Although department stores are having a hard time on the high street, their online equivalent, the marketplace, is going from strength to strength. Whether it’s Asos in fashion, Wayfair in furnishings or Amazon just about everywhere, a marketplace that puts many brands under one roof will attract far more traffic than one retailer’s store could ever do. With the right listing and price, a brand can shift a lot of units on these sites.

The obvious downside is that a marketplace will take a cut of anywhere between 10% and 30% on each sale. But the retailer will also have little control over how their brand is presented by a third-party site, which could be recommending complementary purchases from a competitor, for instance. And, crucially, the customer relationship is owned by the marketplace, no one else.

We have sold direct to consumers since then, but it’s marketplaces that have given us reach

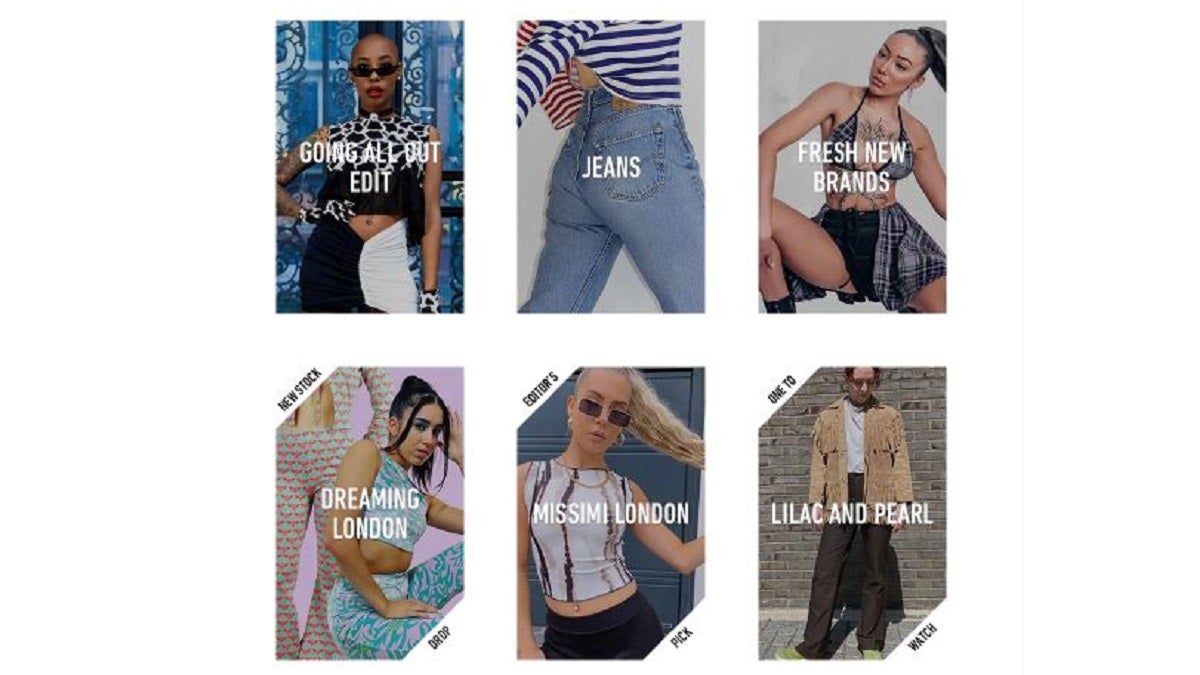

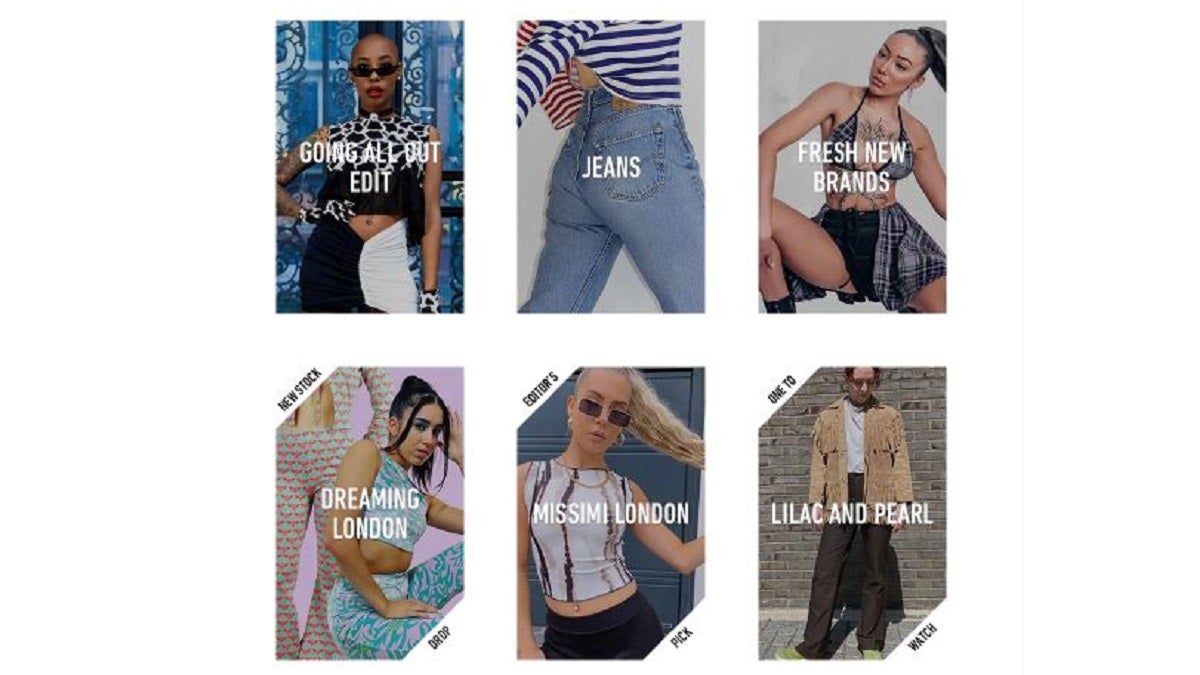

These caveats don’t seem to be much of a deterrent. The head of marketplace and men’s brands at Asos, Jo Hunt, reveals that it had 20 sellers when it opened for business in 2010. Today, it has 1,300 – more than 500 of which have joined in the past year alone.

