More than 420 people in the UK will die today from cardiovascular disease (CVD), accounting for more than a quarter of deaths, according to the British Heart Foundation. CVD is caused by atherosclerosis, a build-up of fatty deposits that restricts blood flow, depriving critical organs of life-sustaining oxygen.

How do the statistical odds stack up against the estimated seven million people at risk? Although CVD is associated primarily in the public mind with heart attacks and strokes, it is also linked to diabetes, chronic kidney disease, peripheral arterial disease and dementia. Many people with one CVD condition go on to develop another.

Type-2 diabetes can aggravate atherosclerosis

For example, if you have type-2 diabetes, your chance of developing CVD is more than double that of the general population. High blood sugar levels in type-2 diabetes may exacerbate atherosclerosis.

Chris Askew, chief executive of Diabetes UK, says: “Diabetes is the fastest growing health crisis of our time.” The number of diagnoses in the UK has nearly doubled in the last 20 years from 1.9 million to 3.7 million. In addition, an estimated one million people have diabetes without knowing it.

A problem in either the heart or the kidney can have a sinister knock-on effect in the other organ, leading to failure of both

The American Heart Foundation estimates that worldwide more than two thirds (68 per cent) of people with type-2 diabetes aged 65 or over will die from some form of heart disease and 16 per cent from stroke.

Heart problems can have knock-on effect on kidneys, and vice versa

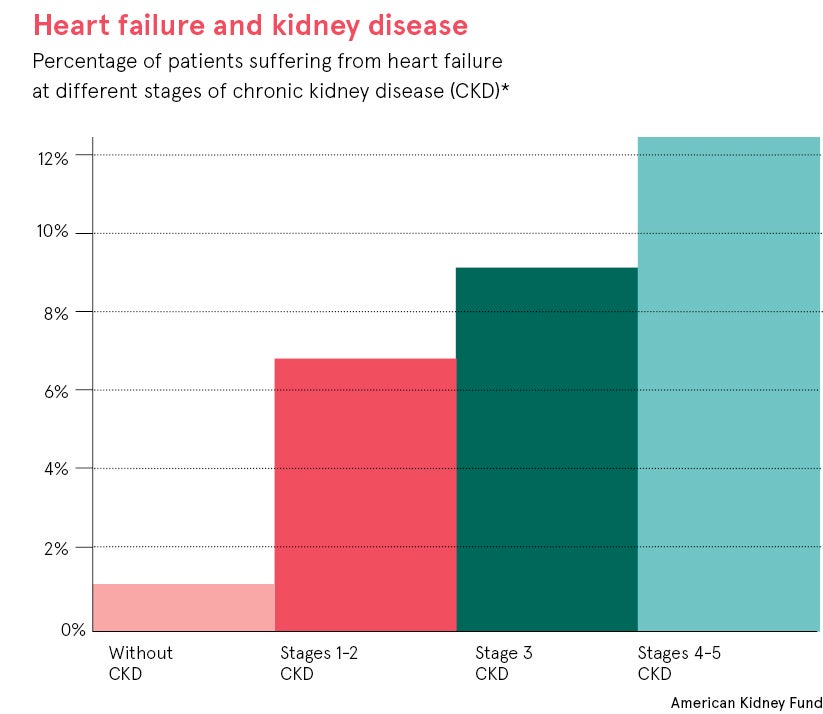

Similarly, a problem in either the heart or the kidney can have a sinister knock-on effect in the other organ, leading to failure of both. Chronic kidney disease is becoming increasingly common because of our ageing society and rising rates of diabetes.

Reporting in the British Heart Foundation online magazine Heart Matters, researcher Dr Maarten Koeners of the University of Bristol says: “In the UK, kidney disease affects 8.5 to 9 per cent of adults. One in three people will develop some level of the disease in their lifetime. It’s a condition that costs the NHS £1.45 billion a year and it kills more people than prostate cancer or breast cancer.

“There are no specific treatments, only treatments for the side effects such as high blood pressure, high blood glucose and anaemia.”

High blood pressure is a big focus of his work because both the kidney and the heart help to regulate blood pressure. “More than 65 per cent of patients with chronic kidney disease have high blood pressure,” he explains. “High blood pressure will accelerate loss of kidney function, increasing risk of heart disease.”

Blood pressure helps to regulate oxygen flow throughout the body, but it is especially important in kidney function. The kidneys make up just 1 per cent of body weight, but 10 per cent of oxygen usage, ten times more than would be expected, says Dr Koeners.

“The kidney is a hard-working organ. Kidneys filter all the circulating blood in your body many times a day [between 30 and 60 times] to produce a total filtrate of 180 litres,” he says. “Of these 180 litres, 99 per cent will be reabsorbed to produce a typical 1.8 litres of urine a day. All this activity makes it very susceptible to having less oxygen than it needs.”

A healthy lifestyle, from as young as possible, can prevent atherosclerosis

There are many different ways to treat CVD, but drugs and surgery alone will never be enough to reverse the so-called “Western way of death”. A healthy lifestyle is critical. Support from relatives can also help, while also encouraging entire families to lead healthier lives.

Lifestyle changes can produce dramatic results. For example, an estimated 60 per cent of cases of type-2 diabetes could be prevented or delayed by measures such as weight reduction, diet and regular exercise.

The younger people begin such regimes, the better. Post mortem examinations of 200 US soldiers, with an average age of 22, who died in the Korean War in the early-1950s revealed evidence of atherosclerosis in 77 per cent. A further study, in 1993, of men under 35 who died from non-cardiac trauma, such as accidents, showed signs of atherosclerosis in 78.3 per cent.

Restricting development of atherosclerosis in young and old alike would have major economic as well as health benefits. In its recent report, NICEImpact: CVD Prevention, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimated that, over a three-year period, treatment of high blood pressure could prevent 9,710 heart attacks and 14,500 strokes, saving the NHS up to £274.2 million.

Vital to recognise conditions like atherosclerosis as warning signs

The Department of Health advises that CVD should now be treated as a single family of diseases rather than as a number of separate entities. In its report, CVD Outcomes Strategy, the Department of Health says the traditional approach has led to disjointed, uncoordinated care.

Take the example of a patient, called Julia, who suffered from high blood pressure, heart failure and a heart rhythm abnormality. She then had a stroke. While in hospital she was also diagnosed with chronic kidney disease. Within just one year, she had more than 80 appointments with healthcare professionals. But she felt progressively unwell. A year later she was diagnosed with lung cancer.

According to the journal Heart BMJ: “If Julia had received integrated care with her at the centre, rather than care in silos by different teams, it is much more likely that her diagnosis of lung cancer would have been made earlier and might not have been fatal. Her experience of care would also have been better.”

Julia’s tragedy highlights that prevention is better than cure. This may sound trite, but it could prevent millions of premature CVD deaths and also reduce cancer risks.

Type-2 diabetes can aggravate atherosclerosis

Heart problems can have knock-on effect on kidneys, and vice versa