Kelly Smith visited her GP seven times over six months and had numerous diagnostic tests for vague symptoms that all came back negative. Finally, she was rushed to A&E with suspected gallstones, but a CT scan revealed a suspicious mass that resulted in a cancer diagnosis.

“My symptoms first started in October 2016 when I vomited after returning from holiday in Lanzarote and thought I’d caught a bug on the plane,” says Kelly, a make-up artist from Macclesfield, Cheshire. “Two weeks later I was sick again and started experiencing agonising intermittent abdominal pain, like someone was punching my insides.”

Over the next few months, her weight plummeted from ten-and-a-half to seven stone. “I was skin and bone, felt tired all the time and was going to bed at 7.00pm, the same time as my two-year-old son Finnley,” she recalls.

Kelly Smith was diagnosed with advanced bowel cancer in April 2017

Each time Kelly went to her GP’s surgery she would be referred for a different diagnostic test, for Crohn’s disease, coeliac disease, irritable bowel syndrome and suspected appendicitis. “The GP would organise the test and wait for the results to come back before considering yet another potential diagnosis,” says Kelly, who was just 28 when she was eventually diagnosed with advanced bowel cancer (stage 4) in April 2017.

At the back of her mind is the niggling concern that, had her cancer diagnosis not been delayed, the cancer cells might not have spread to 14 lymph nodes and her liver, and her treatment might have been more effective. “After chemotherapy and surgery my bowel is clear, but there are signs of cancer in my liver and lungs,” says Kelly, whose long-term survival now rests with a new trial combining immunotherapy with a targeted treatment.

Lack of urgent referral routes for vague symptoms

For patients like her, presenting with non-specific but concerning symptoms, the problem with achieving a cancer diagnosis is that there are no established urgent referral routes in the UK. The current GP “gatekeeping” system caters best for patients with red-flag symptoms, explains Dr Brian Nicholson, from the Department of Primary Care at the University of Oxford. So-called red flags include signs such as a breast lump indicating breast cancer or coughing up blood indicating lung cancer.

“These provide clear signals where to perform diagnostic tests, allowing GPs to identify site-specific urgent referral pathways,” says Dr Nicholson.

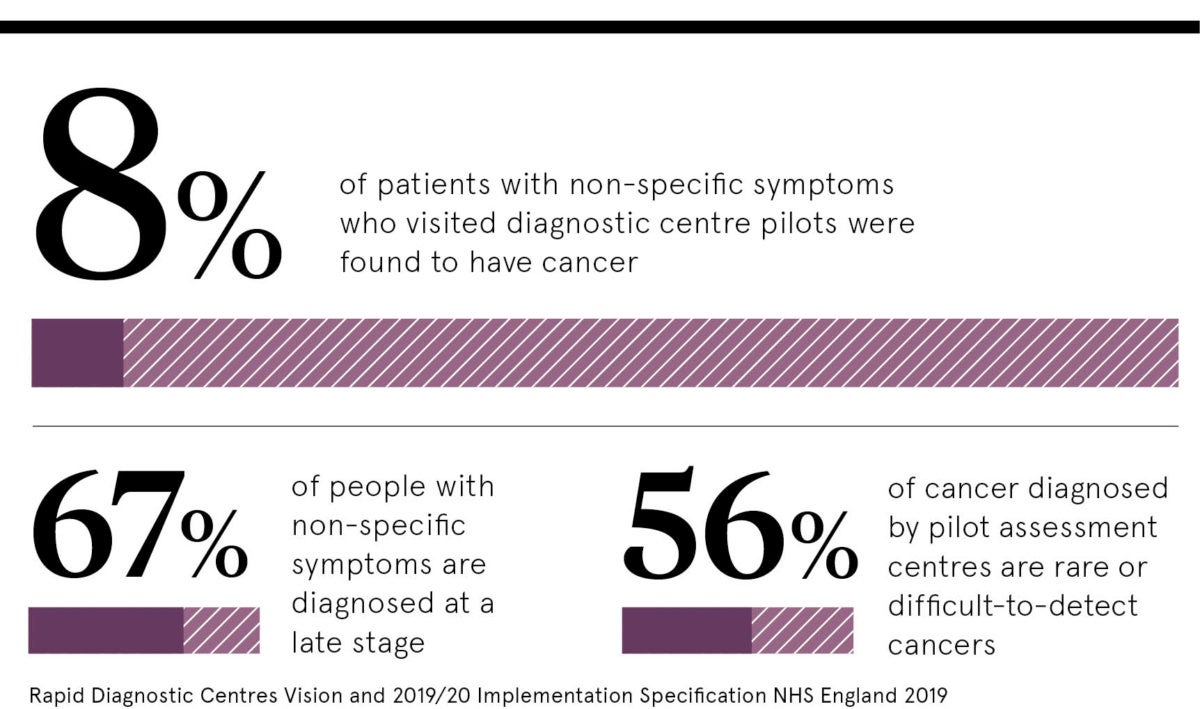

However, studies suggest only half of cancer patients present with classical alarm symptoms. The remainder experience vague symptoms, such as unexplained weight loss and fatigue, giving GPs the problem of deciding which specific pathway to refer them down if they meet the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence two-week urgent referral criteria of a 3 per cent risk

of cancer.

“Anecdotally, GPs refer patients with non-specific symptoms down a number of different pathways, one after another, often leading to significant delays before cancer diagnosis,” says Dr Nicholson.

Data from the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service shows nearly half of cancers in the UK are diagnosed at an advanced stage (stages 3 and 4), and one in five are diagnosed as an emergency. “The higher the stage of the cancer, the greater the chance it will have spread and the more difficult it is to treat, reducing the likelihood of the patient surviving the cancer,” says Sara Hiom, director of early diagnosis at Cancer Research UK.

