The National Health Service is going through a period of unprecedented change. The NHS Five-Year Forward View, published at the end of 2015, is a blueprint for a sustainable health service that delivers high-quality care to patients, still free at the point of delivery.

At the heart of the transformation proposed by Simon Stevens, NHS England chief executive, is a profound re-engineering of the health service through technological innovation. It will require greater integration between the multiplicity of providers of health and social care, and a sharing of data on an unprecedented scale, while protecting the integrity of a system holding the most sensitive information.

It is a mighty challenge for an organisation with a poor track record in information technology, where referral letters, trolleys groaning under patient notes and fax machines are still part of its fabric. While the NHS remains a source of national pride for the care it provides, it is increasingly difficult to defend the health service’s slow progress in embracing the latest technology for the benefit of patients.

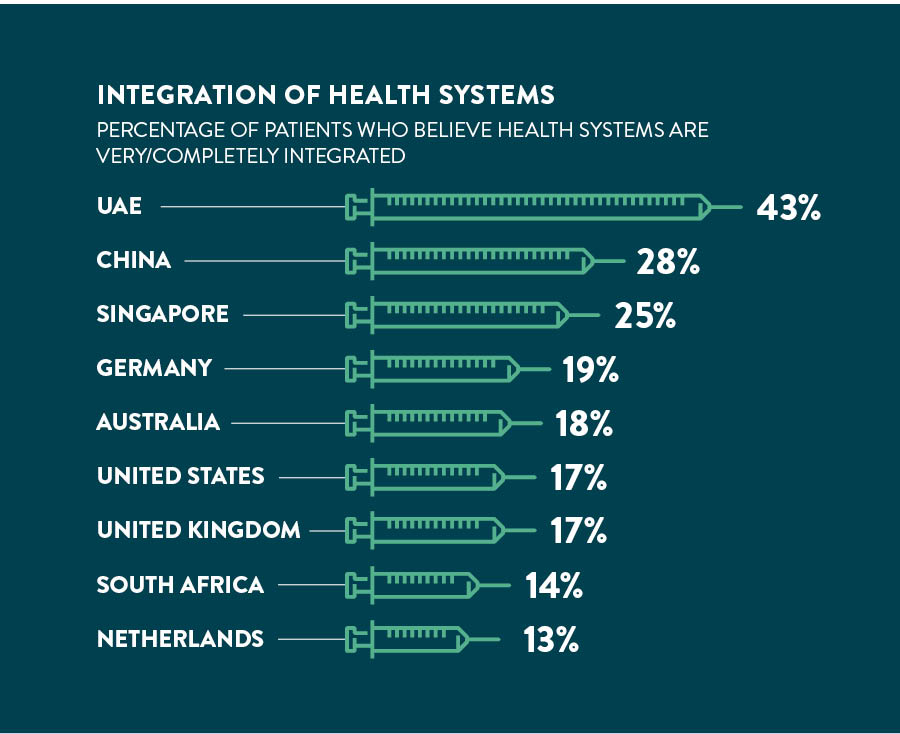

The UK performs well below the 13-country average when it comes to integration of healthcare systems and the adoption of connected healthcare