She believes that the real allure of a marketplace lies in the ability it gives customers to shop in many boutiques with the backing of a well-known brand.

“Our customers are often looking for something unique or for a one-off piece. The platform enables them to seek out special pieces from our global community with the added benefit of Asos curation and customer experience,” Hunt says.

Marketplaces offer reach

For many retail entrepreneurs, particularly those just establishing themselves, the promise of a sales boost outweighs any concerns about giving up control. When Richard Levin set up Loop Cashmere in November 2020 without a single customer on his database, he needed to choose a third party through which his business could grow at speed. His first choice was Wolf & Badger, a marketplace specialising in sustainable products.

“We have sold direct to consumers since then, but it’s marketplaces that have given us reach,” Levin says. “There’s also the issue when you’re just starting that people don’t know if they can trust you. They’ve not heard of you before, so they’re far more likely to spend a few hundred pounds on cashmere through a marketplace, where they know they’re protected, than from a site that isn’t so familiar.”

What if a marketplace is a retailer too?

Some entrepreneurs who are thinking about selling via a marketplace worry that it might obtain too much information about their businesses. According to Cas Paton, founder and MD of the OnBuy marketplace, this could be an issue if the marketplace is a retailer in its own right. The concern is that a “cat and mouse” situation would arise, whereby a new product’s successful debut on that marketplace prompts the marketplace to start selling a rival product.

It’s not a possibility that concerns Paul Simpson, co-owner and sales director of kitchen appliances brand Swan Products. He believes that marketplaces are no different in this respect from high-street stores, which often sell own-brand goods. The benefits they offer, he adds, outweigh any of the risks.

“In traditional retail, you’re reliant on a buyer to say whether they like something or not. If they do, you might get a few items on sale,” Simpson says. “A marketplace offers you a website with lots of traffic where you can show off all your goods. It really works for us to get different products in the full range of colours on one site. Our hope is that people like our products and then return to the marketplace and search for our name when they’re next making a purchase.”

Sales never come for free

Entrepreneurs need to stop worrying about ceding too much money and control to a marketplace – otherwise, they risk losing sales, argues Andrew Banks. He not only runs an ecommerce consultancy, VentureForge, but also puts his money where his mouth is in co-owning a skincare brand, VeloSkin, that’s sold both D2C and through Amazon.

“There is a cost to generating each sale, whether it’s on marketing to pull someone to your own website or on giving the marketplace a cut,” he says. “What you have to consider is that a marketplace does this far more cost-effectively than a small business would be able to.”

Banks continues: “In VeloSkin’s case, we sell on a fulfilled-by-Amazon basis, so it ships our orders under the Prime banner. It’s my top advice for other merchants. If you get your promotions and prices right, the marketplace can generate a huge amount of sales and fulfil those orders at far less cost than you can do for yourself.”

Why sell to, not through, a marketplace

Some marketplaces go beyond third-party selling and invite businesses to work more closely with them. Using Amazon’s terms, this is changing your status from a third-party ‘seller’ to a ‘vendor’. Under this closer arrangement, the marketplace buys stock from the retailer, which it then sells itself. Rather than selling through the marketplace, the retailer is selling to the marketplace.

There are usually upsides and downsides to any type of relationship with a marketplace. Operating as a vendor is no exception to this, as Anushi Desai, co-founder of vegan snack brand Plant Pops, explains.

“Selling to Amazon is great, because you get large purchase orders that you can send all in one batch,” she says. “It’s a reliable source of high-volume sales, which is similar to what you’d have when dealing with other wholesalers. The downsides are that you have no control over the price and there’s a lot of stock with someone else – on payment terms of 90 days – instead of in your own warehouse, which you could be using to fulfil other orders.”

Marketplaces can help you be everywhere

For many retail brands, the rise of the marketplace has come at a time when they’re under mounting pressure to be available wherever their customers want to do their shopping. Callum Campbell, CEO of commerce platform Linnworks, advises entrepreneurs to think a little less about controlling the relationship with their customers and instead focus on where those people are spending most of their time online.

“By using their own websites to sell directly to consumers, retailers can personalise the experience and own that relationship,” he says. “But, to truly grow, they need to go and meet potential customers where they are, which includes marketplaces and, increasingly, social media.”

Although department stores are having a hard time on the high street, their online equivalent, the marketplace, is going from strength to strength. Whether it’s Asos in fashion, Wayfair in furnishings or Amazon just about everywhere, a marketplace that puts many brands under one roof will attract far more traffic than one retailer’s store could ever do. With the right listing and price, a brand can shift a lot of units on these sites.

The obvious downside is that a marketplace will take a cut of anywhere between 10% and 30% on each sale. But the retailer will also have little control over how their brand is presented by a third-party site, which could be recommending complementary purchases from a competitor, for instance. And, crucially, the customer relationship is owned by the marketplace, no one else.

We have sold direct to consumers since then, but it’s marketplaces that have given us reach