Prosthetics have made extraordinary advances in recent years and are changing people’s attitudes to disability. Stellar performances by elite disabled sportsmen and women earn the admiration of millions of fans and also give a glimpse into how quickly technology in prosthetics is changing.

Artificial arms and legs have become highly functioning, lighter, faster and more efficient. State-of-the-art prosthetics can look like something out of a sci-fi movie, incorporating the latest technology that enables users to live life as fully as possible.

Bionic arms use electricity and robotics to create movement, with muscle sensors connected to skin that enable the user to operate the limb effectively. Nerve detectors can be used to control the prosthetic, helping it to move freely and not limited to a small number of movements.

But while advances in robotics and computing power are transforming prosthetics, the limitations of NHS procurement mean the best products are rarely available to NHS patients. The vast majority of amputees do not have access to the technology or the expertise needed to fit them and to ensure they continue to function as they are intended.

The cost of modern prosthetics is a significant barrier, although prices are coming down as adaptation grows, particularly with increased use of 3D printing to produce limbs. In addition, lifetime economics need to be factored in, as next-generation prosthetics enable amputees to lead fuller and more productive lives and to remain healthier.

However, the NHS is unable to commission many of the latest prosthetics. For example, the Hero Arm designed and manufactured in Bristol by Open Bionics, is available to children in France and the United States, but not in England unless their families pay for it themselves.

Samantha Payne, co-founder of Open Bionics, says: “We recognise that NHS clinicians want to give the best technology to their patients. The problem exists at commissioning level. The current commissioning arrangements were put in place before bionic technology existed and haven’t evolved.

“It is frustrating because we worked for five years with the NHS in the development of the Hero Arm with the NHS price point in mind and we reached that point.”

Ironically, development of the Hero Arm was supported by a contract with NHS England that used SBRI Healthcare, part of the Innovate UK Small Business Research Initiative, which helps innovative businesses work with big public sector organisations to implement new technologies.

Earlier this year Open Bionics raised £4.6 million from investors, which included the Williams F1 team’s Foresight Williams, Downing and Ananda Impact Ventures. This will support Open Bionics to scale up its manufacturing capabilities to serve the UK and overseas markets, including the United States.

Yet even as this pioneering company looks to expand abroad, the reality is its products and others made by companies in the UK remain unavailable to amputees through current NHS procurement arrangements.

NHS prosthetics services are currently under review, which could give the opportunity to make the transformation that many amputees believe is needed. However, NHS England has been clear that one of the main reasons for the review is to “ensure that we achieve maximum return from every pound spent”, raising fears the review is about containing costs and not about quality.

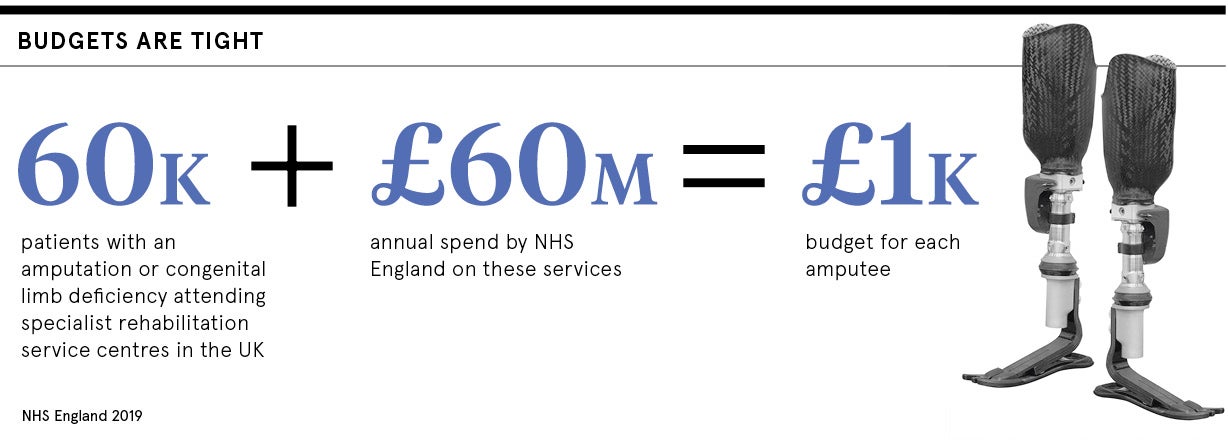

The number of patients with an amputation or a congenital limb deficiency is now estimated at around 60,000 and NHS England spends about £60 million a year on specialist rehabilitation services.

There are 35 centres in England that provide specialist prosthetic services. These are consultant-led services and they involve a specialised multi-disciplinary team, which includes, for example, a prosthetist, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, podiatrist and psychologist.

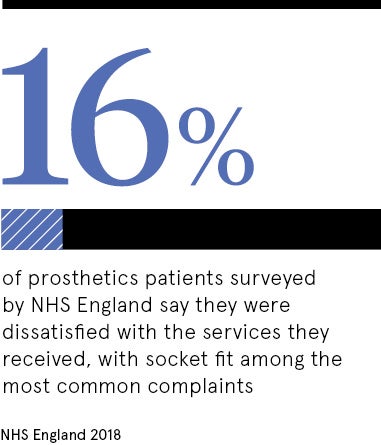

As part of the review, NHS England carried out a three-month consultation with service users, receiving almost 900 responses. It is a snapshot of the postcode lottery of access to more advanced artificial limbs and levels of support.

Socket fit was raised as one of the most common complaints. Several people commented there should be an attitude of “getting it right first time” with reported delays, unnecessary multiple appointments and waits before issues were resolved. Delays have meant that by the time the socket is ready, there have already been changes to the stump in the meantime, which is not uncommon for new amputees or people who are left inactive and gain weight.

In recent years there has been a shortage of technicians with the expertise to make sockets, says Gordon McFadden from the charity United Amputees. As hundreds of ageing but highly skilled prosthetists retire, they are being replaced by less experienced staff. The number of orthotists and prosthetists, already small, is in decline, according to the latest figures from Health Education England.

During the NHS consultation, many patients expressed frustration that they could not top up their NHS funding to buy bionic limbs privately, which is not an option under current arrangements. Crowdfunding has become an important means to raise money to access state-of-the-art artificial arms and legs not available through NHS procurement channels.

Gemma Turner, from Calderdale, West Yorkshire, turned to GoFundMoney to raise the £25,000 needed for a prosthetic limb for her son Jacob. He was born eight weeks premature without his left arm.

“Unfortunately they don’t offer the type of prosthetic Jacob needs in the UK, so we’ve had to look elsewhere,” says Gemma. Their hope is a company in New York, A Step Ahead Prosthetics, established as one of the world’s leading providers of prosthetic care.

Meanwhile, patients in England await the outcome of the review of prosthetics services, which is due later this year. But NHS England warns: “Some of the changes required will take some time to realise, as we will need a totally different approach to the way services are paid for and we would not want to rush into plans that could destabilise services or disrupt patient care.”

The challenge of the next few years will be to ensure the next generation of prosthetic limbs reaches all those who need it, without recourse to charity or public appeals. It is a human right that transcends economic considerations or systemic barriers. Just as we admire the superhuman achievements of Paralympians, we must do all that we can to help disabled people lead ordinary lives.