Lloyd Blankfein, chief executive of Goldman Sachs, warns that the City of London “will stall” and see its position as a global financial centre eroded as a result of UK’s decision to leave the European Union.

His bank, which has had a London presence since 1970 and currently employs 6,000 in the capital, has already started to shift hundreds of workers out of London to Frankfurt, Paris and Warsaw as Brexit looms. There have been rumblings that Goldman’s London-based staff will eventually dwindle to 3,000 as a result of last June’s referendum result.

Brexit was always going to be tough for the UK’s highly internationalised financial services sector, whose total annual revenues are £200 billion, according to consultants Oliver Wyman.

Hard Brexit realities

Given the Theresa May government’s recent policy pronouncements on Brexit, which have been largely underpinned by her focus on limiting immigration, there’s a widespread acceptance that Brexit will be much “harder” than some had envisaged, and will include full departures from the single market and customs union.

UK financial services, a sector which is also clustered around regional centres including Edinburgh and Leeds, derives 25 per cent of its annual revenues – around £45 billion to £50 billion according to Oliver Wyman – from sales to other EU states.

So some or all of these businesses are vulnerable to drifting away to places such as Frankfurt, Paris, Dublin and Luxembourg, and each of these centres has since last June been seeking to woo decision-makers in the sector.

In prime minister May’s Lancaster House speech on January 19, she made clear she favoured a hard Brexit, effectively killing off any residual hope among City firms they would be able to retain the “passporting” rights, which enable them to sell products and services freely across the EU.

The tone from Downing Street in recent months, including Mrs May’s triggering of Article 50 on March 29 and manifesto launch on May 18, cemented doubts the industry would be able to wring any special favours from the UK government once Brexit talks commence.

The mood music in the City of London has swung from panic, amid rumours of absolute carnage in the Square Mile, to confident assertions that the effects are going to be marginal and London will retain its financial crown.

Moving jobs

In recent months, in response to entreaties from regulators on both side of the English Channel, the top management of financial firms, especially in the most affected sectors of investment banking, asset management and insurance, have been working on contingency plans.

In some cases these include physically relocating everyone who deals with EU-based clients, plus all the associated risk and trading functions, as well as the capital that supports them, to other European counties. The Bank of England has given banks and other financial firms until July 14 to present their plans.

EU regulators have made clear that financial firms will not be able to circumvent Brexit by establishing empty-shell companies in EU member states. “To be clear, we will only grant licences to well-capitalised and well-managed [firms],” according to European Central Bank (ECB) executive director Sabine Lautenschläger. “Any new entity must have adequate local risk management, sufficient local staff and operational independence.”

The ECB, in particular, is concerned that the stability of the EU’s financial system could be at risk in the event of a “cliff-edge” Brexit, a chaotic scenario in which firms are under-prepared and the terms of trade for cross-border finance have not been nailed down.

