Grammy artist Jamiroquai’s Deeper Underground was apt as a soundtrack to the 90s movie Godzilla, in which a monster changes the face of many city buildings to then disappear underground. Roll forward 25 years and we too are going deeper underground.

Terms such as “iceberg homes” and “mega basements” are now commonplace as our interest in exploring and exploiting the realm below the topsoil continues while city designs keep changing.

Why go underground?

There are quite a few reasons for wanting to go underground. Space is a blunt answer. In crowded and established cities, such as London, New York or Tokyo, there is not much room left on the surface.

Also there is a practical limit to how high buildings can be built. Less favourable outdoor climates are another factor. In places such as Eastern Europe and Canada winters can become so bitingly cold that a stable and insulated underground environment offers an attractive reason to want to dig deep.

Equally, in places where there is intensive heat from the sun and high humidity, and in heavily industrialised cities with air-quality issues, burrowing below ground could be a solution. Furthermore, underground frees up the capacity to build laterally, rather than just vertically.

An advocate of the use and planning of underground space is Han Admiraal, chairman of the International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association’s Committee on Underground Space. He believes the next 20 years will require more work than the past 200 years to cope with the challenges humanity is facing on a global scale.

“Underground space has a unique role to play in meeting these challenges. The expansion and resilience of the world’s major cities will require planned and sophisticated use of all resources, including the valuable real estate of the underground,” says Mr Admiraal.

Prime examples

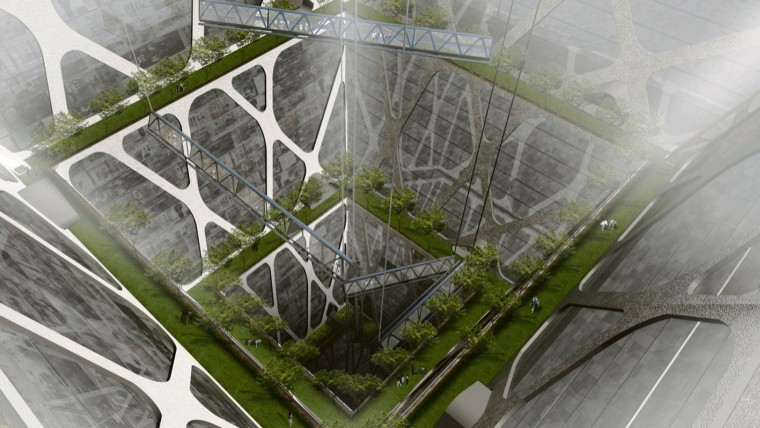

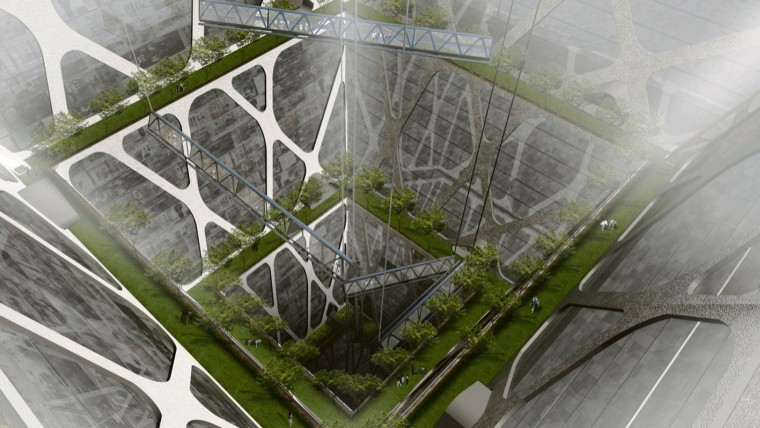

One such proposal is the Earthscaper in Mexico City – a 75-storey, 300m-deep steel and glass inverted pyramid. Capped by a glass roof, the designs include a museum, retail, offices and residential space for up to 100,000 people.

The Earthscraper concept is the brainchild of local architects BNKR Arquitectura, and was originally devised as an entry for an architecture competition in attempt to increase the space available for living and working in the city’s largest public square, which is bordered by the Metropolitan Cathedral, National Palace and Federal District Buildings.

Earthscraper, designed by BNKR Arquitectura, is a proposed 75-storey inverted pyramid underground project in Mexico City

“New infrastructure, office, retail and living space are required in the city, but there are no empty plots available. Federal and local laws prohibit demolishing historic buildings and height regulations limit new structures to eight storeys,” says BNKR Arquitectura chief executive Esteban Suarez. “The city’s historic centre is in desperate need of a makeover, but we have nowhere to put it – this means the only way to go is down.”

