When it costs an eye-watering £1 billion to bring a major drug to market, it is easy to understand how protecting that investment becomes a prime focus.

Pharmaceutical companies are staffed by ranks of attorneys, and the intellectual property (IP) specialist is now a pivotal position in the research and development (R&D) cycle that keeps a company profitable and new drugs flowing to patients.

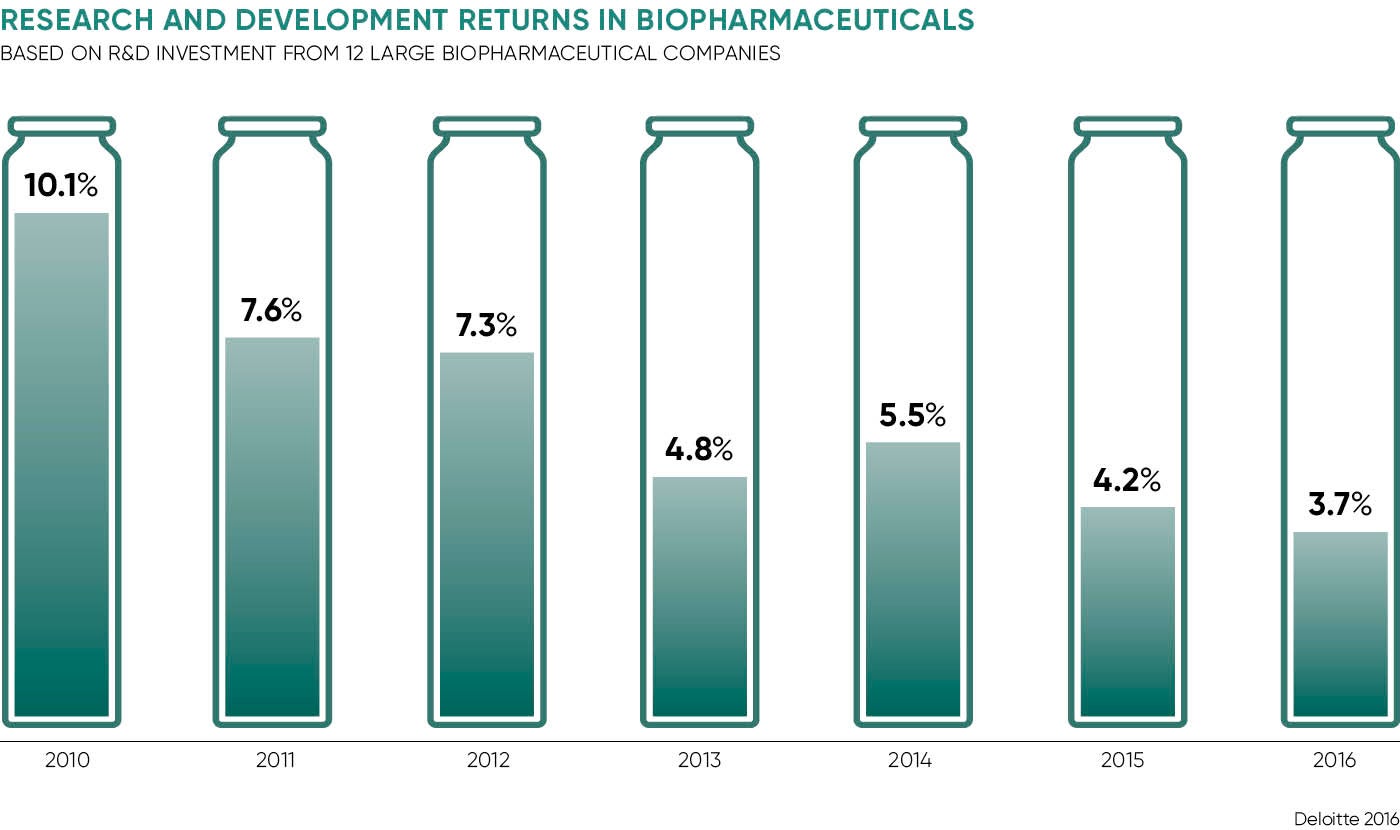

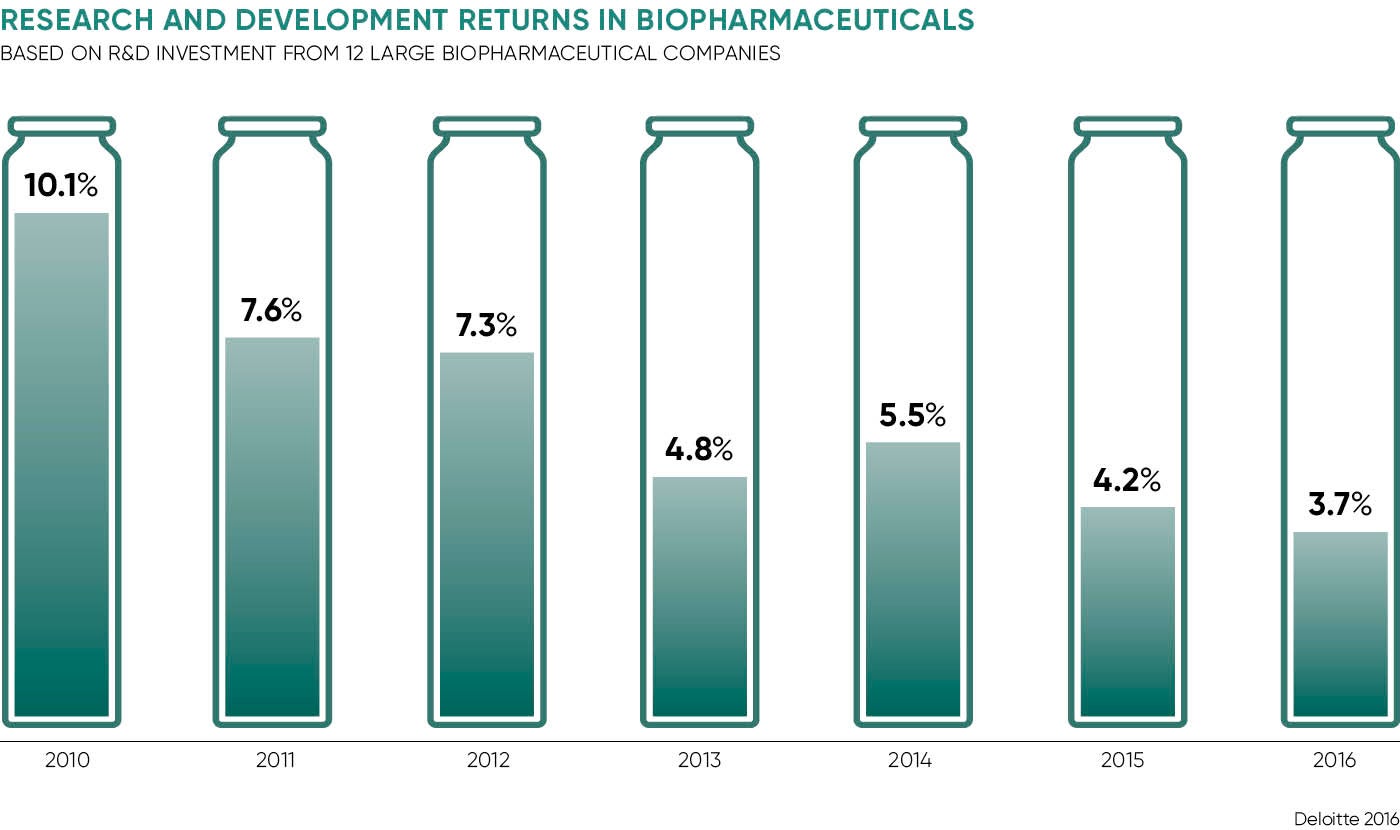

Tighter regulatory frameworks and even tighter purse strings controlled by healthcare systems are putting the squeeze on pharma returns and limiting R&D budgets. Figures from analysts Deloitte in 2016 reported projected return on investment was at a six-year low while development costs had risen by almost a third.

