When Transport for London (TfL) introduced the Oyster card just over two decades ago, the move was hailed as a radical advance in ticketing. For instance, the smart card enabled 40 people to pass through one gate on the Tube every minute, compared with a mere 25 passengers using paper tickets.

The Oyster card served as the precursor to TfL’s next ticketing revolution: allowing payments using debit or credit cards and, more recently, app-enabled mobile devices. This so-called contactless system, developed in close collaboration with the banking sector, takes money directly from customers’ accounts when they tap the familiar yellow card readers. Introduced on London buses in 2012 and the Tube and several metro rail services in 2014, it has become the dominant method by which people pay as they go on the capital’s public transport network.

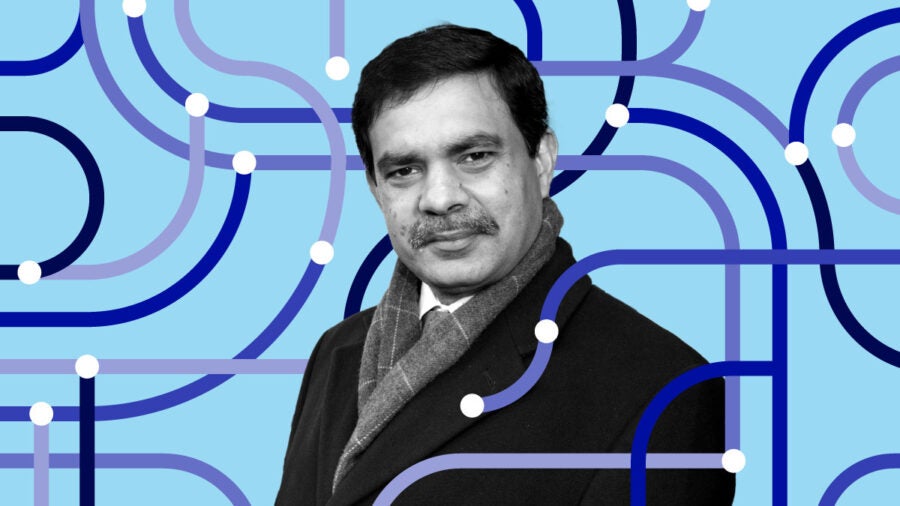

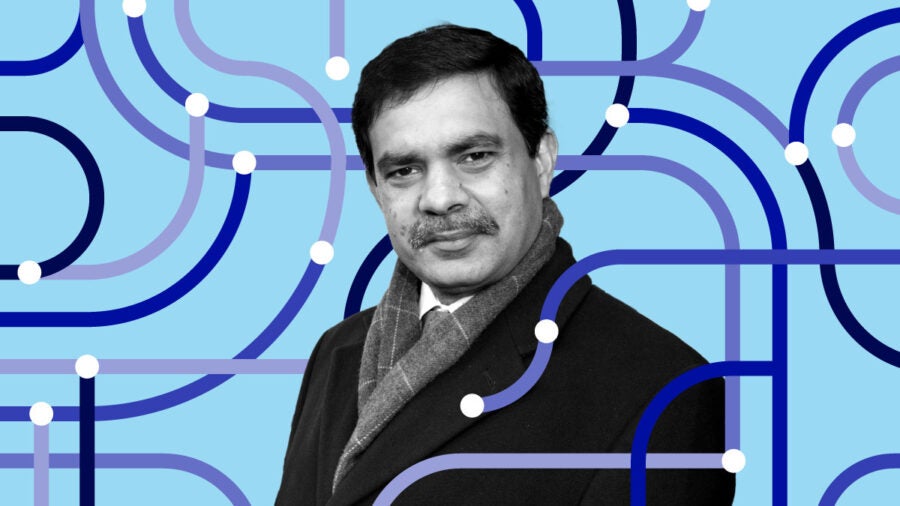

Shashi Verma, TfL’s chief technology officer, oversaw the implementation of the Oyster system and the development of contactless payments. Both advances highlight the operational gains that can be achieved when business strategy leads technology selection, he says.

Oyster has cut the annual cost of revenue collection by more than a third. A further cost saving of £50m a year to 2022 was delivered by the arrival of contactless payments, which enabled TfL to close almost all Tube ticket offices.

Identify business needs first, then find tech solutions

“Technology strategy must always be driven by whatever the business needs are. You can’t decouple the two – it’s dangerous to even try,” says Verma, who has held several roles at TfL since joining in 2002, including director of strategy and director of customer experience.

The Oyster card’s development was driven by a simple need to ease bottlenecks at station entrances and exits as passenger numbers increased. Contactless payment was the natural progression, creating new efficiencies and cost savings. It meant that passengers no longer needed to go to a ticket office or a machine to top up their Oyster credit.

