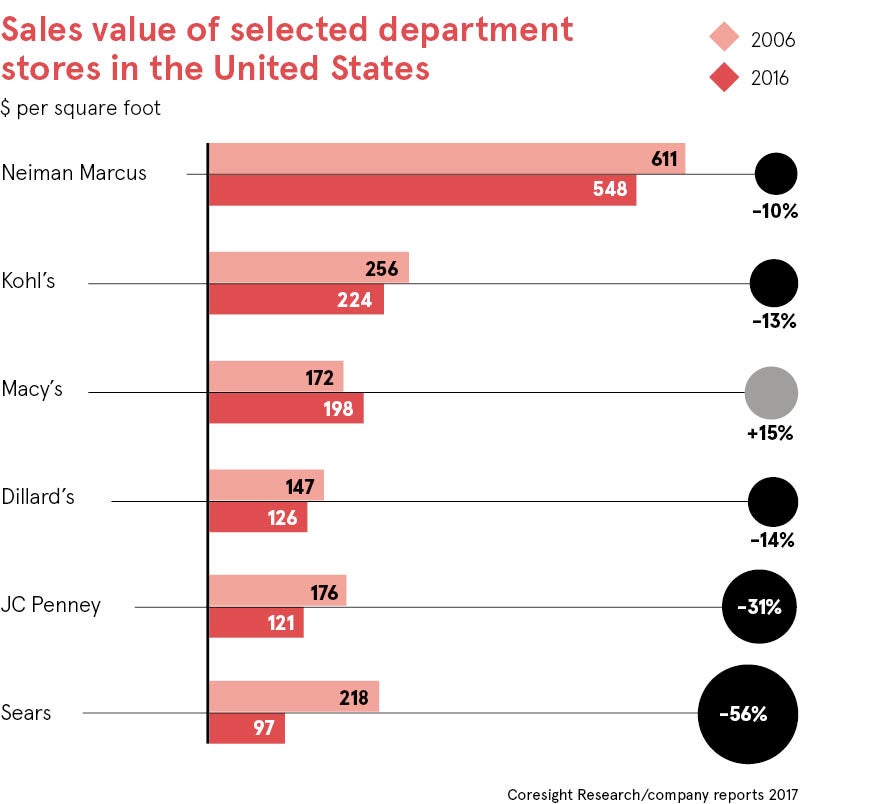

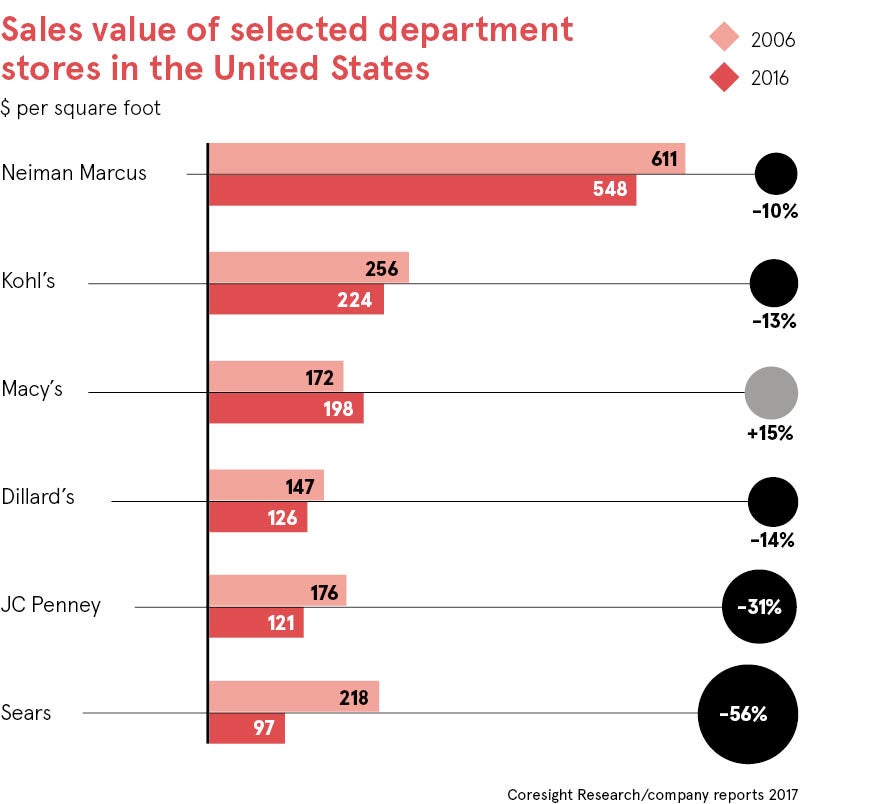

For many traditional department stores, 2017 was not a good year. In the United States, J.C. Penney closed 138 branches and Sears shuttered a reported total of 300 stores. In the UK, Debenhams announced that ten of its 176 locations would close unless they improve.

