Adidas’s newly opened, highly automated “speedfactory” at Atlanta in the United States provides a vivid illustration of the possibilities and limitations of reshoring.

Reshoring has happened to some degree over the past ten years as rising wage costs in China and elsewhere in Asia eroded the previous benefits of offshoring. Some companies also had problems with quality, intellectual property theft and long, vulnerable supply chains. Now reshoring has become a hot political issue, particularly since Donald Trump’s election as US president.

President Trump pledged to bring manufacturing jobs back to the US; his tariffs on imports from China, Canada and Europe aim in part to achieve that. In the UK, there is debate about whether Brexit could accelerate reshoring or further weaken manufacturing.

Globally, the question is whether reshoring amounts to a trickle or something more substantial

Atlanta’s production, like that of its sister plant in Germany, is three times faster and also more flexible than at Adidas’s Asian plants. It can make short-run products designed for local markets, such as AM4NYC (Adidas made for New York City) trainers, created for New York’s urban streets.

These “speedfactories”, however, each employ only 160 workers, compared with 1,000 or more in a typical factory in Asia. Adidas plans eventually to take these technologies into factories in China, its fastest-growing market.

“Our production landscape is 90 per cent Asia-based. I do not believe, and it’s a complete illusion to believe, that manufacturing can go back to Europe in terms of volume,” according to Kasper Rorsted, Adidas’s chief executive. “And that goes for the entire industry.”

Can reshoring restore manufacturing to its former glory?

Globally, the question is whether reshoring amounts to a trickle or something more substantial and whether it can restore significant employment, given today’s levels of automation.

Reshoring appears so far to have been greater in the US, encouraged by low energy costs as a result of the shale gas boom, than in Europe. Companies such as General Motors, Boeing, Ford and Intel have reshored thousands of jobs over the past decade.

There is conflicting evidence about how strong the trend is. The Reshoring Initiative, a lobby group, reckons 576,000 US factory jobs have been created through foreign investment or reshoring since manufacturing employment’s low point in 2010, while three to four million remain offshore. It believes President Trump’s corporate tax cuts, reduced regulatory costs and a lower dollar make this a good time to reshore.

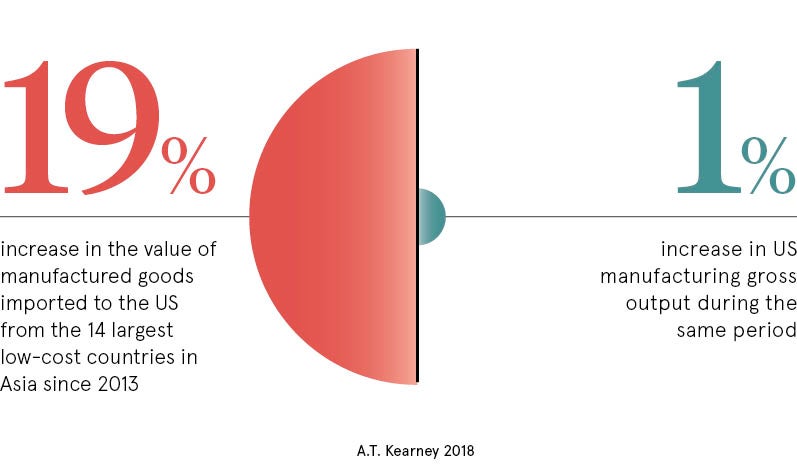

However, consultants A.T. Kearney argue that reshoring is “in reverse”. They calculate that since 2013 imports of manufactured goods from the 14 largest low-cost countries in Asia have increased in value by 19 per cent, while US manufacturing gross output has grown by only 1 per cent.

Examples of reshoring in the UK include vacuum cleaner maker Gtech, which plans to shift some production from China to Worcestershire, and shoemaker Clarks, which is bringing manufacturing of desert boots home to Somerset from Asia. Elsewhere in Europe, Le Coq Sportif, the sportswear maker, is bringing production back to France from Vietnam.

A survey in 2014 by EEF, the manufacturers’ federation, found that one in six UK companies had reshored production in the previous three years. The main reason was quality, followed by certainty and speed of delivery, transport costs and risk of supply chain disruption.

“Rightshoring” is more important than comprehensive reshoring

The numbers depend partly on definition. A survey by the University of Warwick’s Manufacturing Group, conducted for Reshoring UK, an industry body, found only 13 per cent of companies had directly reshored. But 52 per cent had indirectly reshored, meaning they had decided to increase capacity at home instead of abroad.

Janet Godsell, professor of operations and supply chain strategy at Warwick, says for multinational companies the question is what makes sense in terms of supply chain design. Some have a system that is global for raw materials, regional for manufacturing and local for distribution.

What we should be focusing on is not reshoring but ‘rightshoring’, making sure we put things in the right place

Companies look at total cost, including transport and inventory, rather than simply labour costs, as tended to happen in the 1990s’ offshoring wave. The need to reduce lead times and customise products for local consumers are further factors.

“What we should be focusing on is not reshoring but ‘rightshoring’, making sure we put things in the right place,” says Professor Godsell, who adds that the emerging trend is “distributed manufacturing” or having a number of plants around the world, which reduces disruption risk.

The road to reshoring is not a clear path

Reshoring is not easy or cheap, notably because many countries have lost manufacturing skills as a result of previous offshoring. Mobile phone handset maker Motorola, then owned by Google, closed its Moto X factory in Texas in 2014 after less than two years because costs were high and it could not sell enough in the US market.

Companies find it hard to recruit skilled workers and sometimes have to bring in managers from overseas to design production processes.

Further barriers in the UK include high energy costs and the question of whether banks will lend to small suppliers to invest in equipment, says John Glen, economist at the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply. He adds: “We have reached an equilibrium where, in areas in which the benefits are relatively clear, you will still get offshoring. Where they are not, reshoring will occur.”

Will political pressures lead to more reshoring? Brexit could be double-edged. UK manufacturers will try to build up supply chains at home to avoid tariffs and other barriers, but European Union-based companies may use fewer UK suppliers.

President Trump’s tariffs might encourage some US companies to reshore from China, but others could move instead to countries such as Mexico or Thailand.

Dr Glen concludes: “If you have significant protectionism, you will have significant reduction in global economic activity. So while there may be benefits from reshoring, total global activity could decrease significantly.”

Can reshoring restore manufacturing to its former glory?