.

Child’s play online

In 2018, Delvene Pitt launched Littlecrowns Storyhouse, a sensory playgroup for toddlers. In March, Pitt not only shifted her sessions online, but decided to add a new dimension to the business: “I thought, why don’t I use my production degree and start putting on a kids show?” Investing £3,000 in new equipment, such as editing software and lighting, Pitt began uploading a weekly children’s puppet show to YouTube alongside her private Zoom sessions. The business-model pivot has enabled her to reach new customers, including schools, and expand her audience. In 2021, Pitt plans to launch a membership model giving parents access to additional educational content.

DIY dinners

With their restaurant shuttered, chefs Zijun Meng and Ana Gonçalves, founders of Tōu, decided to turn their customers into cooks. In August, they launched a meal kit containing everything to make Tōu’s iconic Iberico pork katsu sando at home for £10.50. “When we were open as a restaurant, we were doing 500 of those sandwiches per week, now we’re doing about 50 or 60,” says Gonçalves. “It’s enough for us to keep the brand surviving.” The restaurant remains closed and the plan is to keep building out the at-home offering, with delivery planned to go nationwide at the start of 2021.

Cash-flow conundrum

India’s nationwide lockdown meant US direct-to-consumer spice brand Diaspora Co had no idea when it would be able to get hold of its raw ingredients. With supplies dwindling and a need to pay its farm partners to keep them in business, founder Sana Javeri Kadri decided to overhaul the company’s cash-flow strategy, switching to a pre-sale model. “Pre-orders were such a success that we ended up buying 35 per cent more than we had forecast for the year, just to keep up with demand,” she says. Since making the switch, Diaspora Co has raised more than $750,000 from 13,500 pre-sale orders, far in excess of the 4,000 orders it expected.

Work out wherever

So customers could work out from the comfort of their own homes, Urban Sports Club, which sells multi-access passes to fitness venues across Europe, teamed up with Cologne-based software company Fitogram to enable its gym partners to run sessions online. Studios have uploaded more than 160,000 classes to the platform since mid-March. “Our studios are now in hybrid mode,” says Franka Schuster, Urban Sports Club’s public relations lead. “Our French colleagues are switching back to online because of the new lockdown, but in Berlin we are still training outside, inside and with the livestreams.”

From rentals to restaurants

In March, US universities shifted their teaching online, leaving LoftSmart, a platform that helped college students find accommodation, without a market. Founder Sam Bernstein decided to overhaul the operation, building an entirely new platform that let restaurants deliver cooking classes and subscription offerings online. Table22 has so far onboarded restaurants in 13 US cities, which have generated more than $500,000 in revenues between them; Table22 takes a cut of each subscription sold. “I don’t see us going back,” Bernstein reflects. “I’m much more passionate about the market we’re solving problems for now and I want to keep working on that.”

The most popular business growth strategy of 2020 is the pandemic pivot. According to a survey by software recommendation platform GetApp, 92 per cent of small businesses in the United States have decided to pivot business models since March, either setting up virtual services, launching new product lines or targeting a different customer base. When asked how their balance sheets were looking four months on, those that had pivoted were three times more likely to have boosted their incomes compared to those that didn’t.

The world has fundamentally changed since coronavirus sent shockwaves through the global economy in mid-March. As consumers’ priorities have adapted, businesses have had to keep up. But in such uncertain times, how can leaders know they’re making the right moves?