The NHS is powered by a £117.2-billion budget and more than one million staff, who deal with one million patients every 36 hours and a mosaic of almost 150,000 hospital beds. From the operating theatres through to outpatient units, it is an organisation ripe for transformation.

A host of digital innovation promises swifter, more targeted treatments and better outcomes for patients, but the pace of change is glacial.

More than half (51 per cent) of NHS trusts, which control hospitals and community healthcare, run at a deficit despite making efficiency savings of £2.9 billion over the last year. It is easy to see how the prospect of spending money on digital innovation may get washed away as the NHS creaks along like an old galleon constantly mending leaks rather than stopping for a refit.

The tectonic plates of locked-in delivery practices and disruptive technology are grinding away at each other while the pressure from an ageing population with chronic co-morbidities keeps rising.

Care is being reshaped away from expensive hospital admissions to at-home condition management using wearable technology and remote monitoring. But many innovators are still some distance from satisfying the high requirements of healthcare systems with multiple stakeholders and high data security values.

There are so many areas of the NHS where we don’t know we have a problem

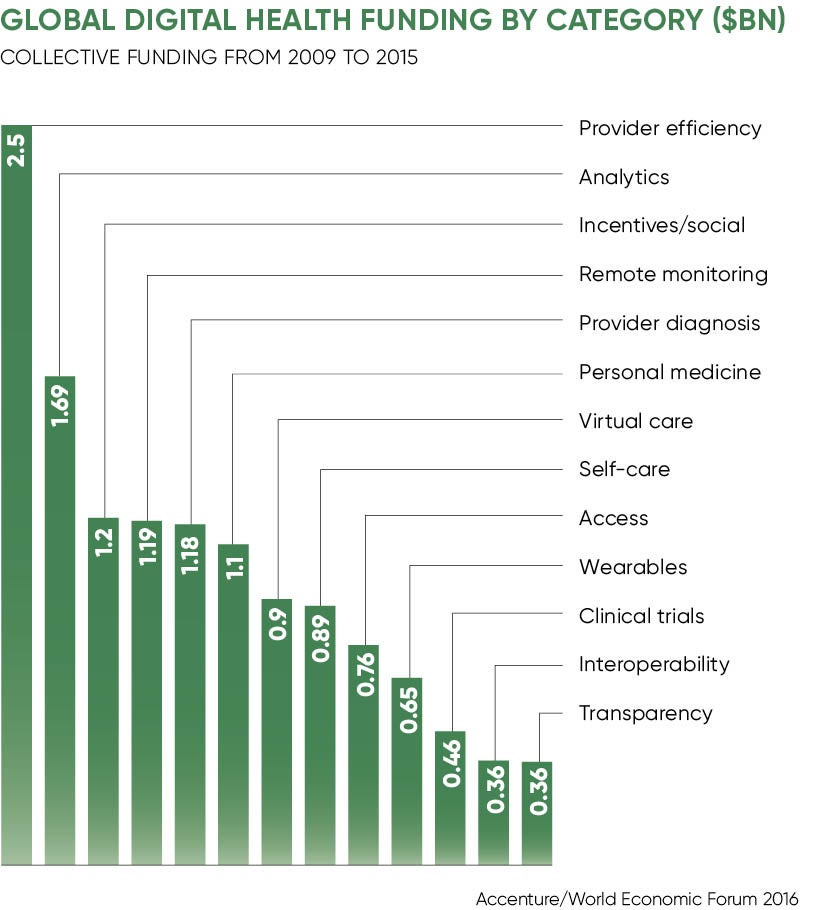

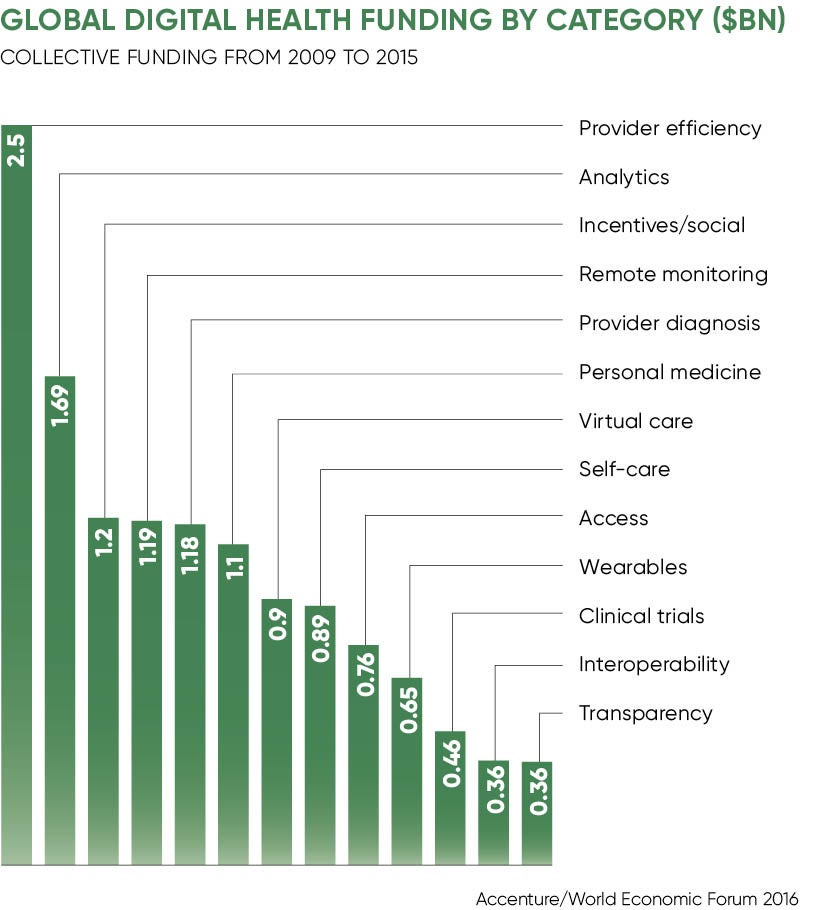

A report for the World Economic Forum by consultants Accenture highlighted the potential gains across anything from genetic sequencing to regular GP check-ups, but warned: “A big gap exists between where chief executive officers are now and where they want to be. More than 90 per cent wanted to change their technology investments or find better ways of harnessing big data, but only a third had actually upgraded their technology or analytics capabilities.”

That view is echoed by Professor Joe Harrison, chief executive of Milton Keynes Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. “The difficulties are obvious,” he says. “The outpatient department where two thirds of patient interactions take place in hospitals is the same now as it was in the 1980s. It is easier for you to book a taxi, hotel and flight to Australia than it is to change your outpatient’s appointment.

“We traditionally throw more people at a problem. As demand has increased over the years we have grown our workforce to the point where I employ more than 100 people here to manage the outpatients’ system.”

Milton Keynes is a single-site 400-bed acute hospital employing 4,000 staff to treat a population of 320,000 and deals with a procession of almost 350,000 outpatients every year.

