We know the threats. We have the cures. But the chasm between cancer diagnosis and treatment is a deadly stain on the nation’s healthcare record.

Our ability to decode cancer’s multi-faceted jeopardy has outstripped society’s aptitude to modify behaviours and organise the early testing that could mean the difference, quite starkly, between life and death.

Many cancers are detected late into their development when their molecular quirks are causing havoc and a sizeable number are only diagnosed in A&E units when a patient is treated for another condition.

There is a lot more we could be doing to reduce late-stage cancer diagnosis

Cancer screening not keeping pace with cures

Medical science can now sequence a patient’s genome – the individual DNA characteristics that define physical make-up – for less than £500 and immunotherapy can supercharge a patient’s moribund immune system to fight off virulent cancers. Yet the comparatively straightforward process of screening people for treatment is misfiring.

It is now a hot political issue with prime minister Theresa May declaring an ambition to have 75 per cent of cancers diagnosed early by 2028, a jump from the current average of 54 per cent, with almost 5,000 extra staff promised by 2021.

But diagnosing cancer is so unreliable that a climate has developed where legal firms trawl for business by bartering late diagnoses into medical negligence lawsuits.

There are three NHS cancer screening programmes which in 2016-17 identified 460,000 people who needed further investigation or treatment. But Penny Woods, chief executive of the British Lung Foundation, voices concern. “By the time lung cancer causes symptoms, it’s usually too late. That’s why early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for patients with lung cancer,” says Dr Woods.

“Currently, too many patients are being diagnosed via the emergency route, with 35 per cent of sufferers diagnosed in A&E. We’ve seen how successful lung cancer screening pilots have been, where people at high risk of the developing the disease are invited for CT scanning and other lung health checks.”

Pioneering screening programmes can aid early diagnosis

Levels for breast cancer screening are at their lowest for a decade, according to NHS Digital data, while a Lancet report revealed UK cancer survival rates have fallen to the bottom half of world league tables for seven cancers and only come in the top ten for two.

NHS England is now taking screening to the streets, deploying mobile units in supermarket car parks or community centres to change public attitudes.

A pilot programme in Manchester recently scanned more than 2,500 people in three deprived areas of the city, where lung cancer is more prevalent, and discovered 46 cases of cancer. Of these, 80 per cent were early stage one. The scheme, funded by the Manchester Clinical Commissioning Groups and Macmillan Cancer Support, has quadrupled the early diagnosis rates for lung cancer in Manchester.

It is being rolled out to more areas and the results from these one-stop shops, set up in ten areas to catch patients who do not have “alarm symptoms”, will inform a more fluid and dynamic approach to cancer diagnostics.

Work at reshaping techniques is progressing at pace with mobile units using 4G technology to give swift results and synchronise with patient records so people can drop in without appointments.

But a plan to start bowel screening at age 50, following Scotland’s lead, is delayed in England and Wales, and Bowel Cancer UK reported earlier this month that 28 per cent of hospitals in England were in breach of waiting times for bowel cancer testing.

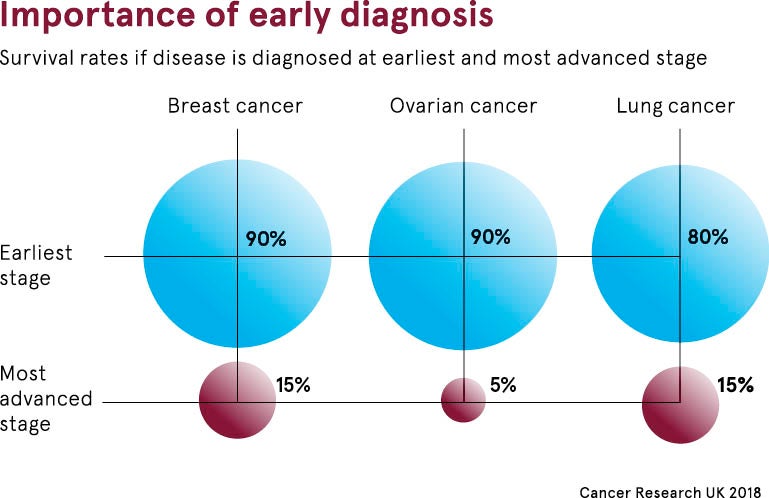

“There is a lot more we could be doing to reduce late-stage cancer diagnosis. We have tens of thousands of people who are diagnosed with stage-four disease where curative treatments are not an option and that needs to be tackled. We should be making progress on this,” says Jodie Moffat, head of early diagnosis at Cancer Research UK.

Using new technology to promote early diagnosis

The government continues to be buffeted by complaints about the devastating consequences of delayed diagnosis and its positive intent faces tough hurdles if it is to revitalise testing while pathology and radiology services are stretched wafer thin.

“It is wonderful to see such high-profile commitment to shifting late-stage diagnoses and getting more people diagnosed early. But it is an ambitious ambition and the government needs to be thinking how it is going to resource its delivery,” says Dr Moffat.

Cancer Research UK figures forecast a rising cancer incidence as the population ages. This could mean NHS England will need to perform 44 per cent more endoscopies than current levels, and train cohorts of experts to deliver the tests and interpret results.

Salvation could come from the use of artificial intelligence, which can spot pre-cancerous patterns from quick body scans and patient data, along with the potential from liquid biopsies, blood tests that pick up biomarkers before damaging cellular changes take place.

Software devised by Japanese scientists has shown it can detect early-stage bowel cancer with 86 per cent accuracy, while algorithms are advancing in prostate cancer.

Collaboration between industry and the NHS could be key

Paul Fitzpatrick, consultant at the Pistoia Alliance, a global not-for-profit life sciences group, believes that industry and the NHS can combine to create a powerful diagnostic and treatment pathway, providing privacy and transparency are enshrined.

“There is a chance to streamline the process so detection is targeted at the right patients, aligning to better treatment options. This will only increase positive outcomes, which will free up resources for the NHS to do other things. This will only work if as a society we’re prepared to share our health data,” he says.

Cancer Research UK’s Dr Moffat concludes: “The research coming forward is hugely exciting. They should help make us better at tailoring services to individual risk and make a significant dent in late stage in the future. At the heart of this is making sure we have a service in which these research advances can be delivered and that will need investments and resources, and require us to think differently.”

Cancer screening not keeping pace with cures

Pioneering screening programmes can aid early diagnosis