“What we did was strip the business’s need down to its core. All we had to do was collect money, not run ticket offices,” Verma explains. “Ticketing is an unnecessary process.”

Innovation is not about technology; technology is the way innovation gets delivered

By choosing to build a contactless prototype system in house first, he took “a calculated risk”, explaining that this was a period when many comparable tech projects had limited success, with “everyone outsourcing everything”.

Convincing other people of the merits of going contactless wasn’t easy, as he recalls: “The idea didn’t have a huge amount of support in the organisation. For quite a long time, it had no buyers and I felt lonely. Often what you’re trying to do with technology is make it clear that the business can be run differently, which is what we did with contactless by closing ticket offices. But this went against deeply held beliefs that we needed to have that infrastructure, paper tickets and so on.”

Verma and his team eventually won their colleagues over when they delivered the prototype and people could see its potential.

“You need to be committed to it for a long period. That’s not something everyone’s willing to do,” he says.

Verma stresses that, to gain the level of credibility you require in an enterprise to make a radical change, you need to be running the day-to-day operations as efficiently as possible.

“To even have that discussion with the rest of the organisation, you must fulfil everything they require of you to such a high quality. Only then can you discuss the transformational things,” he says.

Breaking down the silos for organisational transformation

In 2017, Verma set up a technology and data department. It was something he’d been trying to convince TfL to do for some time, but the breakthrough came after the corporation started coming under severe financial pressure.

Until that point, the delivery of technology and data was fragmented, much like at many other organisations, he says. There were several teams responsible for various technological aspects. Verma saw an advantage in combining their strengths – for instance, the intense customer focus of customer-facing teams and the agility of digital teams – and spreading those across one department.

“My core argument was that, before you learn from any other organisation, there’s much that can be achieved by learning internally,” he says. “But this is not something you can do just by putting people in a room; it must be forced. If you try doing it by diffusion, it will take a very long time.”

All we had to do was collect money, not run ticket offices. Ticketing is an unnecessary process

The desired culture change happened quickly. Within six months of assembling his department, “the whole place was turned upside down”, he recalls.

The reorganisation also led to financial benefits. The smashing of silos reduced the cost of technology delivery by a third through improved teamwork and efficiency, according to Verma. It also boosted morale and, further down the line, solved a staff retention problem too.

“The organisational change forced everything out into the open. Many people left because they found the light being shone on them very uncomfortable,” says Verma, but he adds that this ensured that the right people were eventually placed in the right positions.

Productivity comes from looking at the long term

What does Verma consider to be the key to success with tech transformations, especially in times of economic uncertainty?

“While you always have to be responsive to short-term requirements, you must also have your own long-term goals and drive towards them,” he says. “Otherwise, you’re just being reactive; where’s the productivity coming from? Productivity comes only from looking at the long term and understanding your business, its dynamics and economics.”

Verma adds: “Remember that innovation is not about technology; technology is the way innovation gets delivered.”

But it’s hard to innovate on an unstable base. TfL has been under extreme pressure to cut costs since 2015, after the government slashed its planned cessation of grant funding by two years. As a result, it lost out on £2.8bn between that year and 2021. If that weren’t bad enough, most of its revenue from ticket sales and advertising dried up during the Covid lockdowns and hasn’t yet fully recovered.

At present, TfL is locked into six-monthly funding negotiations with the government. This is putting its successful delivery model at risk, according to Verma.

“Now, so much of our effort goes into budgeting, rather than productive work, and cost-cutting, which we used to do in a strategic way,” he laments. “If we’d created a startup to develop our contactless system, that business would be valued at tens of billions of pounds now. But it’s an open technology, delivered through public sector innovation, that’s providing huge public benefit.”

When Transport for London (TfL) introduced the Oyster card just over two decades ago, the move was hailed as a radical advance in ticketing. For instance, the smart card enabled 40 people to pass through one gate on the Tube every minute, compared with a mere 25 passengers using paper tickets.

The Oyster card served as the precursor to TfL’s next ticketing revolution: allowing payments using debit or credit cards and, more recently, app-enabled mobile devices. This so-called contactless system, developed in close collaboration with the banking sector, takes money directly from customers’ accounts when they tap the familiar yellow card readers. Introduced on London buses in 2012 and the Tube and several metro rail services in 2014, it has become the dominant method by which people pay as they go on the capital’s public transport network.

Shashi Verma, TfL’s chief technology officer, oversaw the implementation of the Oyster system and the development of contactless payments. Both advances highlight the operational gains that can be achieved when business strategy leads technology selection, he says.