1. Lack of meaningful data

Businesses must make a proactive effort to conduct anonymous surveys and other research to quantify the scale of the problem, and report the results at board level. Companies that wait for employees to come forward with complaints may be holding their breath if employees aren’t comfortable with voluntarily reporting harassment.

“There needs to be accurate information for boards,” says Kristy Grant-Hart of Spark Compliance Consulting. “If I was a chief compliance officer, I would make sure my compliance and engagement survey includes questions on sexual harassment. Have employees experienced any or seen any? Break

the numbers down by country or business line, so problems can be identified strategically.”

Useful metrics include the number of harassment complaints received via a whistleblowing hotline, number of staff given training, number of times anti-harassment policies were accessed and data from anonymous surveys asking staff if they have been a victim but did not report the incident.

2. Shortage of guidance

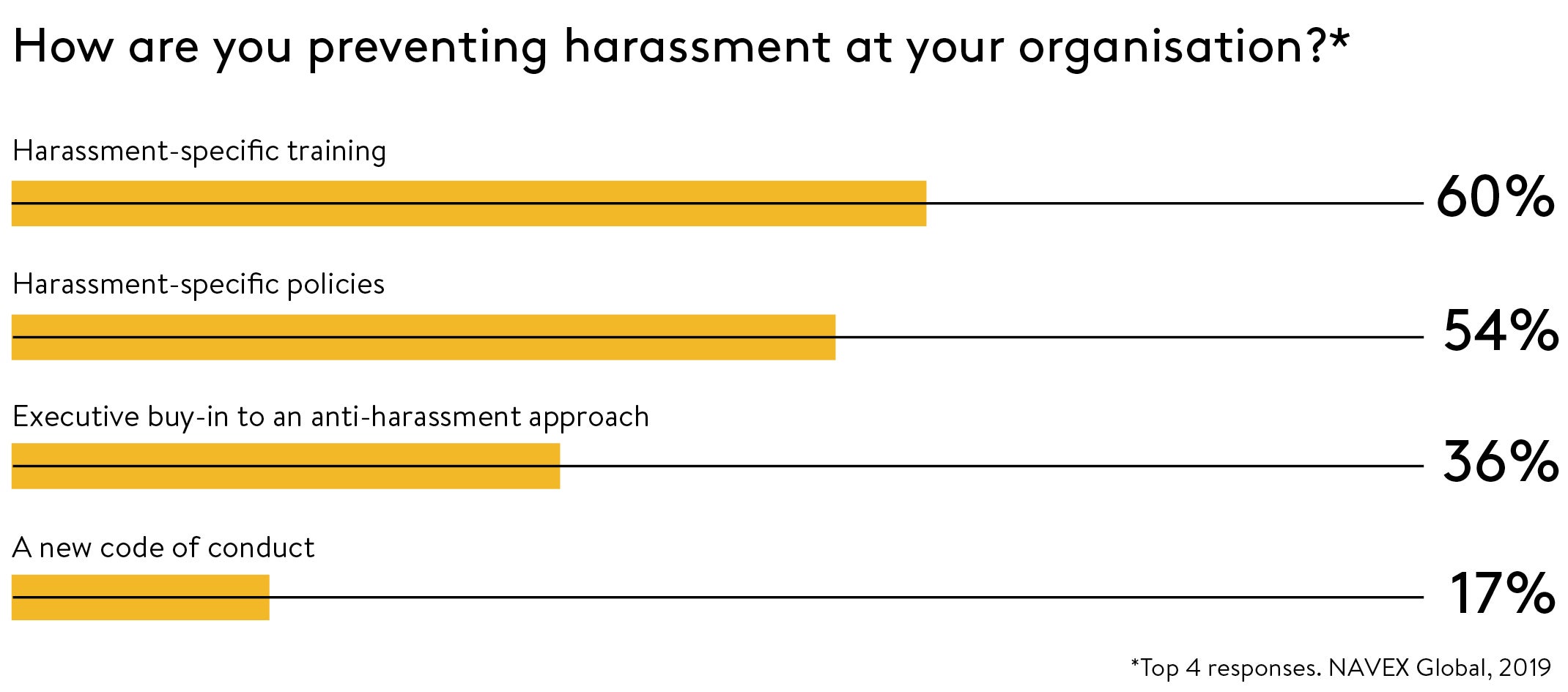

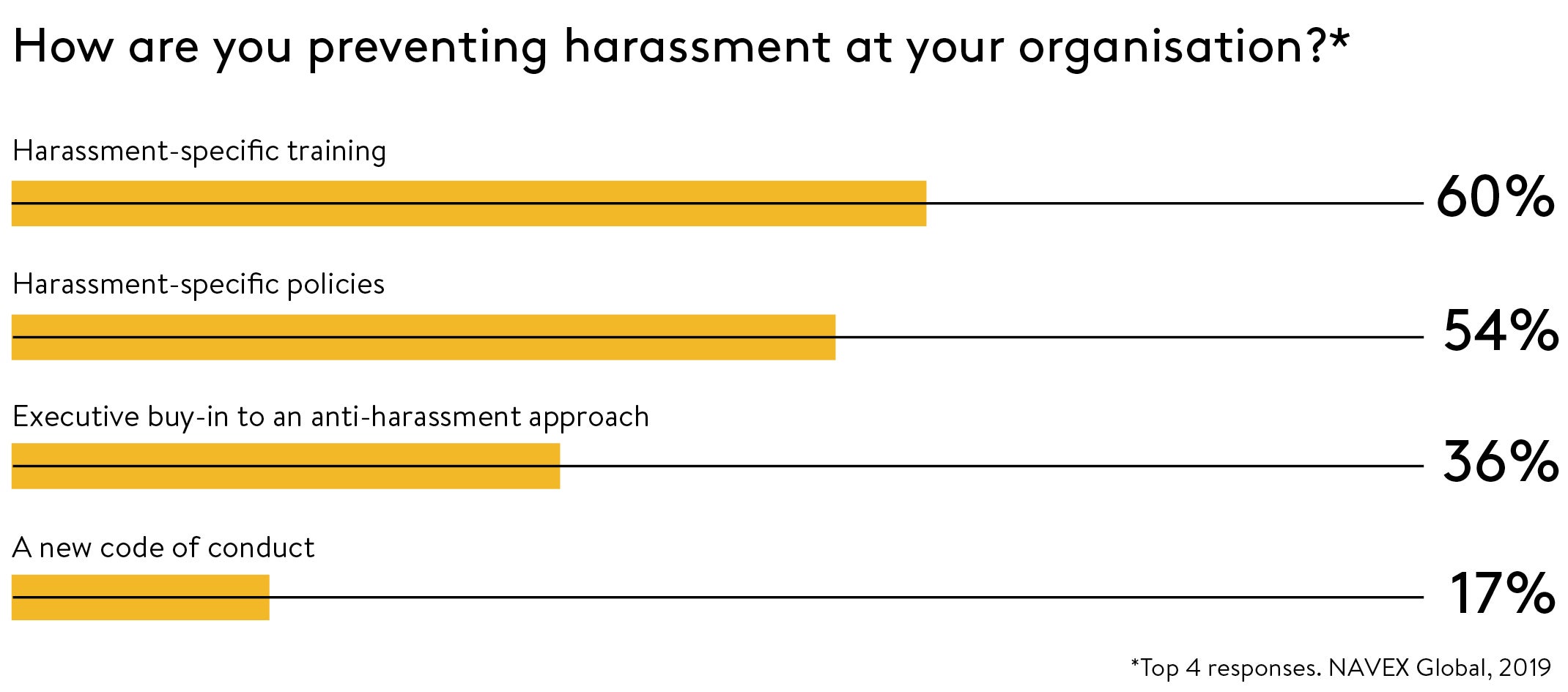

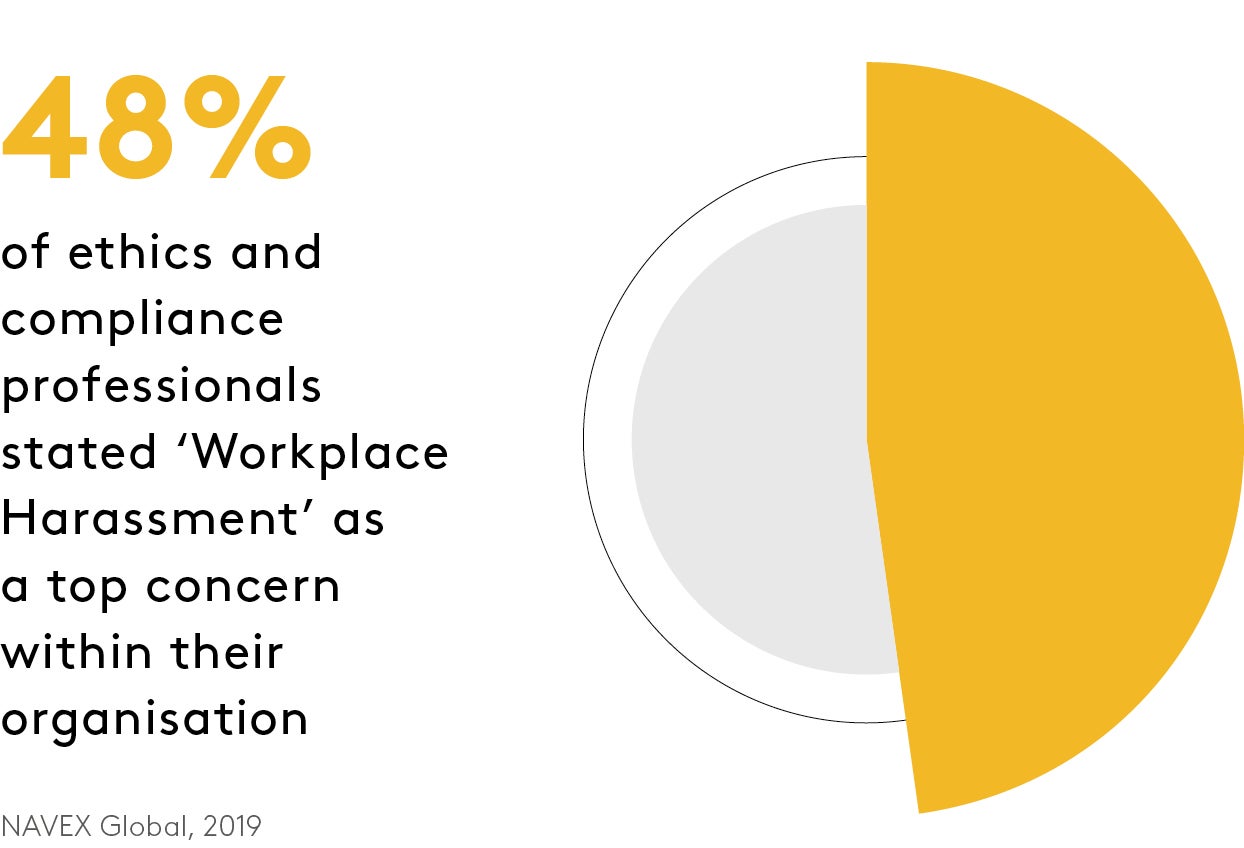

