When sanctions were imposed on Russia, banks in the UK, elsewhere in the European Union and in the United States became responsible for keeping sanctioned firms, government bodies and individuals outside the banking system. Having the wrong customer can cost a bank much money.

In 2012, HSBC was fined $1.9 billion by US authorities to settle charges relating to laundering Mexican drug cartel money. In 2014, French bank BNP Paribas was fined almost $9 billion by American prosecutors for processing payments that broke US sanctions on Cuba, Iran and Sudan. Standard Chartered was fined $300 million in 2014 for failing to remediate anti-money laundering problems for which it had been fined $340 million in 2012, related to sanctions on Iran.

Anti-money laundering or AML covers drug trafficking, corruption, tax fraud and human trafficking, among other criminal activity. Big fines are not even the greatest threat. If a government decides to ban an offending bank from clearing transactions in that country’s currency, it can cripple a firm’s ability to trade internationally. The US has issued partial bans on clearing dollars before. Given the existential threat this poses to parts of their businesses, going against AML and know-your-customer (KYC) rules is not a good choice.

Know your customer

Steve Goldstein, chief executive of Alacra, a firm that supports banks in complying with regulations, says some with substandard processes do not have remedial programmes in place, despite the value that a single view of the customer offers.

“When things change with a client – if the client moves or decides to do business in a new jurisdiction – and that information is not held within the bank, then the bank doesn’t really know its customer,” he says. “Consequently, the single view of a customer is gaining traction as it also feeds into giving the bank a single view of the customer’s credit exposures.”

Putting together a single picture of a customer is difficult and proving the identity of a new client is equally challenging

For big sprawling banks, working in multiple countries and with many different divisions and businesses, it is hard to maintain a single view and standard of operation. This is exacerbated by the complexity of the clients that banks deal with.

But banks are not the only businesses through which illicit money can be channelled. In 2015, a report by anti-corruption campaign group Transparency International found that at least £180-million-worth of properties in the UK had been brought under criminal investigation as the suspected proceeds of corruption since 2004. However, banks are the target for regulators.

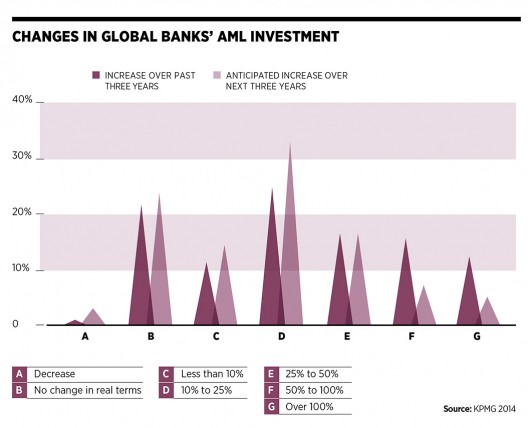

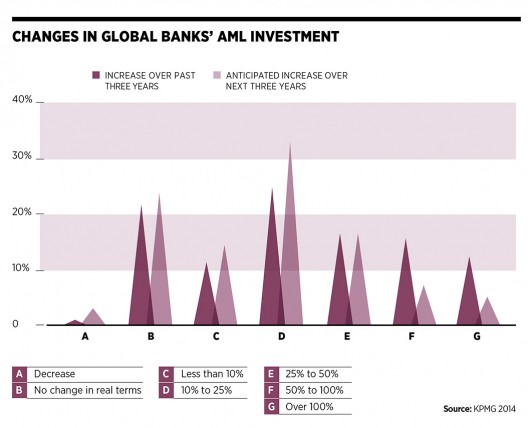

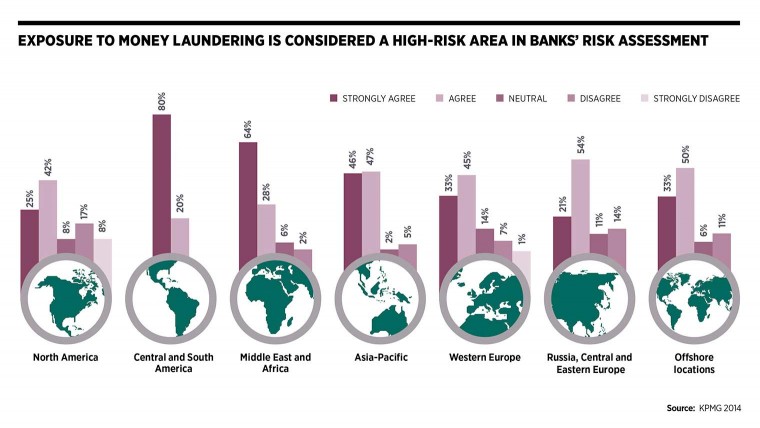

[infographic]