The litany of market changes is vexing for the industry. The generation of blockbuster drugs, with massive returns, has ended, national healthcare budgets are receding, traditional management methods are being challenged and new players, such as electronics and software companies, are entering the arena.

“For pharmaceutical companies, the patent system is its lifeblood and it simply wouldn’t survive without it,” says Simon Wright, a patent attorney with J A Kemp and chairman of the Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys’ life sciences committee. “The cost of getting a product to market is high and there is a high failure rate, so you are not going to get investment unless you can protect your product and innovation. Quite frankly, it would all collapse without good IP.”

How it works

Companies get 20 years’ patent protection, but the clock starts ticking from the moment a product details are filed. It can take up to 15 years to reach a market launch although a supplementary protection certificate, extending exclusivity by up to five years, can be obtained.

But once that patent expires, other companies can start selling generic copies of a drug, often at discounted rates as they have not had to make the initial discovery outlay, so a lucrative market can disappear quickly.

The stakes are high and AbbVie is fighting on multiple fronts to protect its blockbuster arthritis drug Humira, which generated $14 billion revenue in 2016, from generic alternatives as its initial patent expires.

Quite frankly, it would all collapse without good IP

Further battles are also expected along with test cases over who owns the IP to patient data across healthcare and lifestyle sectors. In March, for example, adidas filed a lawsuit against sport shoe maker Asics over wearable fitness tracker technology rights, claiming ten IP patents had been infringed.

Susie Middlemiss, partner and head of the intellectual property practice at law firm Slaughter and May, which acts for major pharma firms, sees an “exciting and expanding world” of healthcare IP.

“IP is growing everywhere, including healthcare, and it is an increasingly competitive landscape with more diverse companies involved,” she says. “There is a huge amount of data being used in healthcare and in the NHS to model patient care, and that is all underpinned by IP.

“If there wasn’t IP, then companies would start to work in secret on products that couldn’t be reverse engineered and areas where secrecy couldn’t be maintained would be neglected. A company needs that monopoly period to recoup its investment to ensure it can continue with its R&D programmes.”

New challenges

The profile of pharma business has been changing over the last 20 years with niche startups, specialist genetic companies and spin-offs from academic institutions generating a large proportion of the innovation and discovery work that was once contained in-house. With new fields such as electronics and computer software driving medical devices and data collection, the IP field has become complex.

“IP has become harder to pin down,” adds Ms Middlemiss. “In the old days, the pharma company would simply buy a product or the company, but those companies are now hanging on to their IP and licensing it to the bigger companies which requires a lot more structuring to deals.”

The challenges presented by new technologies to healthcare IP and licensing was a featured topic at the recent Licensing Executives Society International Conference in Paris, attended by members from 33 national societies and leading figures from industry.

IP in healthcare is growing steadily with the government’s Intellectual Property Office, which manages patents, trademarks and copyright, reporting that healthcare patents in the UK had risen from 1,098 in 2011 to 1,358 in 2015.

A prime example of IP working to the advantage of healthcare was highlighted when British pharma giant GSK joined forces with Google’s life sciences vehicle Verily to develop and commercialise implantable devices that can modulate electronic signals along nerves in the body to treat some chronic conditions. The joint venture, known as Galvani Bioelectronics, creates synergy between GSK’s pharma traditions and the disruptive influence of electronics.

So many industry experts believe IP is the key to a successful company as it is a powerful tool for R&D, as well as revenue generation, allowing non-core products to be licensed out to fund other research. It is even more important for the myriad of startups populating healthcare that need pay as much attention to IP to protect their assets as they do to innovation and discovery.