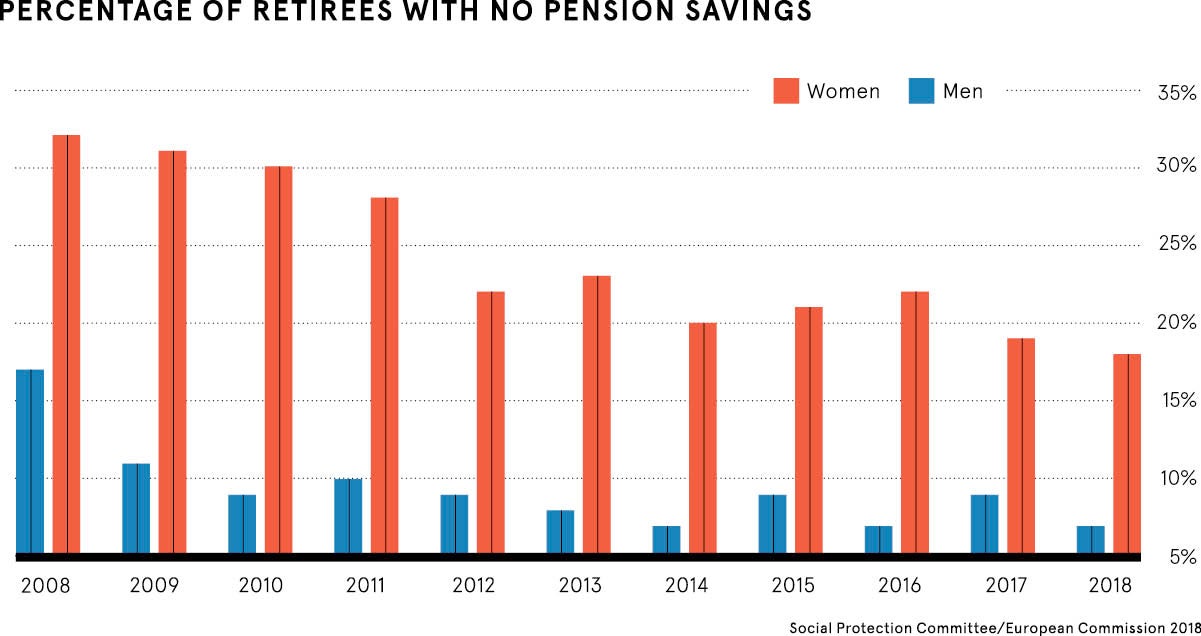

Poor access to company pension schemes is the biggest cause of gender inequality in retirement income, according to a European Union report. Workplace schemes are often not female-friendly or available to large numbers of female workers, particularly the lower paid. This means the gender pension gap, which is twice as bad as pay inequality, could widen as more people rely on workplace schemes.

The findings, from the EU’s Pension Adequacy Report 2018, came amid a spate of headlines highlighting disparities between men and women in workplace pensions.

In the UK, the High Court ruled that guaranteed minimum pension (GMP) payouts should be equalised at Lloyds Bank, a move that could cost other companies up to £15 billion, according to consultants Lane Clark Peacock.

What is causing the gender pension gap?

Meanwhile, pensions expert Ros Altmann sparked a widespread debate by calling for urgent measures to address the “wide gap between men and women in pensions”. She said companies discriminate against women because their pensions suffer from lower earnings, interrupted careers and caring duties.

Ms Altmann suggested helping women retain pension membership during maternity leave or childcare and encouraging employers or partners to contribute for them during breaks could address the gender pension gap.

She proposed removing the UK’s £10,000 earnings limit for auto-enrolled pensions, which excludes millions of lower-paid workers.

Ms Altmann also called for a ban on companies placing workers into arrangements with so-called net pay rules. These often force low earners to pay 25 per cent more than other workers for workplace pensions, she said.

But Rosie Lacey, pensions manager and member of the Pensions Management Institute advisory council, says the term “discrimination” is controversial in all these issues.

“Newspapers said the GMP rules were discriminating, but I don’t think they were,” she says. “Under the previous GMP rules, men suffered more initially than women; the advantage, in most cases, swapped from women to men over time. Equalising could just as likely be in men’s favour depending on their life stage. But I nonetheless welcome the ruling as it clarifies a complex issue.”

Gender pension gap is a major issue across the EU

Ms Lacey also says all the issues about lower-paid workers raised by Ms Altmann apply equally to men and women in the same situation, so they are not discriminating against gender. She says the comment referring to maternity breaks applies to final salary schemes, which do retain pension membership for women who take a break.

However, Ms Lacey still agrees with most of Ms Altmann’s proposals. They would help both men and women and, since more women are lower paid, they would help close the gender pension gap, she says.