Delays in cancer diagnosis provide one explanation for the UK’s poor cancer survival record. Last month, a study in Lancet Oncology found that, although cancer survival has improved in the UK since 1995, for the period 2010 to 2014, five-year cancer survival still lags behind six other comparable high-income countries (Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand and Norway) for stomach, rectal, pancreatic and lung cancers.

Piloting rapid diagnostic centres

To address the cycle of patients with vague symptoms being referred for multiple tests and poor survival, the Accelerate, Co-ordinate, Evaluate (ACE) NHS initiative, supported by NHS England, Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support, has been piloting ten multidisciplinary diagnostic centres (MDCs) around the country. The idea is to provide rapid diagnostic centres for non-specific symptoms where tests are co-ordinated to take place where possible on the same day.

A key feature was appointing navigators, who support the patient from the point of referral to discharge. “Standard pathways have specialist nurses who support patients once they’re diagnosed, but patients also need help in the diagnostic part of the pathway,” says Dr Nicholson, who led the Oxford pilot.

The ACE pilots operated in a slightly different ways. For example, at Oxford the navigator was a radiographer, whereas the North Central and East London Cancer Alliance (NCELCA) MDCs in North and East London used a nurse specialist. In Oxford, almost everyone had a CT scan, whereas the London MDCs operated upfront triage to decide who needed scanning. In Oxford patients were seen in regular outpatient clinics, while London scheduled special clinics.

“The aim of all MDCs is to ensure a rapid diagnosis with the best possible experience for patients with non-specific cancer symptoms,” says Dr Andrew Millar, a gastroenterologist at the North Middlesex University Hospital, who led the NCELCA pilots.

Next steps for rapid cancer diagnosis

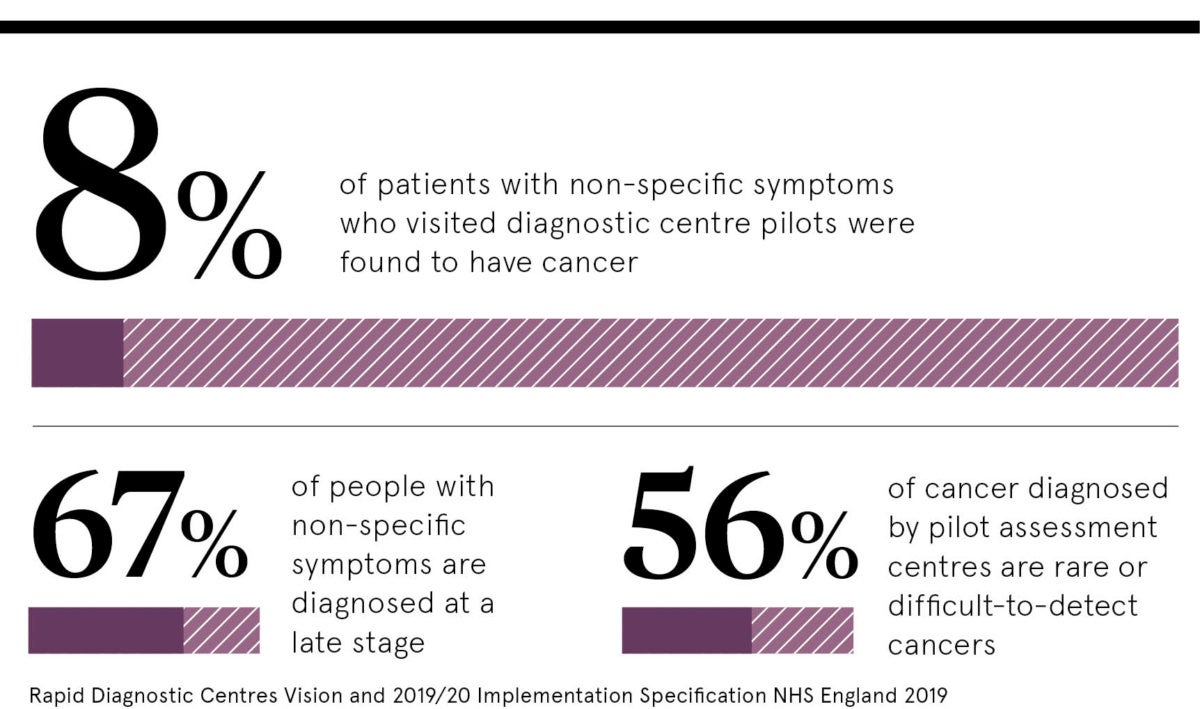

Evaluation of the ten ACE pilots, published by Cancer Research UK in April 2019, showed that between January 2017 and July 2018, 2,851 patients aged between 17 and 97 were referred, with 66 per cent experiencing weight loss, 36 per cent abdominal pain, and 30 per cent nausea and vomiting. Overall 239 (8 per cent) were found to have cancer and more than one third were diagnosed with non-cancerous conditions, most commonly diseases of the digestive system, such as diverticular disease. The model provided a fast route, with a median time from GP referral to cancer diagnosis of 19 days.

The work of the ten ACE pilots has guided the development of a national programme of rapid diagnostic centres (RDCs), which the NHS Cancer Programme and NHS England have announced will start accepting patients in the 19 UK Cancer Alliance geographical areas from January 2020. Over a five-year period it is planned that RDCs will provide a single point of access for all patients with symptoms that could indicate cancer, to support earlier and faster cancer diagnosis.

“Although it will be a challenge to set up services in time, particularly for Cancer Alliances that haven’t had pilots, it is great the NHS is moving quickly to speed up the diagnosis of cancer across the population,” Dr Millar concludes.

Lack of urgent referral routes for vague symptoms

Piloting rapid diagnostic centres