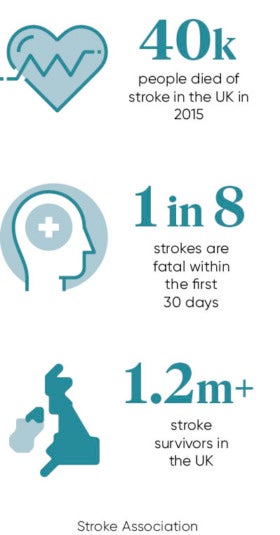

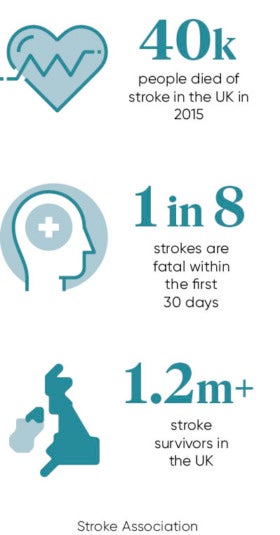

Stroke is a unique condition. It strikes in an instant, but its effects can last a lifetime. It is one of the main causes of death in the UK, killing around 40,000 people in 2015, while many who survive stroke live with severe disability.

Stroke is a unique condition. It strikes in an instant, but its effects can last a lifetime. It is one of the main causes of death in the UK, killing around 40,000 people in 2015, while many who survive stroke live with severe disability.

In recent years, great strides have been made in improving stroke care, which has significantly increased survival rates. But there are growing fears that progress is faltering, and that patients will not benefit from latest advances in care and rehabilitation. This is a particular concern as the existing National Stroke Strategy for England comes to an end in 2017, with no current government plans to renew it beyond this year.

There are more than 100,000 strokes in the UK every year, the equivalent of one stroke every five minutes. And there are more than 1.2 million stroke survivors, but almost two-thirds leave hospital with a disability. So stroke imposes a significant burden on social care as well as on the NHS.

A stroke occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is cut off. The brain needs oxygen and nutrients provided by blood to function properly. If the supply of blood is restricted or stopped, brain cells begin to die. This can lead to brain injury, disability and possibly death. The chance of survival and recovery improves markedly with rapid access to treatment.

Present picture

An urgent need to improve access to care was the driving force behind the current National Stroke Strategy for England, which was launched in 2007 to address unacceptable variations in care which existed at the time. The strategy was to establish hyper-acute stroke units, closing smaller units, bringing resources and qualified staff together into larger centres. There has been real improvement, including a 46 per cent reduction in mortality. Notable success has been achieved in London and Manchester, where services have been reorganised.

However, stark variations in care persist and clinical audits continue to show failings in treatment. Up to 15 per cent of patients are still being denied vital treatment such as thrombolysis and 52 per cent wait more than the hour recommended in clinical guidelines for a brain scan to diagnose their stroke. Care for stroke survivors when they leave hospital can also be poor, with two-thirds not receiving a vital six-month review.

An example of this postcode lottery of care concerns a clot retrieval therapy known as thrombectomy. This is a mechanical treatment to restore blood flow to the brain, which can prevent some lasting damage. It has been deemed safe and effective by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, the health watchdog. Yet just 600 patients a year currently receive this therapy, meaning that more than 9,000 eligible patients are missing out, according to the most recent National Stroke Audit. The treatment requires trained specialists, support staff and equipment, all unavailable in many parts of the country.

The existing National Stroke Strategy for England comes to an end in 2017, with no current government plans to renew it beyond this year

In an effort to address this lottery of care, NHS England has announced ambitious plans to make thrombectomies available to 8,000 stroke patients a year over the next few years, via 24 neuroscience centres across the country. It is expected the treatment will start to be phased in later this year with an estimated 1,000 patients set to benefit across the first year of introduction. NHS England will work with Health Education England and trusts to build on the expertise that is currently available in these specialised centres, developing the workforce and systems.

There were also problems with the recruitment of consultants, with 40 per cent of stroke services having an unfilled stroke consultant post, up from 26 per cent in 2014. These shortages are likely to become more acute, particularly in the short-term, in line with recruitment difficulties experienced across the NHS.

Despite the achievements of the current National Stroke Strategy, the Department of Health says a new strategy is not needed because further improvements will be driven by the Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes Strategy (CVDOS) and the NHS Five-Year Forward View.

Campaigners, including the Stroke Association, argue this fails to recognise the distinct causes and impact of stroke, from communication problems to physical disability, which are not acknowledged by CVDOS or the Five-Year Forward View. What is needed, they say, is a national standard for stroke care.

Breakthroughs

Patient groups are concerned that momentum is stalling just as we enter a new era of stroke care, with breakthroughs in therapies such as thrombectomies and advanced technological devices to aid stroke rehabilitation. This new generation of high-tech tools offers the promise of a fuller recovery for patients who receive optimal hospital care in the immediate aftermath of a stroke. New methods of rehabilitation are being developed which are more engaging for patients and can often be done at home, reducing the need for hospital attendance.

Among the newest therapeutic tools are robotic exoskeletons, which attach directly to the affected part of the body to facilitate or enable movement. Robotic exoskeletons are well suited to therapy, since the support can be taken away gradually as patients improve. Exoskeletons may also relieve physical therapists of having to manually move the patients, so they can focus on the quality of the movements instead.

Another approach called tele-rehabilitation aims to increase the amount of therapy stroke patients get by making supervised rehabilitation available at home, integrating low-cost electronic video game plug-ins, such as a Nintendo Wii remote-controlled gun, with remote supervision by a therapist. Video game technology used in stroke therapy also includes virtual reality systems, with some that render scenes and objects in 3D. Some games with immersive environments may offer the greatest promise to stroke patients because they address cognitive problems along with sensory and motor problems.

Some of these therapeutic tools are at early stages of development and their effectiveness in encouraging rehabilitation is still being evaluated. Yet there is no question that technology offers great potential in aiding recovery.

The challenge is to ensure people affected receive urgent treatment in the immediate aftermath of a stroke to reduce the risk of irreparable brain damage and permanent disability. This will be aided by improving access to specialist care, which conforms to a national standard. It is also critical to improve public understanding of stroke, to help recognise the early signs and know what can be done to reduce the risk. A new national strategy for stroke would signal the government’s commitment to doing its best for stroke patients and their loved ones.

Present picture