The first independent governance committee (IGC) reports for workplace pensions as required by the recently introduced Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) rules appeared in April.

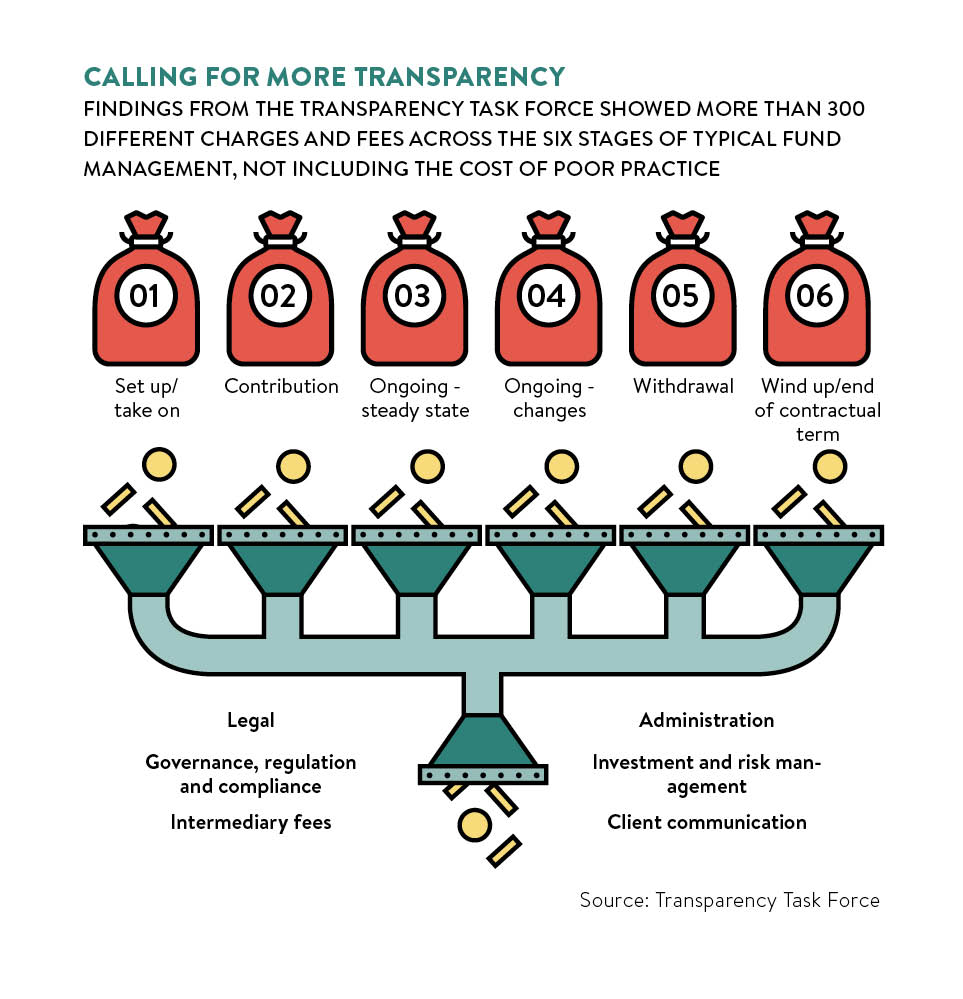

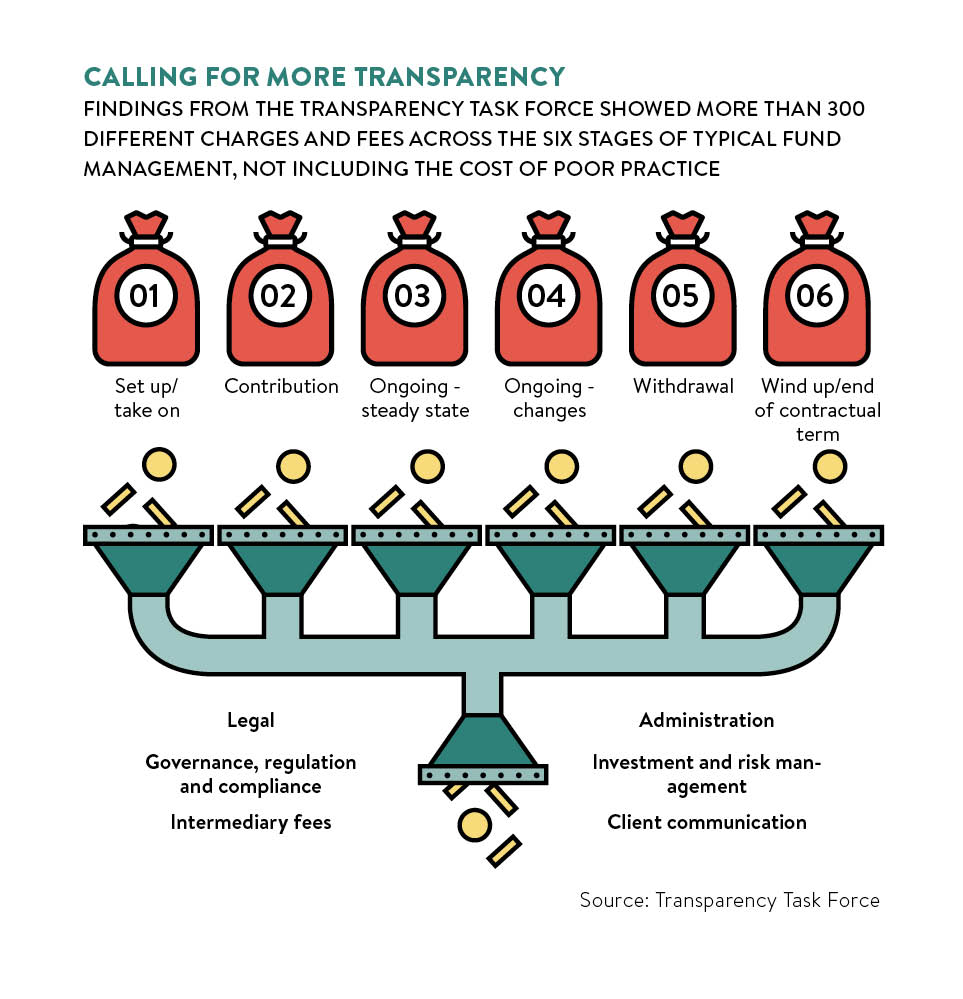

Under new FCA requirements, IGCs are now required to consider whether costs and charges made to workplace pension schemes are appropriate. The mass-release of the new reports, therefore, was the latest chapter in the regulators’ drive for transparency in workplace pensions.

The transparency narrative has not purely been the preserve of the regulators, however. In recent years, trade bodies, consultants and fund firms have all realised they need to do more to make the end-stakeholder more comfortable with what they are paying for.

Getting a better deal

Andrew Pennie, head of pathways at Intelligent Pensions, says cost and transparency have long been on the agenda, but never more so since the launch of the pensions freedoms.

He explains: “Gone are the days when product providers are able to retain or generate income from fund-manager charges – product and fund-manager charges are now very separate, and pricing of the two elements must be clear and transparent.

“Since the changes, I think it is fair to say that product charges have been squeezed more than the fund-manager charges and we are now seeing product costs at significantly lower levels as providers attempt to grab assets on to their books.”

While transparency may have forced fund managers and product providers radically to review their own business operations, it does mean pension savers are more likely to get a better deal.

Regulatory developments in recent years, such as the Pension Regulator’s Defined Contribution (DC) Code, the FCA/Department for Work and Pensions’ call for evidence on transaction costs and the Retail Distribution Review before it, have all played their part.

James Redgrave, director of retirement at Strategic Insight, says: “The government, so by extension the relevant regulators, has put significant recent pressure on fund managers and pension providers to reduce management and other fees.

“This has taken a number of forms, including the ongoing Financial Conduct Authority Asset Management Market Study consultation, but most obviously in the pensions space, the cap on charges for workplace scheme default funds. The focus on default funds is a product of the shift in consumers’ saving behaviour from using defined benefit to defined contribution vehicles.”

Tom Barton, pensions partner at Pinsent Masons, agrees, noting that the momentum we are now witnessing on transparency is the “culmination of a lot of strategic work”.