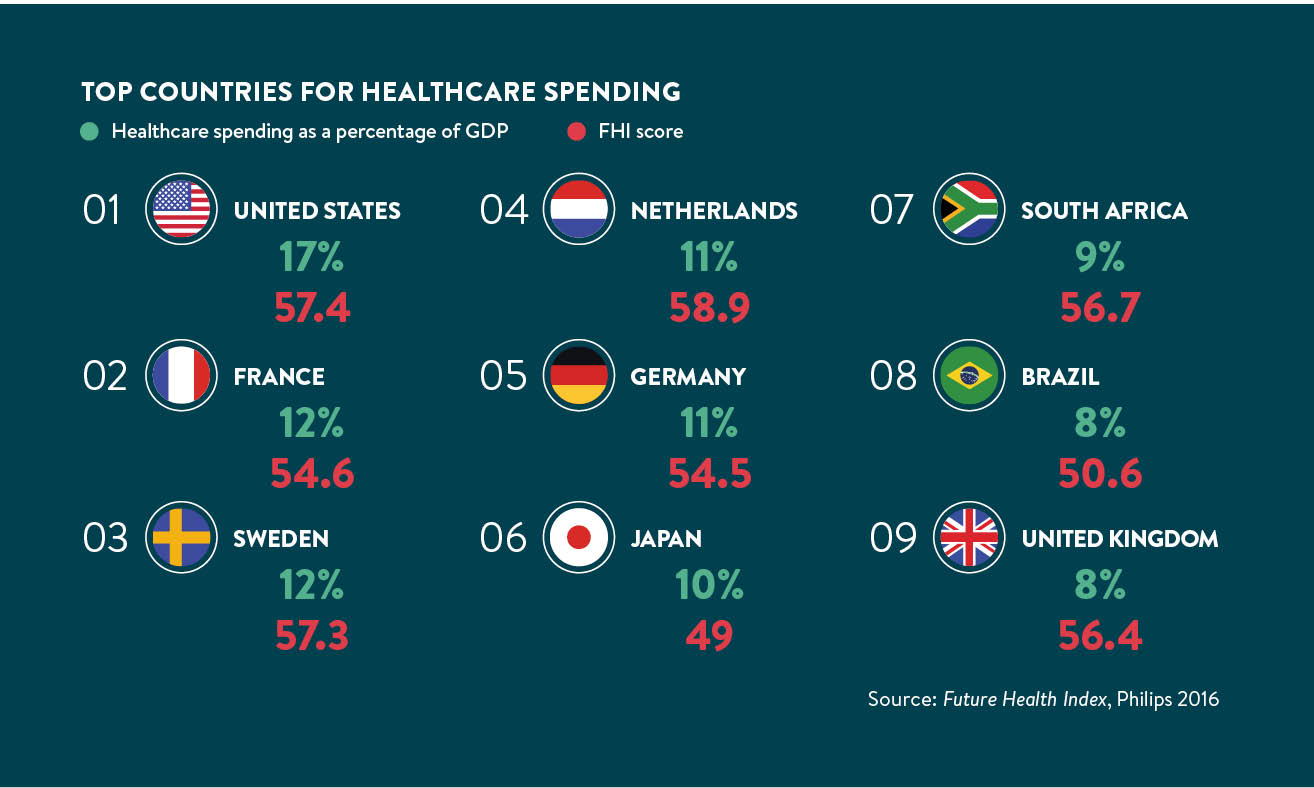

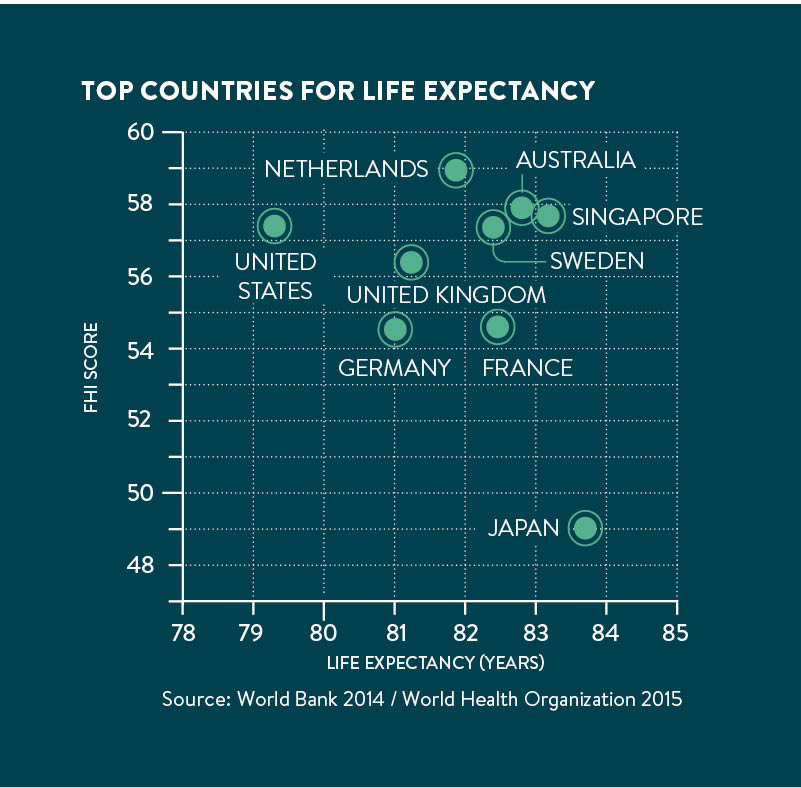

This is certainly true when the performance of the NHS is measured against that of health systems in other countries confronted by similar challenges, including an ageing population and prevalence of long-term conditions at a time of economic austerity. The 2016 Future Health Index, which measures a country’s readiness to meet some of these key healthcare challenges, places the UK ninth out of thirteen countries, based on a range of measures.

UK slow to adopt

The UK scores highly on access, due to its universal healthcare coverage. But the country performs well below the 13-country average when it comes to integration of healthcare systems and the adoption of connected healthcare. And that will be a major concern for Mr Stevens as he embarks on his NHS revolution.