Are organisations investing in the right training and are all staff, including the C-suite, being given the appropriate guidance? It is important to train all staff on how to recognise and deal with instances of sexual harassment.

“We often talk about victims and perpetrators,” says Ms Grant-Hart. “But there’s a huge amount of training to be done around bystanders. What should they do when they see inappropriate behaviour? How should they react to sexist jokes? What should they say? How should they report it?”

Some companies include bystander behaviours in their training, but focus only on racism and homophobia. Sexual harassment is often seen as too hard to define and therefore often neglected. “This is a cop-out,” she says, “bystander education needs to be provided.”

There will be differing interpretations of what constitutes sexual harassment within any organisation. “A lot of sexual harassment can be subjective,” says Philippa Foster Back, director of the Institute of Business Ethics. “A hand on the knee can be offensive to some, but innocuous to others. It means the line can be hard to draw and that is particularly true around office banter.”

A survey by law firm Allen & Overy found 80 per cent of respondents thought they could easily tell the difference between banter and harassment, but revealed profound differences in judgment. For example, displaying a calendar with a semi-naked model split respondents 46 per cent who disapproved to 42 who thought it permissible.

The challenge is how to create a common harassment policy across multiple geographies where standards may vary. “It’s a real difficulty,” says Ed Mills, head of employment at law firm Travers Smith. “You can’t always impose total uniformity. The best companies have a generic global policy, setting out core standards. Some may then apply local variations, in line with local laws and customs. Managers may also need to be trained to understand regional attitudes.”

We often talk about victims and perpetrators, but there’s a huge amount of training to be done around bystanders

Kirsty Grant-Hart of Spark Compliance Consulting

3. Ignoring lessons learnt

Legislation on sexual harassment varies globally, but there’s a clear trend. Progressive US states tend to pioneer new standards and the rest of the world follows. This is set to continue in 2019, says Ms Grant-Hart.

