Massive inflows of private equity have resulted in a record amount of unused capital – and there is no immediate sign that enough opportunities for investment are going to arise.

As Bain Capital partner Graham Elton says: “It’s very much a seller’s market” and this is likely to have consequences for mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

As private equity managers receive more cash from pension funds and endowments, they are coming under pressure from those same investors to put the cash to work. As a result, sellers – whether company boards or other private equity owners – find they can demand higher prices.

Meanwhile, in the public arena, a multi-year bull market has pushed prices to record levels. The S&P 500 Index recorded its highest-ever closing price on May 21, driven in part by quantitative easing on both sides of the Atlantic. This means initial public offerings (IPOs) have also been an attractive exit strategy for several years.

IPOs pose their own problems by generating more cash that sellers will then be under pressure to recycle as soon as possible.

However, there are some signals of weakness. Duff & Phelps head of corporate finance Robert Bartell notes that some debt deals linked to private equity have been pulled recently in order for money to be reallocated elsewhere – something “we haven’t seen for four years”, he says.

In November, Bloomberg reported that Bank of America and Morgan Stanley had abandoned a debt package backing a proposed $5.5-billion (£3.6-billion) transaction for Carlyle Group. With the US Federal Reserve seeming poised to raise interest rates for the first time since 2006, borrowing to buy is likely to become less attractive, even if the base rate only rises marginally.

According to Howard Marks, co-founder of specialist credit investment firm Oaktree Capital: “When people are afraid of being left behind and afraid of not getting a deal – fear of missing out – then the market is not a strict disciplinarian. When they balance that with fear of losing money, then the market is much healthier.”

Public company acquirers are looking to strategic acquisitions to drive revenue synergies, product expansion and cost reductions

Private equity exits

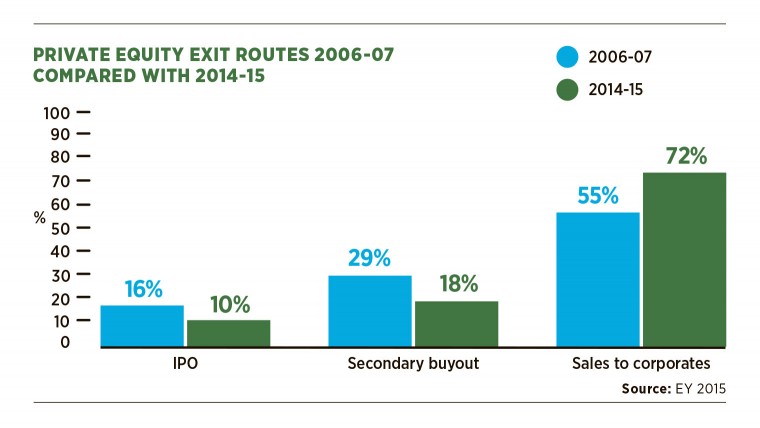

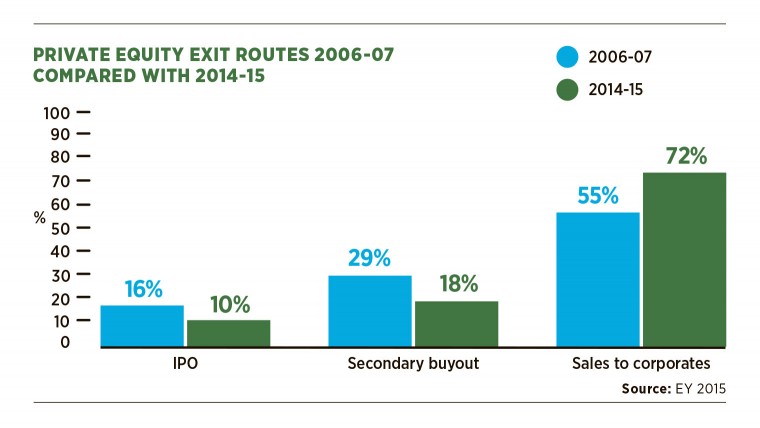

Elsewhere, EY’s private equity IPO data show that $38.5 billion was raised in the first nine months of 2015 by private equity funds in 120 listings. This compares with 163 IPOs raising $95.8 billion during the same period in 2014.

IPOs may have declined, but selling to other private equity funds or to acquiring corporates has remained strong, with 625 companies sold through M&A with a total value of roughly $262 billion, roughly in line with last year. In Mr Bartell’s view, doing business with corporates is “still a home run for sellers”.

There is definitely downside risk, but it would be described as modest, maybe a 5 to 10 per cent correction

“Private equity buyers are becoming a little more cautious and discerning,” he adds, “but public company acquirers face anaemic organic growth and are looking to strategic acquisitions to drive revenue synergies, product expansion and cost reductions.”

Bain Capital’s Mr Elton argues that the tension between high prices and excess cash has to unwind soon. “The rate at which things are being sold could slow – that would effectively be a built-in correction,” he says. “There has to be some form of price correction to enable more money to be put to work.”

Mr Elton speculates that some private equity firms may delay exits from companies purchased during the pre-crisis market highs of 2006 and 2007 to give more time to recoup the money spent. The effects could materialise from 2016 as 2006-vintage funds reach the end of their typical decade-long investment cycle.

Downside risk

“There is enough uncertainty that private equity funds are pretty cautious about what they do,” Mr Bartell says. “The view is that while there could be a correction in 2016, it’s unlikely to be a fall of 30 to 40 per cent. When you talk to wealth managers, they say there is definitely downside risk, but it would be described as modest, maybe a 5 to 10 per cent correction.”

This still leaves the problem of excess capital. In a recent report from PitchBook into the European middle-market – private equity deals worth between €25 million and €1 billion (£17.6 million and £703 million) – the authors noted a surge in the value of deals involving consumer-facing companies to 34.6 per cent of the industry’s total deal value at the end of the third quarter.

This still leaves the problem of excess capital. In a recent report from PitchBook into the European middle-market – private equity deals worth between €25 million and €1 billion (£17.6 million and £703 million) – the authors noted a surge in the value of deals involving consumer-facing companies to 34.6 per cent of the industry’s total deal value at the end of the third quarter.

The data company said patchy consumer numbers from different regions could pose headwinds for the sector in 2016, with optimism in European powerhouse Germany falling. However, UK consumers are reporting record confidence, PitchBook says, meaning this sector could still be attractive in the coming months. In addition, the number of disruptive technology companies emerging in the lower end of the private equity market is likely to drive interest in the IT sector.

The rise of co-investment could also drive interest in long-term, stable consumer companies. Large pension funds in particular are putting pressure on private equity groups to invest alongside them directly in companies, rather than pay higher charges and performance fees for pooled vehicles.

Putting their capital to work

The giant Canada Public Pension Investment Board, a noted expert in private equity transactions, recently completed a $4.7-billion deal for an American pet supplies chain, co-investing with CVC Capital Partners.

As the biggest names in private equity seek to put their capital to work, they are venturing into the middle market, Duff & Phelps’ Mr Bartell points out, diversifying away from their traditional stomping grounds of the $1 billion-plus transactions.

“A lot of the firms wouldn’t normally be interested in [this area], but they are now,” he says, referring to sub-$200 million deals in particular. “They are willing to get their hands dirty. As long as the companies are growing, the bigger groups are buying in the middle market.”

Such companies are developing specialist teams for sector-specific funds, PitchBook says, and “can afford to pay heightened prices for up-and-coming brands, confident in their ability to tune up operations even if there is further accentuation of the economic downturn”.

There remains a tension in private equity, but as long as there are cash-rich buyers, they will find opportunities to make that money sweat.

Private equity exits