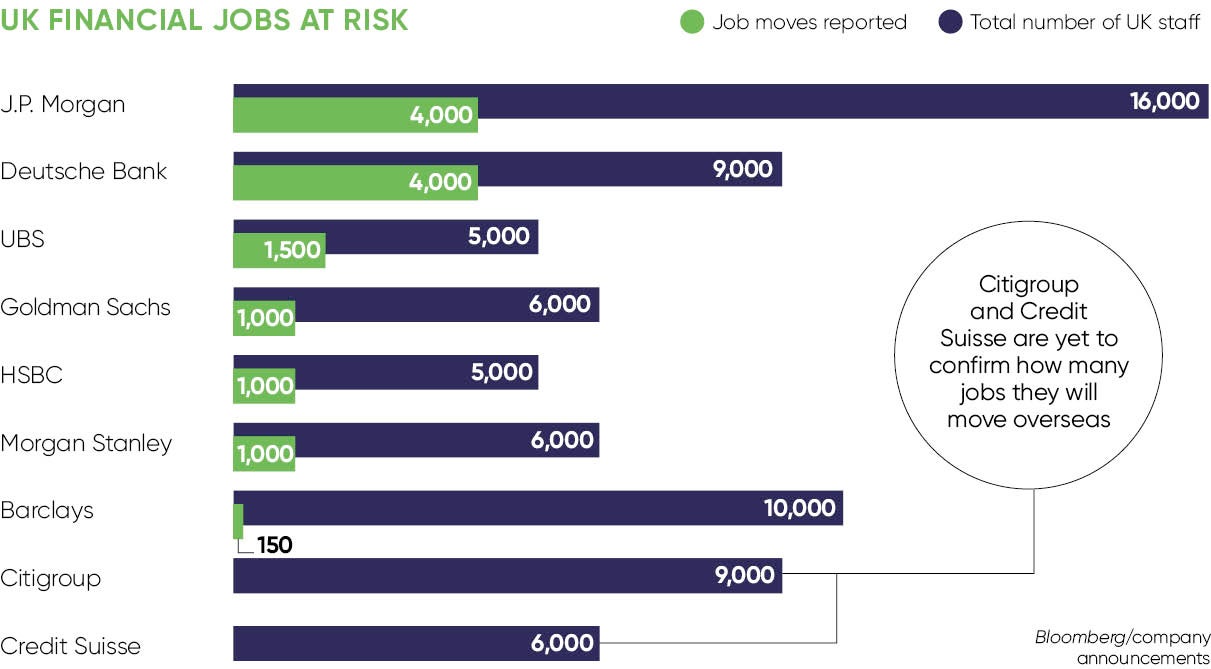

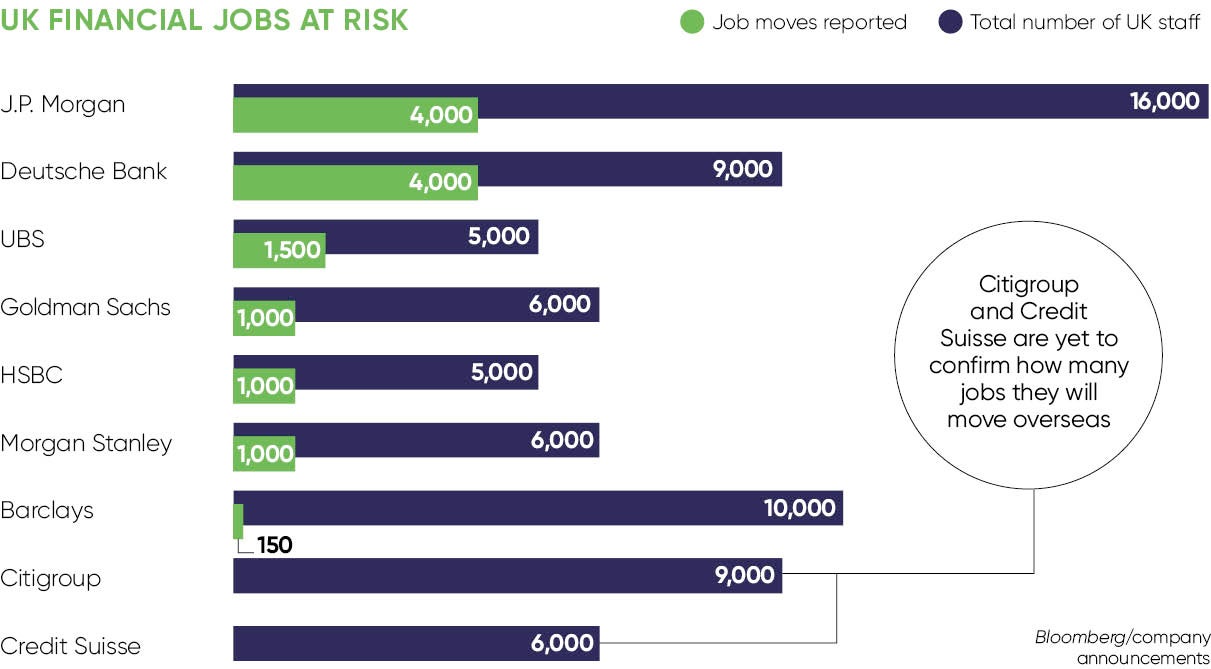

Estimates of how many jobs could ultimately be lost in the UK financial and professional services sector range wildly from 9,000 to more than 230,000

To date, some 30 to 40 per cent of UK-based financial firms have already started to relocate, or to make plans to relocate, thousands of staff to financial centres elsewhere in the EU. The banks currently intending to move the most posts to EU financial centres are J.P. Morgan and Deutsche Bank, each of which intends to transfer up to 4,000 jobs.

J.P. Morgan is likely to be moving them to its existing bases in Frankfurt, Dublin and Luxembourg, while Deutsche Bank, which has had a London presence since buying Morgan Grenfell in 1989, has indicated it will shift 4,000 jobs from London to Frankfurt. In January, HSBC said it expects about 1,000 or 20 per cent of the investment banking jobs it has in London to move to Paris

Insurers including AIG and Hiscox are favouring Luxembourg as an EU trading hub, as does the Prudential’s asset management arm M&G Investments. Paris is also gaining ground as a potential base for asset management firms, especially since the election victory of centrist president Emmanuel Macron. Insurer Standard Life, which is in the throes of merging with rival Aberdeen Asset Management, is plumping for Dublin.

Estimates of how many jobs could ultimately be lost in the UK financial and professional services sector range wildly from 9,000 to 10,000 estimated by Bruegel to more than 230,000 forecast by EY.

The future

There is currently a fierce debate over whether the clearing of euro-denominated derivatives – a major business for London where it supports 83,000 jobs – is going to be forced away by Brexit. The early signs are that the European Commission will enact new legislation which will require UK-based clearing houses of euro-denominated transactions either to relocate to the EU or be directly regulated by the European authorities.

But Catherine McGuinness, head of policy for the City of London, has warned this could cause chaos. “Uprooting and offshoring [euro clearing] would not only be vastly complicated, but also vastly damaging and potentially destabilising,” she says.

Some banks may choose to shrink their European operations or retreat back to Wall Street as a result of Brexit rather than go through with the hassle of preparing for the unwanted divorce, which will reduce competition and diminish access to capital in Europe.

Jonathan Wills, a partner in Oliver Wyman, warns that the cost of financial services will rise as a result of Brexit. He predicts that the return on equity of European investment banks will fall by about five percentage points or by around $1.5 billion across the industry, as a result of Brexit induced costs, uncertainties and inefficiencies. And bankers, including Goldman Sachs’s Europe head Richard Gnodde, have made no secret of the fact they will pass the extra costs on to their clients.

Hard Brexit realities

Moving jobs