“New York is now requiring sexual harassment training for all employers,” she says. “California used to mandate training for companies with more than fifty employees, now it is five”. The training must also be interactive, so that questions can be asked. “It’s proper training, not just box-ticking. The gold standard is now in New York and California, and we can expect companies and jurisdictions to follow their lead,” says Ms Grant-Hart.

The UK in particular tends to draw lessons from America. The UK Equality and Human Rights Commission is developing a code of practice for employers on sexual harassment. It is expected to address issues such as non-disclosure agreements and confidentiality clauses by employers when settling cases, helping to improve regulation of internal investigations.

4. Overlooking rehabilitation

While many businesses aspire to a zero-tolerance policy around forms of harassment, sacking workers for minor misdemeanours is not always necessary or desirable. In 2019, we’re likely to see a continuation of opting to educate and reform offenders. Chelsea Football Club, for example, has taken the decision not to ban fans immediately for using anti-semitic abuse.

“If you just ban people, you will never change their behaviour,” says chairman Bruce Buck. “In the past, we would take them from the crowd and ban them, for up to three years. Now we say, ‘You did something wrong. You have the option: we can ban you or you can spend some time with our diversity officers, understanding what you did wrong’.”

Companies are now looking for more educational ways of reforming bad behaviour, in the hope they engender changes in behaviour. “We had a client recently with a manager who’d made lewd remarks to a female colleague,” says Mr Mills of Travers Smith. “Rather than sacking, there was mediation. We gave training, he ate humble pie and learnt better behaviour. It’s part of a trend for being more creative in the way issues are resolved.”

Quiet reflection will play a role. It helps to take the time to be more self-informed, rather than opinionated

Philippa Foster Back, director of the Institute of Business Ethics

5. Lack of due diligence

Another red flag is emerging within mergers and acquisitions (M&A), where failing to carry out proper due diligence on third parties and senior employees can come back to haunt your brand, even if incidents technically occurred outside your own organisation.

In response, related policies are gaining clearer legal definition. M&A activity in the United States is now incorporating a clause regarding sexual harassment, known colloquially as the ‘Weinstein clause’. Although, movie mogul Harvey Weinstein denies all allegations of sexual harassment and the nomenclature is regarded as unfair by some legal commentators.

Buyers negotiate a right to damages if information comes to light post-deal which materially affects the value of the investment. In some cases, money has been put in escrow to accelerate the resolution of post-deal #MeToo claims. This is particularly relevant in M&A where there is a narrow number of key personnel such as co-founders whose reputation is inextricably associated with the brand.

6. Not prioritising workplace inclusivity

Some companies are failing to ban practices that would have raised concerns in the 1950s, but 2019 is the year where remaining unreformed corporate habits look like being exposed and addressed. For example, a well-known footwear brand recently announced it would no longer allow employees to put ‘entertainment’ trips to strip clubs on business expenses. They emailed employees in November, declaring it was ‘committed to providing a respectful and inclusive workplace’.

Creating more positive spaces for female inclusivity is especially important in the workplace as research has shown offices where there are fewer women than men often have a higher incidence of sexual harassment. According to a Pew Research Center survey, half of women who say their workplace is mostly male (49 per cent) say sexual harassment is a problem. However, only 32 per cent say the same from women who work in mostly female workplaces.

7. Forgetting transgender rights

Harassment is experienced by people of all types of sexuality, by both women and men, and by transgender individuals. The good news is that acceptance of transgender rights has risen remarkably in the past few years. For example, the British Army is now an enthusiastic promoter of transgender soldiers, stating: “The Army welcomes transgender personnel… all who apply to join the Army must meet the same mental and physical entry standard as any other candidate. If you have completed transition, you will be treated as an individual of your affirmed gender.”

However, workplaces may find it hard to achieve unanimity on acceptance, including around issues such as bathroom rights. The solution? “Quiet reflection will play a role,” says Ms Foster Back at the Institute of Business Ethics. “It helps to take the time to be more self-informed, rather than opinionated. Do research, on both sides of the argument, so you are better prepared to have that discussion. Polarised debate, promoted by an often irresponsible press won’t help.”

The key for businesses is to ensure discussions are based on respect for all parties involved, to nurture an environment of mutual understanding and protection.

For more information please see NAVEX Global’s Best Practice Checklist: Investigating Sexual Harassment

1. Lack of meaningful data