“A department store is a legacy format. It used to be the new kid in town 100 years ago, but now it’s finding it difficult,” says Tony Shiret, UK general retail analyst at Whitman Howard.

The problems faced by department stores are myriad. Less efficient than specialist shops and losing market share to discount stores, their previously defining feature – an extensive product range – has been usurped by the likes of Amazon.

As of January 2018, 16.5 per cent of all retail sales in the UK were made online, an increase of 9.1 per cent year on year, yet many department stores have been slow to move online, with lacklustre websites and poor online browsing experiences.

But all is not lost for while experts agree there will be fewer department stores in the future, those willing to find new ways to fit into the lives of their customers can succeed.

“Long term, the format and what they sell will have to be adapted. It’s too much nondescript, overlapping type of product and not enough destination product in these shops,” says Mr Shiret.

Stores such as John Lewis and Harrods will be successful over the next ten years because they have a clear strategy, identity and the consumer knows what they stand for, says Dr Jeff Bray, principal academic in marketing and consumer behaviour at Bournemouth University.

“If you asked consumers to name department stores they’d say Debenhams and House of Fraser, but they’d class John Lewis as a family friend. It’s seen or felt to be different and more ethical, partly because of its ownership structure,” he says.

John Lewis has previously found its online sales increase in areas where it opens a new store, and is one of the UK’s leading online retailers when ranked by online sales and traffic to its website. The store embraced mobile shopping quicker than competitors and its site design is focused on making it as easy as possible to find and purchase products.

“The future success of department stores lies in them offering great service in an omnichannel way. John Lewis’s service proposition is not diluted by shopping online or offline,” says Hugh Fletcher, global head of consultancy and innovation at digital commerce consultancy Salmon.

The department store of the future will need to be more specialised and offer an alternative to online marketplaces. He adds: “What Amazon really can’t do is the human element. A big differentiator is the ability to have products installed, set up and disposed of by trained personnel.”

Department stores can carve out a niche if they position themselves as a solution to a problem rather than the provider of a product

Housing a carefully curated range of products under one roof, as John Lewis does, coupled with more specialist in-store services, such as wardrobe makeovers or an interior design consultancy, would offer consumers something they cannot get online and turn a physical presence into a competitive advantage.

“Department stores can carve out a niche if they position themselves as a solution to a problem rather than the provider of a product,” says Dr Bray. Such assisted shopping could evolve into a department store as concierge service with loyal shoppers assigned a regular member of staff, he adds.

Building on their human element is crucial to department stores’ success, says Mr Fletcher. “Take John Lewis’s baby section. The consumer is faced with going online to buy a product, versus going in-store to see an expert who has been trained in the products,” he says. “While live chat and video services have been set up to do this, human face to face still dominates.”

The future department store should offer customers tactility through a physical store and a great way to browse products online before they come in, such as a limitless stock option allowing them to view a product in any size or colour, says Craig Phillipson, managing director of retail design consultancy Shopworks.

“If everyone can find out about everything on the internet and order it to their home, department stores need to deliver something more interesting, whether that’s customer service, instant gratification or personalisation,” he says.

The cost of maintaining such large spaces is high and it’s difficult to offload massive, multi-floor properties, but the “local” experiments of brands such as Nordstrom could offer a solution, Mr Phillipson adds. At a fraction of the size of their other stores, these local outlets are centrally located with no inventory and offer customers a more convenient way to browse products and collect ordered items.

Whether through smaller, local versions or by placing counters in other conveniently located partner stores, a much greater investment in click-and-collect services would make department stores more efficient options for consumers. In the future, facial recognition or geolocation technology could alert stores to a customer’s approach so their goods are ready for collection on arrival.

The cost of such technology or reinvention may be seen as prohibitive by some brands, but those that use it to fit their customers’ lives will find success. For too long department stores have been on the back foot as online marketplaces changed consumer habits and their market share.

While they would like to replicate Amazon’s success, to do so they must differentiate themselves through a relentless focus on the consumer and by turning their physical presence from albatross to advantage.