The index was commissioned by Philips, the technology company, and produced by the Institute for the Future, an independent non-profit research group dedicated to identifying emerging trends that will transform global society. The index is based on the input and self-reported behaviours of patients and healthcare professionals throughout 13 geographically and developmentally diverse countries to produce a snapshot of how healthcare is experienced on both sides of the patient-professional divide.

Some of the countries that lead the index, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the Netherlands, are prosperous; China comes in third place, well ahead of the United States and the UK. Japan, the world’s third largest economy, comes in last, trailing less-developed countries including South Africa and Brazil.

Optimism from emerging countries

Emerging countries tend to lag their developed counterparts when it comes to access to healthcare, from prevention to diagnosis and treatment. For example, just 40 per cent of Brazilian patients agree they have access to the information and resources they need to live healthily, compared with 68 per cent in Australia and 70 per cent in Singapore.

Yet optimism around connected care is strikingly more pronounced in emerging countries, perhaps because they are not burdened by ageing legacy systems. Almost three-quarters of healthcare professionals in emerging economies see a future where everyone owns devices, software and mobile applications to help manage health. In developed countries, 44 per cent think the same. Emerging countries also appear to be earlier adopters of technology.

Bringing together the disparate segments of healthcare systems has proven elusive everywhere. But there are often more positive assessments of the state of integration in emerging countries. In the UAE, 43 per cent of patients feel the health system is very or completely integrated, the highest rate among countries polled, followed by China (28 per cent) and Singapore (25 per cent). This compares to 11 per cent in the US and 6 per cent in France.

The UK’s poor overall ranking reflects low perceived levels of integration and adoption of connected-care technology. On integration the UK scores 53.7 against the index average of 55.8 and on technology adoption it scores 45.3 against 47.8.

Concern over cost and bureaucracy

The index provides a number of key findings for the UK. Healthcare professionals and patients are acutely aware of the lack of integration in the health system, as well as the importance and potential benefits of integration. Patients are more likely than healthcare professionals to believe technology can play an important role across the health continuum. Healthcare professionals have reservations about connected-care technologies in general, which may limit their willingness to embrace these technologies fully.

Finally, concerns over cost and bureaucracy are significant, and must be addressed in the implementation of healthcare integration and connected-care technologies.

What does market leadership look like? The UAE is first among the 13 countries surveyed for the index, ranking above average on all measures. Satisfaction with the healthcare system, particularly with regard to access, is high. The gap between the UAE and 13-country total is greatest in perceived access to homecare. Connected-care technology is viewed positively by healthcare professionals and patients, and there is a high level of knowledge and usage. Interest in online interactions and digital information-sharing is high, especially among healthcare professionals.

The Netherlands, whose healthcare system is more directly comparable to the UK, comes second in the index, outscoring the UK on all principal measures. A blend of private insurance and state funding gives the edge in terms of access.

The UK would do well to acknowledge the principal learnings from the index, shared by this unique survey of healthcare professionals and patients around the world. It is clear that in developed countries rigorous data and privacy regulations present challenges to the free flow of information needed in more technology-driven healthcare systems.

Technology is a generational issue, both for healthcare professionals and for patients, suggesting that adoption will rise in the years ahead as a digitally native generation comes of age. Data is proliferating, but doesn’t travel as more data than ever is being gathered although it is not yet being shared between institutions or agencies.

Bureaucracy is a major stumbling block to the further co-ordination of healthcare, particularly in countries with large publicly funded systems such as the UK, the Netherlands and Sweden. Trust is key and in many cases is lacking, which creates mistrust around the sharing of sensitive data.

Sizeable majorities of healthcare professionals and patients view integration as an important goal with a positive impact on the health of a population. But perceptions of high cost are a significant concern across developed and emerging economies.

Most of these concerns have come to the fore in the UK, as the NHS grapples with the complexities of implementing a genuinely connected healthcare system for all. They are certainly high on the agenda for Professor Bob Wachter, who has been asked by the Department of Health to review computer systems across the NHS. His review is seen as a crucial step to support the NHS in its ambition to be a paperless organisation by 2020, with all patient records held digitally.

The Wachter review will be delivered later this year to the National Information Board (NIB), which was established by the Department of Health to put data and technology safely to work for patients and healthcare professionals. An example of NIB’s work is the My NHS website, which brings together information from a range of data sources to make it possible to compare services and organisations. The ambition is that intelligent transparency will drive a cultural shift that will permeate the entire health and social care system, and be embraced by the public and patients.

If this can be achieved it will represent a major step towards lifting the UK towards the top of the next Future Health Index, to the benefit of patients and healthcare professionals.

UK slow to adopt

Optimism from emerging countries