Banks carry responsibility

John Cusack, global head, financial crime compliance, and group money laundering reporting officer at Standard Chartered, says: “There are no other organisations in the private sector that contribute as much to the fight against financial crime as banks. Many other organisations that could have regulations applied to them do not and so banks carry a huge amount of responsibility. When we get it badly wrong, we get punished for that and, while we should be held to the standards required, I do think that our contribution should also be recognised.”

A huge range of crimes, political judgments and regulations can determine whether or not an entity or customer should be allowed to use a bank. KYC and AML rules set a standard for identifying criminals or politically sensitive individuals so that the bank can prevent them from using the banking system to process money from criminal or corrupt sources. But it is not only individuals who are of concern, companies and government entities, along with firms associated with countries subject to sanctions, all have to be spotted. Yet putting together a single picture of a customer is difficult and proving the identity of a new client is equally challenging.

[embed_related]

Jon May, chief executive of kyc.com, says: “Large firms have lots of subsidiaries with different names, so you might think you are dealing with fund manager Blackrock, but is it Blackrock US or Blackrock Europe? How do you know exactly who you are dealing with? That information is then distributed across a number of different databases in a bank, not all of which will talk to each other, and different divisions will probably have a number of different databases.”

Tracking data

If data is not coherent or consistent, then the bank’s ability to screen potential clients is impaired. Recent research by financial crime prevention specialists NICE Actimize shows that 30 per cent of financial institutions surveyed found data quality and availability was a major problem in their KYC programmes, followed by the use of manual processes and maintenance of existing IT infrastructure. The lack of standardisation in terms of document collection and submission has long been a challenge for firms, increasing their risk and costs.

Paul Taylor, director of compliance services at interbank messaging network SWIFT, says: “Banks that have very well-connected and simplified systemic and hierarchical architectures will not face the same challenge as ones who do not. Smaller banks do not necessarily have the investment profile in terms of headcount, operational tools or systems compared with larger banks, and they often need to deal with a magnitude of requests for different sets of information at different times, creating resource issues and inefficiencies.”

The structural challenge that exists within firms can also be seen between banks; sharing information between firms is difficult from a legal and operational perspective. Consequently, a new model has sprung up that allows banks to deal with a centralised hub to store and validate data provided.

“The emergence of KYC utility models over the recent past has sought to mutualise the cost of individual data and document collection, in some instances even seeking to standardise the approach and documentation required,” says Mr Taylor.

In 2014, four new utility platforms were launched, run by SWIFT, Markit, US trade processing and clearing firm DTCC, and market data provider Thomson Reuters. Offering a range of centralised hubs, designed to alleviate the fragmentation of data within firms and between firms, they also standardise the data that firms need to ensure the right checks are being run in compliance with the most up-to-date rules. They tackle two of the big challenges banks face – the number of data sources needed to validate potential customers and the pace of change.

In the NICE Actimize survey, 30 per cent of institutions report using between four and six external data sources to augment existing customers’ information, with 27 per cent of institutions using more than seven sources. Also, recent regulatory updates have impacted the approach to KYC of 61 per cent of financial institutions.

Mr Cusack says: “The standards are continuously revised to push them ever higher. Keeping on top of that continuous evolution is the number-one challenge for banks and it is unlikely to ever reverse.”

Both Mr May and Mr Taylor acknowledge their firms’ offerings are not a panacea for banks. However, they point out they are unencumbered by the legacy technology and practices that many banks have, often through the acquisition of smaller banks, which gives their firms greater flexibility to meet new requirements.

“We have an advantage in terms of a fresh infrastructure,” says Mr May. “Our firm’s heritage is in the information data space, so we are very familiar with bringing data feeds together and using those to coalesce a picture of an entity.”

Taking advantage of new operational models could lift the burden for firms who are unlikely to find the pressure from authorities lifting any time soon.

Alacra’s Mr Goldstein concludes: “Regulators see this as an opportunity to acquire money. They have been successful in the past; they are always looking for more money, so I suspect they are not going to stop looking.”

Know your customer

Banks carry responsibility