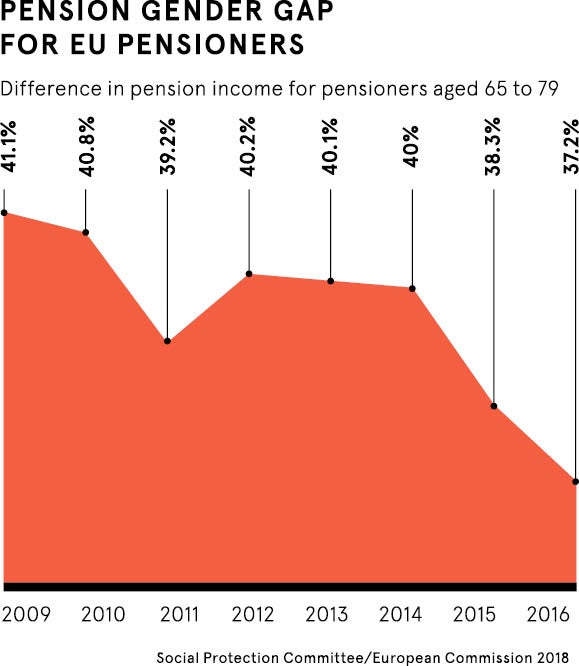

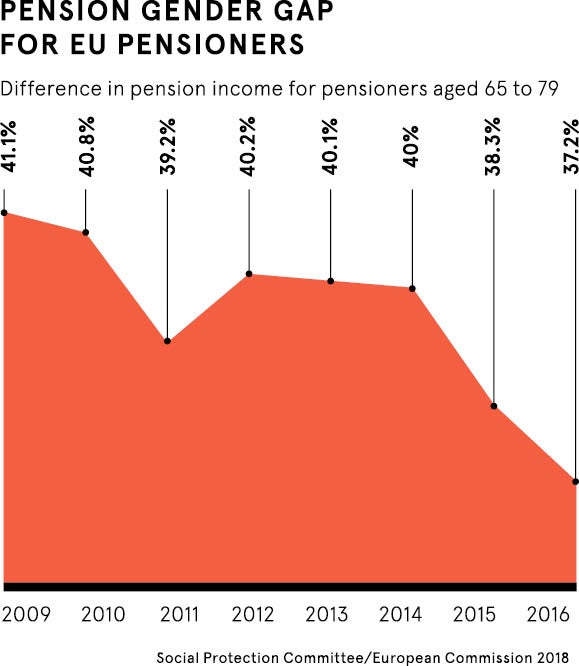

The gender pension gap is a persistent problem in the UK and in many other countries. The EU report shows that the average difference between men’s and women’s retirement income in member states is 36 per cent, more than twice the 16.3 per cent pay gap.

This mostly reflects pay inequalities, which lead to shortfalls in lifetime earnings, a lack of mitigating design features in pensions, and women having more part-time jobs and career breaks, the report says.

We are working to equalise the career gap. Like many companies, we face a diversity challenge and genders may not have equal careers

What can be done to address the gender pension gap?

Research by insurer Aviva suggests the gender pension gap amplifies the pay gap, partly because of behaviour. For example, women tend to choose less risky investments, which grow less over time. Better advice to employees could address this.

But access to company schemes is the biggest issue, according to the EU report. It says: “Where occupational systems are common, access to [them] eclipses all other considerations in entrenching gender inequality. As these types of pensions spread, more inequality may be created.”

According to a separate report from the European Parliament, in addition to improving access, schemes could become more female friendly by offering care credits, better widow’s pensions and measures to improve financial literacy. The growing role of occupational pensions also calls for more stringent regulation to prevent inequality, it says.

The UK has closed its gender pension gap from 44 per cent to 34 per cent between 2009 and 2016. However, the gap is below 10 per cent in Estonia, Denmark and Slovakia.

In poorer countries, this could be due to women needing to work longer and take fewer career breaks. However, Denmark could be an example to other developed countries. It has targeted the gender pension gap since 2005 with initiatives including education to address gender segregation, for example though women’s career choices, laws and initiatives to address the gender pay gap, and interventions on parental leave and care services to support female careers.

How UK employers and legislators could learn from the Danish

Lars Green, executive vice president at Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, says Denmark sets labour market conditions via co-operation between government, employers and employees, which has helped close the gender pay and pension gaps.

“Our company takes a similar collective approach,” he says. “It provides regular pensions advice to individuals, which helps reduce the gap. We have equal pay and pension contributions for equal roles. But we are working to equalise the career gap. Like many companies, we face a diversity challenge and genders may not have equal careers.

“So we aim to have more women in all organisational levels, especially senior roles, through programmes to encourage female talent and to address managers’ potential unconscious biases.”

Maj Britt Andersen, senior vice president of Danish brewer Carlsberg, says closing the gender pension gap is about organisational culture. “We may have set a standard [in pensions equality],” she says. “We say that Carlsberg was probably the first company in the world with a corporate social responsibility policy. But it was more likely [due to] the founders’ mentality of treating people equally.”