Getting hold of information about transaction costs has been a challenge, fuelling greater calls for disclosure

He says: “We can track much of this back to the policy of auto-enrolment. Having decided to enrol the workers of UK plc into, overwhelmingly, DC pension schemes with default investment, it seems only right that we make sure those workers get value for money.

“That’s exactly what the regulators and the policymakers concluded as a result of a workplace pensions market study in 2013.”

Despite the progress, Mr Barton admits that trustees and other bodies have sometimes struggled to identify all member-borne costs in workplace DC schemes.

He explains: “Getting hold of information about transaction costs has been a challenge, fuelling greater calls for disclosure and being one of the drivers for the current FCA Asset Management Market Study.

“The study creates a momentum of its own, and the final report will be published at the same time as a wholesale review of auto-enrolment and DC scheme costs – on the cards for 2017.”

One of the most vocal proponents for greater transparency has been Daniel Godfrey, once the chief executive of the Investment Association. He left the role in October 2015 and is now working on the other side of the fence as a consultant to the FCA.

[embed_related]

During his tenure as Investment Association boss, he had lobbied for the membership to embrace charging structures “in pounds and pence”. This, along with some of his other initiatives, didn’t sit well with some members. One senior fund manager, quoted at the time by the Financial Times, said there were “other, bigger issues out there”.

Despite this, he was successful in getting member firms to sign up to a statement of principles in which fund firms pledged to offer greater customer transparency and justify how much they paid their fund managers.

The resistance that Mr Godfrey faced in some quarters is telling, however, and forms part of the reason why trustees do not always trust the fund firms with whom they work.

Revealing costs

Mark Nicholl, partner at Lane Clark Peacock, says most fund managers now routinely disclose the ongoing charges figure – or OCF – but warns that those who do not will soon see business levels impacted.

He says: “Most pooled funds now disclose both the annual management charge as well as the OCF – the fee paid to the manager plus costs incurred in running a poled fund.

“More clients are becoming frustrated that managers are not disclosing useful, reliable information to assess the level of transaction costs.”

Stephen Budge, principal (DC & Financial Wellness) at consultants Mercer says that the solution lies in ‘engagement’.

He says: “We are engaging with managers and asking them to provide some information on our interpretation of explicit costs, that is physical costs relating to accessing markets, rather than the implicit ‘soft’ costs relating to how a portfolio is managed.

“Managers are typically receptive to providing this information, some opting to provide an estimate. We believe this is the only course of action and our clients are supportive of this, until further guidance is available from the FCA or other body.”

Holly McKay, a former asset management firm employee and founder of Boring Money, says the solution is much simpler. “We need to play with a straight bat,” she says. “We’re all a bit fed up of 100-page PowerPoint presentations banging on about alpha in increasingly complex asset classes and structures. Most of us just want a bit of exposure to capital markets at a fair, easy-to-understand fee.”

Shifting to ethical behaviour

Both the FCA and the Pensions Regulator have committed to driving the transparency agenda forward, but some believe the responsibility now has to go beyond regulation and comes down to a simple ethical behavioural shift.

Helen Ball, partner and head of DC at Sackers, says: “It requires a behavioural change, which means all parties need to pull in the same direction. The requirement to explain what member-borne commission payments are for future contracts will help, but we are still waiting for news about what will be done with pre-April 2016 contracts. This is just one small part of the fees/costs project.”

Ms Ball also flags ongoing initiatives with industry bodies, such as the Investment Association, which has established an independent panel to advise on next-generation disclosure for investment costs.

And, despite the advances in transparency in recent years, there is more to be done. The 75bps (basis points) charge cap on default funds and the ongoing exit-charge consultation are among the initiatives that have received widespread praise, but do they fundamentally resolve the issue of opacity?

Not quite, according to Intelligent Pensions’ Mr Pennie. He believes the issue of transparency is much wider.

“While these actions have been positive, I think the regulator and government are really missing a trick in what will actually drive good retirement outcomes for people,” he concludes. “While cost and transparency play a part, they are only a small piece of the equation. I would much rather pay more for a well-performing fund than own a poor-performing cheap one.”

Getting a better deal