“There are so many areas of the NHS where we don’t know we have a problem. You have all these brilliant companies out there saying they can fix this or that, but half the time we are not aware we have a problem because we have always done it that way,” adds Professor Harrison. “This is the stuff that banking went through 20 years ago yet we can’t overlay that on our mindset or our ability to deliver within the NHS and it could be worth tens of millions.”

He is fairly typical of chief executives wrestling with pressing budgets, but he has negotiated a trial of the medical booking system Zesty, which has developed a sophisticated app with one million users across the UK and Europe, and a number of partnerships with NHS trusts.

Significantly both its founders, James Balmain and Lloyd Price, come from e-commerce backgrounds and used their business experience to shape how they built a system that delivered efficiency and savings to a healthcare setting.

“We didn’t compromise our products to sync with the NHS, we enhanced them,” says Mr Price, who has worked in online sectors from retail to dating. “The three main areas we had to work on were security, workflows, and winning hearts and minds. The other important factor is the uniqueness of the NHS. You have two masters to serve: the NHS which pays you for the service and the patient who uses the service. It is a challenging business idea.”

The NHS is getting better and the policy direction is to provide more funds for investment in schemes

The Zesty team had to understand the idiosyncratic rhythms of the NHS to ensure its product helped clinicians, nurses and support staff.

“Technology companies need to build products and services that remove friction for the user, the patient, and then create new habits and behaviours so they can adapt to the changes easily,” he adds. “Trust is key to digital transformation within healthcare because the nature of data collected, transmitted and shared in healthcare is very sensitive.”

Earlier failures of big IT projects have created a risk-averse structure riveted by plates of bureaucracy, but Professor Harrison sees progress.

“The NHS is getting better and the policy direction is to provide more funds for investment in schemes such as this,” he says. “It is easy to criticise the NHS, but I don’t think the private sector has been that smart in targeting areas in the system that may have funds. There is little point going to a trust that is under the cosh. Some of their research and understanding prior to a business approach is not consistent.”

Dr Paul Tunnah, chief executive of content and communications company pharmaphorum, which connects the pharmaceutical industry with the broader healthcare ecosystem, says new companies face an uphill struggle to find an access point to the NHS that operates in silos.

But he adds the NHS Innovation Accelerator and other government initiatives are encouraging “a more nimble, digital-savvy NHS to emerge in the face of urgent necessity to manage spiralling costs”.