To tweet or not to tweet, that is the question. This is perhaps Tesla supremo Elon Musk’s soliloquy of late. It’s almost Shakespearean in its drama. Was it nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows pitted against Tesla’s outrageous fortune or to take arms against the US authorities in a sea of troubles?

This is not to rewrite Hamlet, but rather to highlight a questionable tweet the charismatic boss made about taking electric car firm Tesla private. The US regulators accused him of misleading investors and sued for $20 million. He must now relinquish his role as chairman for three years. Perchance to dream in public no more. Mr Musk’s wings as an outspoken chief executive could be clipped, at least for now.

Companies shouldn’t be about the cult of the individual and must go beyond the life of any single CEO

“Charisma is an important component of effective leadership providing reassurance to stakeholders that people like Musk will make a vision happen and ensure an organisation like Tesla is agile. But charisma isn’t the be-all and end-all,” says John Antonakis, professor of organisational behaviour at the University of Lausanne’s business school. “Mr Musk behaved in ways that are not appropriate for a person of his status. This raises questions as to his credibility and creates uncertainty.”

Why the board must be able to curb charismatic founders

Not to mention a media frenzy, share price volatility and speculation. So much so that the furore has raised issues for future chief executives and boardrooms.

That’s because Tesla’s legal battle signalled a need for more assertive boards and tighter oversight at a time when high-tech unicorns flourish. Corporate governance needs a shake-up. It also needs to be fit for purpose in an era fuelled by social media.

Captivating, yet erratic with an impulsive drive, is not just the hallmark of a visionary Mr Musk, who also runs SpaceX and the Hyperloop Boring Company. Others come to mind, whether it’s Ryanair’s Michael O’Leary, Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook or Martin Sorrell, ex-head of WPP; then there’s the commander in chief and one-time chief executive, US President Donald Trump. With all these strong characters, there’s a question worth asking of accountability.

“In some cases, there is none. It renders the board meaningless, they become a cheering section,” claims Professor Charles Elson, director of the Centre for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware. “You need a strong independent board to counterweight a charismatic CEO otherwise, from a shareholder point of view, it can be a complete disaster.”

The problems surrounding the chief-exec-as-chairman role

It doesn’t help that a fistful of the multi-billion-dollar tech giants have a chief executive who doubles as a chairman. In many ways, this goes against principles of good governance. Now two thirds of OECD jurisdictions encourage a separation of this role, as do emerging market regulators.

“This is a case of US exceptionalism which, from a governance perspective, accentuates the issue of an all-powerful CEO,” explains Alissa Amico, managing director of GOVERN, the Economic and Corporate Governance Centre.

Then there’s the issue of dual-class shares, where the stock is split into different categories, giving owner-chief executives preferential rights. It allows company chiefs, as minority shareholders, to retain control. For instance, Alphabet, Google’s parent, is structured this way, so is Facebook, while Mr Musk owns more than 20 per cent of Tesla’s equity and voting rights, not forgetting similar situations at Apple, and China’s Alibaba and Tencent. Tech companies are rife with complicated governance.

“We need to bring back one share, one vote and eliminate these structures. It creates a complete disconnect between shareholders and the company, leading to problems. The chairman also needs to be independent and a non-executive,” says Professor Elson. “Companies shouldn’t be about the cult of the individual and must go beyond the life of any single CEO. The boss must also be held to account with the same standards as any other worker.”

Social media is a dangerous playground for CEOs

Entrepreneurial, tech company founders insist these structures enable them to make agile decisions in rapidly evolving markets, even though they’re unpopular with investors focused on the vagaries of quarterly earnings reports. Those opposed say it erodes the integrity of markets and allows autocratic bosses to run roughshod over shareholders.

It’s why companies with multiple share classes can no longer join the S&P 500 or the FTSE Russell and comes after Snap, the messaging app, offered stock with no voting rights at its initial public offering. On the other hand, tech monoliths with limited governance structures tend to be so successful.

“With the meteoric rise of companies and their CEOs in this digital age, there has unfortunately been an absence of educating the leadership,” says William Klepper, management professor at Columbia Business School.

