The coronavirus pandemic is like a black hole, consuming global health resources and the concerted efforts of countless medical professionals around the globe. It’s threatening progress against other killer diseases, such as malaria, HIV and tuberculosis. In the UK, it has had a significant impact on charity-funded medical research, not to mention primary care or cancer treatments. The list is long.

The outbreak has huge ramifications for the future of healthcare, medical research budgets and the focus of funding. “What makes this pandemic unprecedented is not the virus, but the response to it, which is mostly driven by fear and panic that overestimates and overreacts,” says Ade Adeyemi, who heads up the global health fellowship at Chatham House.

“This is causing enormous harm and I think there will be a self-correction in early-2021. The medical community, from fear of losing all their funding to COVID-19, will start contextualising the pandemic and giving a more balanced analysis.”

COVID-19 is diverting funds from other research

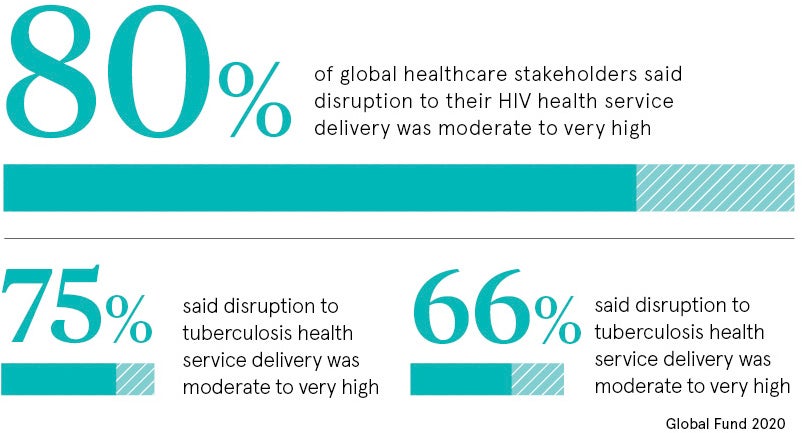

The numbers to do with the COVID-19 black hole are eye-popping. Around three quarters of malaria, HIV and TB programmes in 106 countries have been disrupted, according to a survey by the Global Fund. While in the UK, the Association of Medical Research Charities (AMRC) is reporting a £310-million shortfall in medical research funding, which is a 41 per cent drop.

“It will take over four years for research spending to fully recover, but a decade to rebuild what will be lost in terms of capacity and capability. Many organisations are concerned they will be unable to fund future clinical trials and studies,” says Nisha Tailor, director of policy at the AMRC.

The potential global economic recession caused by the pandemic doesn’t bode well for medical research either. At the same time, global health efforts risk being securitised. This is where health challenges such as the ongoing pandemic are seen as existential security threats to be dealt with along the same lines as terrorism or illegal immigration. Border closures and quarantine rules for travel are part of this process.

“This leads to nationalistic approaches by individual nations rather than global solidarity and cross-border co-operation. It tends to divert the money of wealthier states towards strategies that keep the wealthy safe. Global health challenges in poorer countries and their underlying socio-economic determinants risk being ignored in the process,” says Jens Martens, executive director at the Global Policy Forum.

“The World Health Organization and UNICEF have already warned of an alarming decline in the number of children receiving life-saving vaccines around the world.”

An all-consuming topic for published research

At the same time, COVID-19 has the potential to suck in medical research funding among top institutions around the globe keen to receive fresh support. Already the pandemic has led to the biggest explosion of scientific literature ever. By early-June, more than 23,000 papers had been published, doubling every 20 days, according to one estimate.

“Going forward I expect we’ll see a tendency for grants to mention COVID-19, similarly to how, in the last few years, it’s been fashionable to mention machine-learning in every application for research on genetics,” says Dr Doug Speed, assistant professor at the Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies in Denmark.

Medical research that shows a clear correlation between COVID-19 infections and chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes, both of which impose a huge cost on the NHS, are also likely to garner more interest. In fact, obesity increases the risk of dying of COVID-19 by almost 50 per cent.

“This is likely to lead to further calls on the UK government to fund more programmes to tackle this condition,” says Dr Sabrina Germain, senior lecturer in medical law at City, University of London.

Will COVID-19 reinvigorate health spending?

There’s no doubt COVID-19 is putting public health and spending, or a lack of it, as well as healthcare inequalities, firmly on the agenda of countless politicians and decision-makers globally. It could, therefore, have a positive effect on medical research funding for the long term.

“I personally don’t see a long-term dip in research for other conditions; others may disagree,” says Adeyemi at Chatham House. “Medical issues have never had so many column inches in newspapers, airtime on television or feeds on social media. The health of any nation, and for every generation, is now a daily conversation. This attention could, in turn, give a shot in the arm to underfunded healthcare systems.

“Many people are now aware of the importance of preventative care for reducing exposure to disease. The awareness of how vaccine development occurs has increased and many approve of developing a vaccine for COVID-19, for instance. This has changed the conversation on vaccine acceptance in many parts of the United States,” says Dr Emmanuel Peprah, assistant professor at New York University School of Global Public Health.

Sharpening focus and driving innovation

COVID-19 has also shown what the healthcare profession is really capable of. The pandemic has brought about a renewed and shared focus, driving innovation, accelerating timelines for solutions, streamlining regulatory processes, with a significant increase in collaboration. There’s no going back.

At the same time, the profile of invention has risen to new heights with digital technology topping the list with more virtual health appointments and home monitoring.

“We’ve seen exponential innovation during the first phase of the pandemic. The NHS has made a great leap forward in terms of digital transformation,” says Germain. “The pandemic may also lead to more spending on public health and the NHS, but it is a sector that was already underfunded and needed more support to meet the healthcare needs of the British public.”

There’s also been a shift in mindset away from the real costs of healthcare towards patient outcomes. The daily pandemic roll call of deaths makes sure of that. Sad as it is, this could be a good thing. It reminds us all of the real value of our health.

The coronavirus pandemic is like a black hole, consuming global health resources and the concerted efforts of countless medical professionals around the globe. It’s threatening progress against other killer diseases, such as malaria, HIV and tuberculosis. In the UK, it has had a significant impact on charity-funded medical research, not to mention primary care or cancer treatments. The list is long.

The outbreak has huge ramifications for the future of healthcare, medical research budgets and the focus of funding. “What makes this pandemic unprecedented is not the virus, but the response to it, which is mostly driven by fear and panic that overestimates and overreacts,” says Ade Adeyemi, who heads up the global health fellowship at Chatham House.

“This is causing enormous harm and I think there will be a self-correction in early-2021. The medical community, from fear of losing all their funding to COVID-19, will start contextualising the pandemic and giving a more balanced analysis.”