In countries across the world, the rule of law is under threat. In Hong Kong, Turkey, Hungary and Poland, autocrats and extreme right-wing parties muzzle courts, restrict the judiciary and ignore human rights.

The latest World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index shows that a majority of countries worldwide saw their scores decline in the areas of human rights, checks on government powers, and civil and criminal justice. Overall, more countries’ rule of law score declined (34 per cent) than improved (29 per cent), compared with 2016 ratings.

Reduced adherence to the rule of law anywhere threatens development everywhere

The trend is deeply troubling. “We are witnessing a global deterioration in fundamental aspects of the rule of law,” says William H. Neukom, WJP founder and chief executive. “Reduced adherence to the rule of law anywhere threatens development everywhere.”

Even mature democracies, such as the UK and United States, that were architects of the international rules-based order, have seen their rating drop one point, their politics fallen victim to populism, occasioning attacks on judges that would have been unthinkable ten years ago.

R. Daniel Kelemen, professor of political science at Rutgers University, points to the worldwide rise of populism as a significant cause. Populist narratives, which bluntly draw a line between “the people” and “the elites”, almost always condemn judges to the latter category. When populist leaders attain power and judges enforce constitutional limits, as they ought, they are caricatured as “thwarting the will of the people”.

“It’s right out of the autocratic playbook,” says Professor Kelemen. “Orbán did it in Hungary, it is being replicated in Poland and Trump would likely do the same in the United States, but for the strength of the US judiciary and its decentralisation.”

Professor Murray Hunt, director of the Bingham Centre for Rule of Law and former legal adviser to Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights, identifies a worldwide retreat from international legal obligations and a growing hostility towards international courts, including the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

“The reassertion of national sovereignty over the claims of international courts is a worldwide phenomenon that goes hand in hand with populism and the return of authoritarian nationalism,” warns Professor Hunt. “This resurgence of inward-looking, nation state-first outlooks poses a very large challenge to the rule of law, because so much of the rule of law architecture has depended since the Second World War on these institutions that were set up thereafter.”

Through the Bingham Centre, he believes that innovative approaches to countering attacks on the rule of the law are “absolutely crucial”. “We have to think in a far more imaginative way than we have in the past about how we defend the rule of law and advance it,” says Professor Hunt. “We need to get out there and explain what the rule of law means in an accessible way and in practical terms.”

Meaningful clarity and consensus over definition of the rule of law, which is so often impeded by its abstraction, is a crucial first step.

Lord Bingham, the senior law lord after whom the centre is named, gave a definitive account in his accessible 2010 book The Rule of Law. In it, the rule of law is outlined through a cluster of core concepts, including legal certainty, equal treatment and non-discrimination, non-arbitrariness, permission for democratic parts of the constitution to scrutinise the executive, democratic scrutiny of widely delegated powers, access to courts, access to legal remedies, protection of human rights, and international legal obligations.

How best to legislate for human rights, however, is contested by some. While in favour of human rights in general, Richard Ekins, professor of law at Oxford and director of the Judicial Power Project at the Policy Exchange think-tank, argues that the Human Rights Act and ECHR undermine UK rule of law. For him, the “judicialisation” of politics is itself a threat.

For Professor Hunt, the most urgent objective of the centre is to “democratise the rule of law”. It is crucial, he believes, that all aspects of society have a shared stake in and responsibility to defend and promote the rule of law. “It should include all actors,” he says, “Government, Parliament, the judiciary, business, media and individuals.”

Business is only latterly emerging as important agents in the defence of the rule of law. Through its business network, the Bingham Centre builds capacity among in-house counsel, shifting thinking from compliance issues to identifying and mitigating rule of law risks in the countries where they operate. Eventually, the programme hopes to extend to board-level members, with the goal of positioning rule of law as a strategic business imperative.

In the UK, the centre aims to make discussions of the rule of law extend from school classrooms to the heart of Parliament. Legal literacy classes, to be included in the citizenship curriculum, would teach school children, from primary school upwards, to think critically about real-life applications and conflicts around the rule of law.

The All-Party Parliamentary Group on the Rule of Law, founded three years ago on the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carter, and for which the Bingham Centre is secretariat, encourages MPs to discuss matters of business through a rule of law lens.

The digital age has brought with it challenges to the rule of law that society has struggled to make sense of at every level. Questions around the responsibility of big tech to police extremists, effects of social media on children, implications of artificial intelligence and who owns big data present regulatory challenges that “far outstrip our institutions’ ability to keep up with them, let alone be ahead of the game”, says Professor Hunt.

The UK’s withdrawal from the European Union presents its own rule of law concerns. “Whatever your view of Brexit – whether it is a good thing or a bad thing – it poses enormous rule of law challenges,” Professor Hunt adds. “Leaving the EU, given how long we’ve been a member of it and the degree of regulatory immersion, is really tantamount to ripping up your constitution in one go without having first decided what you’re going to replace it with. There could be an enormous problem in terms of legal discontinuity and legal uncertainty.”