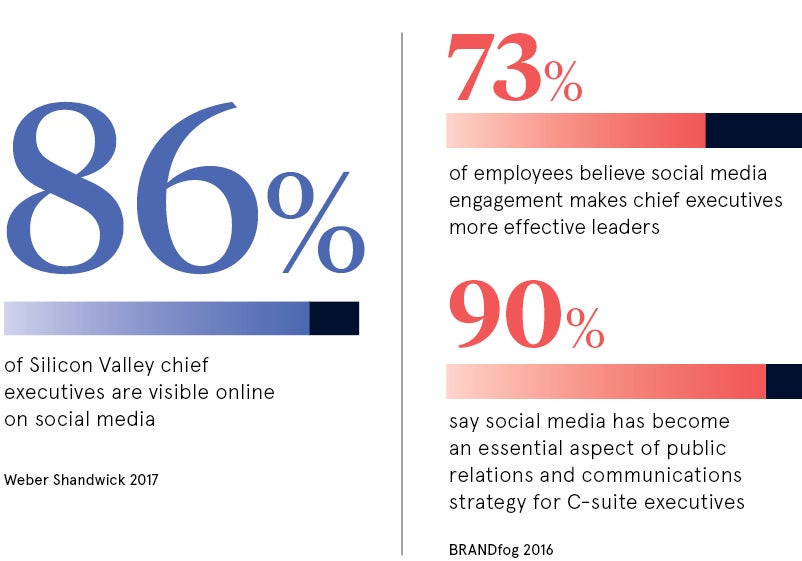

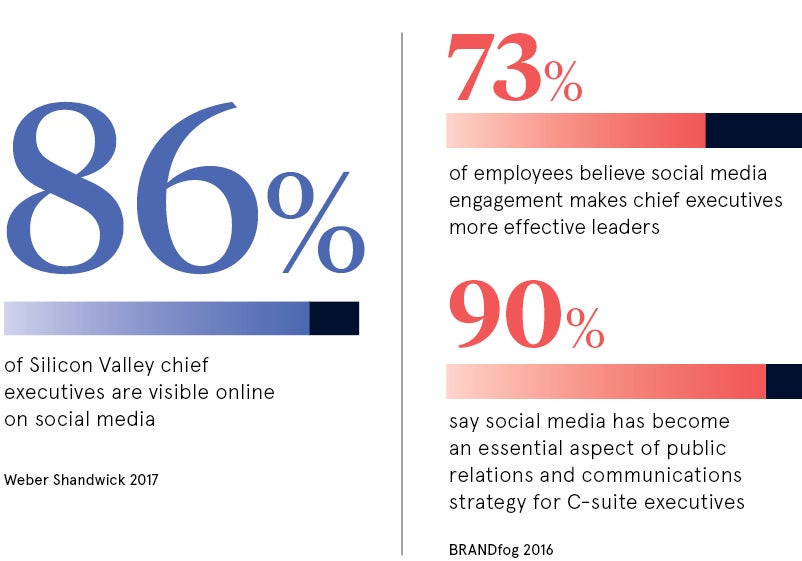

Sharon Sands, global lead for development at Heidrick & Struggles, adds: “Social media feeds the ego and is a dangerous playground for CEOs, so it needs careful thought. Fortune 500 companies on Twitter tend to be carefully managed by a team of experts.”

Good governance: how the board can hold CEOs in check

Audit committees, which are lacking in some companies, can also do a good job of overseeing compliance, including holding maverick chief executives to account. Yet there’s a broader issue here. Perhaps the traditional board isn’t fit to manage 21st-century bosses.

“The skillset needs to change,” says GOVERN’s Ms Amico. “Boards used to be about traditional business strategy and financial oversight. The question is whether they’re now equipped with the right skills to have a meaningful conversation with the CEO. Board members need to be on the cusp of the latest thinking with technical skills in artificial intelligence or blockchain, for instance, which is still rare.”

Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet holds a human skull while reciting: “To be, or not to be…” In a modern-day company drama, perhaps it would be a visionary chief executive with the head of an ineffective board member.

Why the board must be able to curb charismatic founders

The problems surrounding the chief-exec-as-chairman role