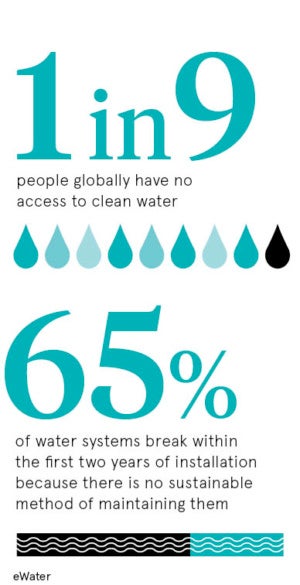

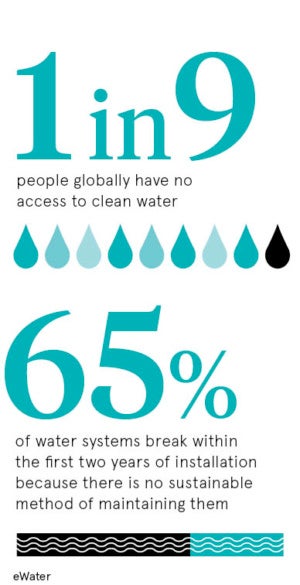

Water is fundamental, whether for drinking, supporting agriculture and livestock, energy or industry, in both developed and developing economies. But 783 million people, one in nine of the world’s population, have no access to clean water.

A key challenge, of course, is how to pay for water although, in the UK, privatisation has covered the cost of major investments in infrastructure. According to Ian Gray, global water asset management lead at Arup, £120 billion has been invested in the UK water sector since privatisation.

Historically, however, water has been managed in a fragmented way, which must change through more effective management, says Mr Gray. “We’ve started to talk about resilience – the way we manage extremes; how we respond to stresses and shocks on the system,” he says.

Historically, however, water has been managed in a fragmented way, which must change through more effective management, says Mr Gray. “We’ve started to talk about resilience – the way we manage extremes; how we respond to stresses and shocks on the system,” he says.

Many operators are beginning to work together, recognising the interdependence which comes from having many players in a supply chain, especially one that ultimately cannot be controlled.

Part of the challenge lies in customer expectations. Bryan Harvey, vice president for utilities in Europe at Jacobs, points out that while oil may sell for around $60 a barrel, water is priced at about $1 a barrel. There are no natural competitors to water providers and even privatised water operators are heavily regulated.

Mamadou Dia, president of AquaFed, says: “There is no real reason to oppose public versus private models, and it is much more interesting to look at institutional models that are enablers for different types of co-operation. The most important thing is that it is clear who has to deliver on what types of responsibilities, so constant improvement in performance is achieved for the benefit of the end-users.”

The lesson to be learnt for emerging markets must be to monitor and maintain physical assets to avoid future replacement legacies

In the UK, more than 20 per cent of abstracted and treated water is lost from leaking mains. Many of these date from the Victorian era, while in Japan key water mains are relined every ten years. Dr Phil Aldous, of Thomson Ecology, says: “Replacing network infrastructure is not just expensive financially. The other costs of congestion and pollution make the task a multi-disciplinary challenge. The lesson to be learnt for emerging markets must be to monitor and maintain physical assets to avoid future replacement legacies.”

This can be enabled by the implementation of smart technology linking sensors and collating data to ensure smooth management for the financial controller, operator and asset owner. Bill Clee, chief executive and founder of Asset Mapping, says smart technology enables robust and valid data to be shared across the value chain. “We have an infrastructure that isn’t monitoring itself and reporting problems,” he says, calling for a more holistic management of resources and services.

Dr Aldous stresses the importance of a strong regulatory regime. “Without a legal regime, the danger is that water authorities control the water resource, and focus on profits and meeting growth, at the expense of environmental sustainability. In Pakistan’s Punjab, for example, over-pumping is lowering the water table by half a metre a year, threatening food and water security and making thirsty crops such as rice much harder to grow.

In emerging markets, new technologies are offering an entirely new way to develop and deploy water services. In China, India and Africa there is the potential to replicate the leap made in telephony, without having to manage legacy infrastructure

This is especially true in rural areas, where there may not be sufficient people to justify major investment by any single utility. Mohsen Mohseninia, vice president of market development in Europe at Aeris, which works with Lorenz in delivering remote water management, warns: “Creating infrastructure that delivers water to these areas and then subsequently monitoring and maintaining this infrastructure can be an incredibly time-consuming and expensive operation.”

Paul Marshall, chief customer officer and co-founder of Eseye, says one of the most difficult aspects of deploying water pumps, for example, is that without the skills to maintain them around 65 per cent break within the first two years. The solution, implemented by partner eWaterPay, “closed the circle around both the water cycle and the cash flow”, says Mr Marshall.

This solution uses three technologies – mobile money, the internet of things and near-field communication – to manage the provision of clean, low-cost water, accessible 24/7. While installing solar-powered pumps, filtration systems, tanks and taps, local engineers are trained to maintain and upgrade the system. This includes replacing hand pumps or leaky, unreliable outlets with a smartcard reader, communications hub and solar-powered electronic valve.

The system can be shared between families, and water can be measured and paid for. So far 13,000 people have constant access to clean water and provision is forecast to increase for up to ten million more people over the next five years through instillation of 100,000 more taps.

As always there is an issue with affordability. Calculations suggest that using this system will cost $2.50 a person each year, for a minimum amount of clean water. However, Mr Marshall points out that locals have always paid for water, but in different ways, either with their time, walking long distances, with their health, through drinking unclean water, or with education, by making children collect water instead of sending them to school.