The EU, meanwhile, faces rule of law challenges that undermine the very principles upon which it was founded. Worse than the euro crisis, Brexit and the migration issue, Professor Kelemen argues the flagrant disregard for the rule of law displayed by Poland and Hungary presents “the greatest existential crisis in the EU’s history”.

Perhaps more than ever, the defence of the rule of law will require constant vigilance, ingenuity and effort. In Lord Bingham’s words: “It remains an ideal, but an ideal worth striving for, in the interests of good government and peace, at home and in the world at large.”

Case Studies

UK

In January 2017, in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote, the UK Supreme Court found in favour of Gina Miller, who brought a case arguing that Parliament must have a vote to trigger Article 50 and formally initiate Britain leaving the European Union. The judgment, which sets a far-reaching constitutional precedent and upholds parliamentary sovereignty, was hailed by supporters as setting clear limits on the extent of the government’s executive powers.

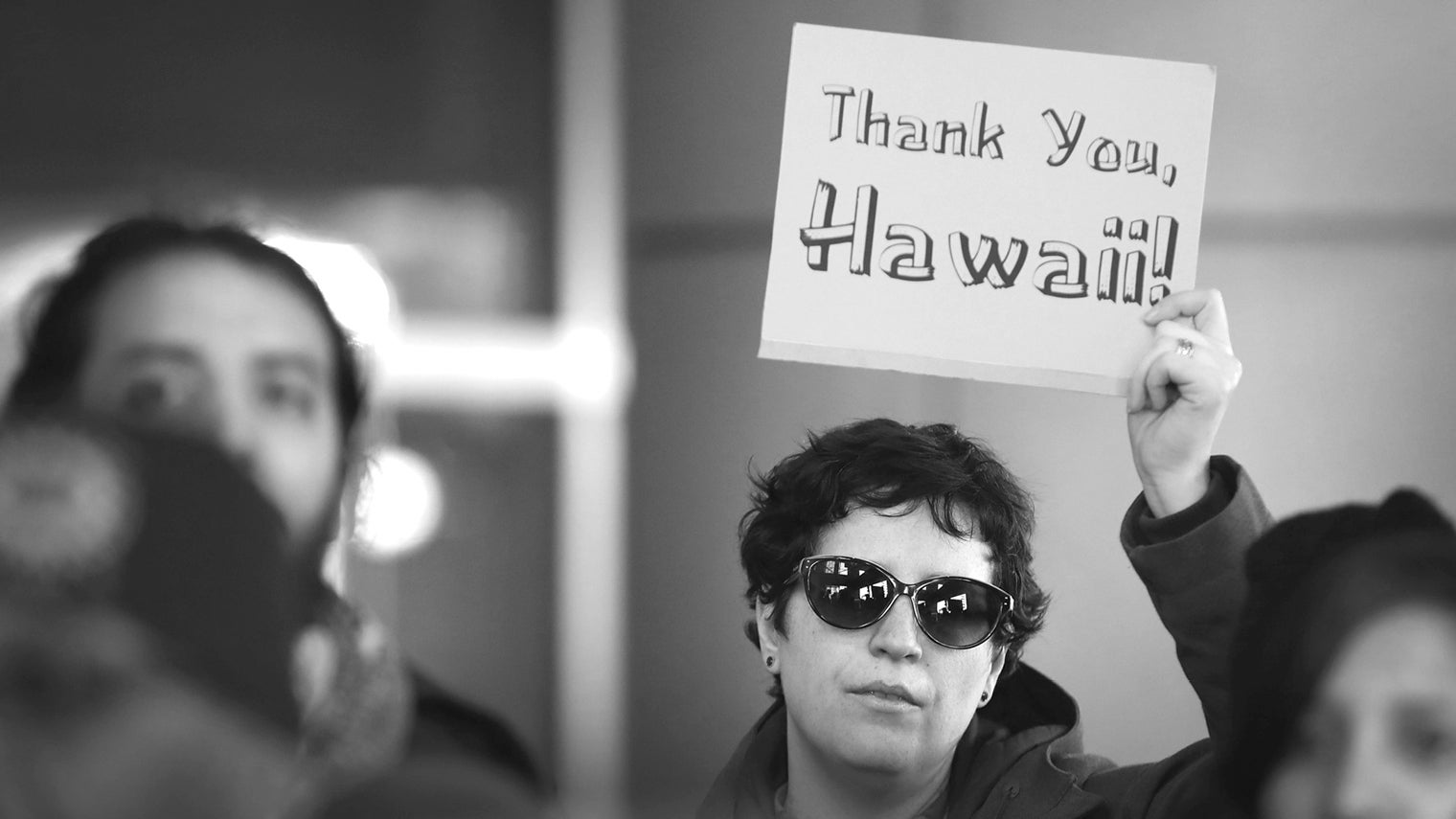

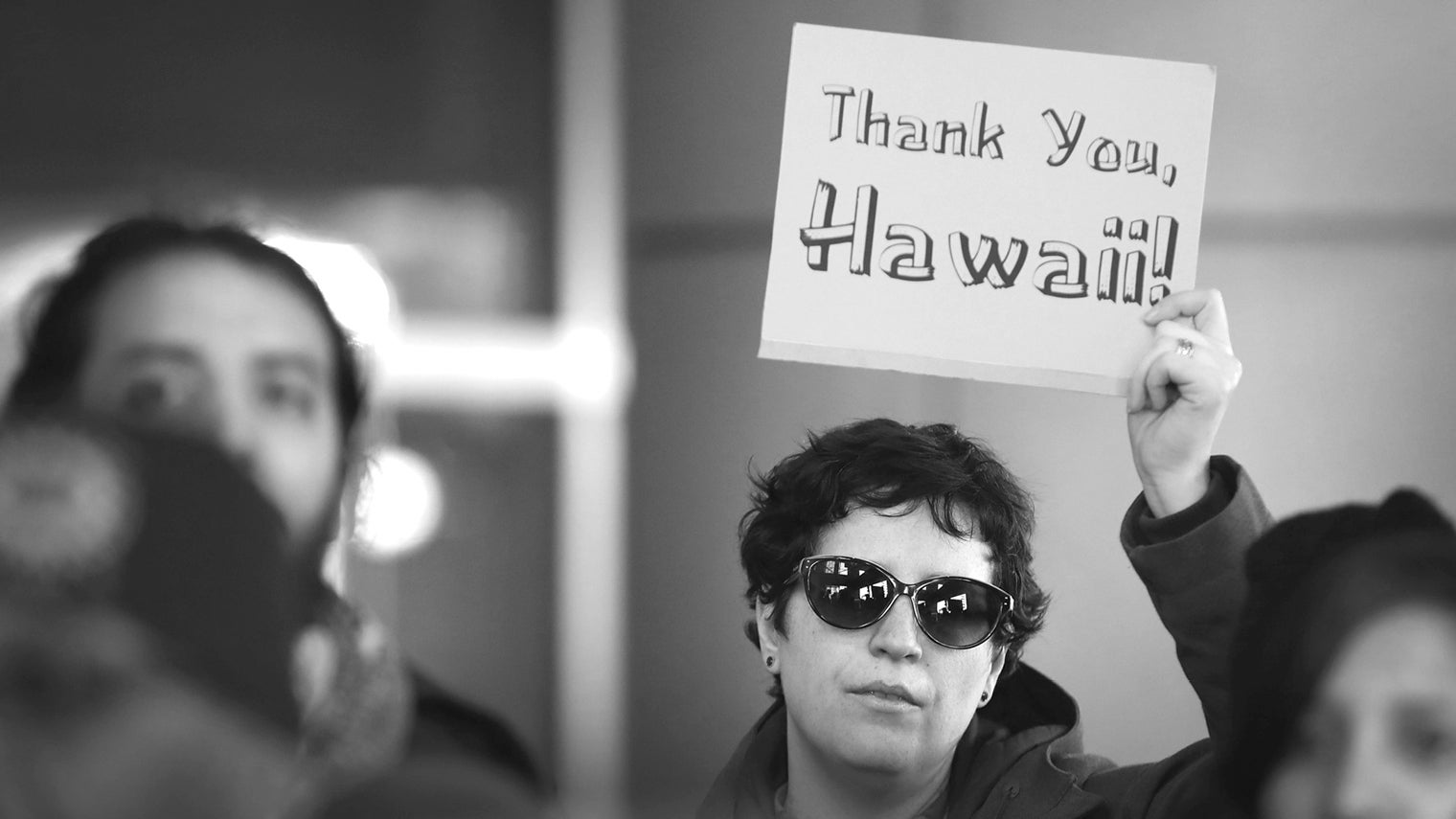

United States

In May 2017, Hawaii became the first US state to file a lawsuit against President Donald Trump’s revised travel ban, arguing the order would harm the state’s economy and educational institutions, and would prevent Hawaiians with family members in the six targeted countries from reuniting. Separately, in an amended complaint, a Hawaii district judge blocked the executive order, arguing that it remained incompatible with freedom of religion protections in both the state and federal constitutions.

Hungary

In December 2017, the European Union took Hungary to the European Court of Justice over Hungarian President Viktor Orbán’s crackdown on political freedoms and persecution of a leading university. The European Commission said the legislation ran counter to academic freedom and the right to run a business under the EU’s charter of fundamental rights. Hungary is also being referred over a law that requires non-governmental organisations receiving foreign donations to label themselves as “supported from abroad”.

Case Studies