There is good reason for building below Singapore. According to Singapore’s Department of Statistics, a population of 5.53 million people share the island’s mere 719 square kilometres of land. This makes it the third most densely populated place on Earth.

The Jurong Rock Caverns beneath Singapore’s Jurong Island is South-East Asia’s first subterranean oil storage facility. Built by Hyundai Engineering and Construction for JTC for S$1.7 billion, the underground structure has five huge caverns 100 metres deep and 8 kilometres of tunnels, equivalent to nine storeys, to hoard hydrocarbons such as crude oil, condensate, naphtha and gas oil.

The nine storage galleries inside provide a volume of 1.47 million cubic metres, equivalent to the volume of 580 Olympic-sized swimming pools. This frees up to 60 hectares of usable land, or about 84 football fields, for industrial development above ground.

Drilling down into rock has also given rise to inventions. On the crowded Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York, the Lowline project uses innovative solar technology to illuminate an historic and disused underground trolley terminal. Natural sunlight is transmitted on to a combination of hexagonal and triangular anodised aluminium panels that form a moveable canopy of lenses and reflectors. Sunlight can be directed where it is needed at any one time to support photosynthesis, enabling plants and trees to grow.

The one-acre project, once complete in 2020, will be the world’s first underground park that attempts to add vibrant green space to the city’s dense concrete jungle. Its Lowline Lab already has more than 3,000 healthy plants and dozens of unique varieties, including pineapples and other exotic fruit, spread across 1,000 square feet. The lab acts as an interactive science experiment and community backyard to host public programmes, street fairs, art exhibits, school groups, lectures and open science education courses about the botanical research being conducted.

Pros vs. cons

Whether building underground is a one-stop solution to overcrowding remains unclear, however. The biggest barrier is cost, which involves the unknown, and this means increased risk. Even in Singapore, where land is at a premium, state developer JTC says the cost of building an underground science park for 4,200 workers would be 50 per cent more than an above-ground facility.

Building underground has also brought a fair share of critique. “When the Pollution Prevention Guidelines 3 were introduced, they effectively imposed a requirement for house builders to increase development densities in order to conserve the most finite of resources – development land,” says Stephen Wielebski, senior technical consultant at the Home Builders Federation.

A simple aim of relieving congestion and opening up surface space for alternative uses comes with a hefty price tag

“The resultant increase in high-rise development was not the success many had perceived. Basement construction would fall into this same category given the number of technical issues that have to be overcome.”

This means a simple aim of relieving congestion and opening up surface space for alternative uses comes with a hefty price tag. There is also the constant challenge of water ingress and the need to compete for space with other existing necessities, such as sewerage systems, electrical infrastructure, underground railways, subways and tunnels for roads.

“In the UK, the fiscal dynamics may make it an attractive proposition for ‘iceberg homes’ in London, but elsewhere the cost of construction and market responsiveness could easily see project viability compromised,” says Mr Wielebski.

It would be wise to weigh up the cost of any underground venture in respect of social housing and ways of living, but we should not condemn going underground to a world of fantasy just yet. Godzilla is safe, for now.

JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT

Hailed as the “terminal of the future”, Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport development at the heart of Changi International Airport’s Terminal One, was “borne out of a desire to increase the terminal’s capacity”, says spokeswoman Samantha Lee.

Hailed as the “terminal of the future”, Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport development at the heart of Changi International Airport’s Terminal One, was “borne out of a desire to increase the terminal’s capacity”, says spokeswoman Samantha Lee.

Given the practical and safety regulations associated with construction in and around airports, Jewel Changi Airport will feature a ten-storey multicomplex, offering retail, a 130-room hotel, attractions and facilities for airport operations underground. The S$1.7-billion (£880-million) joint venture by Woh Hup and Obayashi Singapore is expected to open in early-2019.

In the middle of the project’s steel and glass donut-shaped structure, the Rain Vortex, a 40-metre water feature, will be logged as the world’s tallest indoor waterfall with 500,000 litres of water circulated via a storage tank and pump.

As part of its sustainable design, rainwater will also be allowed to flow through naturally. The downward air currents created by the waterfall will cool the internal environment. Photovoltaic panels will harness natural light into renewable energy, and at night the Rain Vortex will transform into a light and sound show.

Native trees, ferns and shrubs will feature in four different gateway gardens. These will have playgrounds and walking trials. Subway links will connect all the airport terminals and the Mass Rapid Transit train network.

The opening of Jewel Changi Airport in 2019 is expected to increase passenger handling capacity by 35 per cent from 17.7 million in 2013 to 24 million passengers a year. Designed by world-renowned architect Moshe Safdie, it is likely to further cement Changi Airport’s status as Skytrax World’s Best Airport.

Why go underground?

Prime examples