Le Bourget, aka the Paris Air Show, is the biennial aerospace show-and-tell where manufacturers reveal snazzy new aircraft prototypes, jets zoom overhead with gravity-defying manoeuvres and, most importantly, monumental airliner orders are signed off.

This June’s show, attended by 322,000 visitors, delivered the anticipated mix of aeronautical showmanship, aerobatic pyrotechnics and telephone-number deals, with $150-billion-worth of orders announced for 934 commercial aircraft.

But beyond all that there was another dimension, something that transcends commerce and technology. It’s to do with national aspirations, for there were two conspicuous blips on Le Bourget’s radar – Russia and China. 2017 is the year in which these two countries individually and collaboratively assert a new stance in the aerospace arena as they kick-start their transition from consumers to contenders.

China has been an avid customer of Western-built airliners for decades. At Paris, Xiamen Airlines, a regional subsidiary of China Southern Airlines, signed a memorandum of understanding for ten Boeing 737 MAX 10 airliners, valued at $1.2 billion. These will top up Xiamen’s all-Boeing fleet comprising nine 787 Dreamliners, 149 Next-Generation 737s and four 757s. The carrier plans to grow its fleet to 280 airliners by 2020; impressive statistics for a domestic airline, dwarfing the fleet numbers of most national carriers.

Airbus is also a beneficiary of China’s predilection for Western planes with the announcement earlier this month that China Aviation Supplies Holding Company (CAS) had contracted to purchase 140 aircraft from the Toulouse-headquartered manufacturer. That’s in addition to the 1,440 Airbuses currently in service with various Chinese airlines.

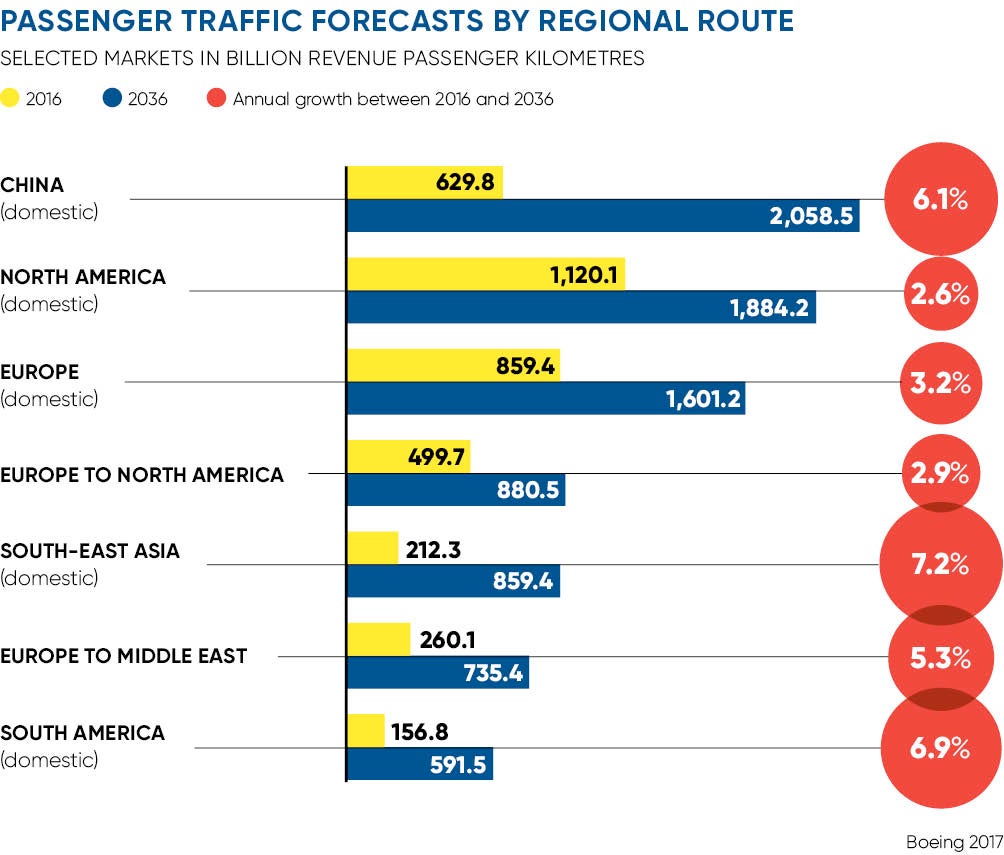

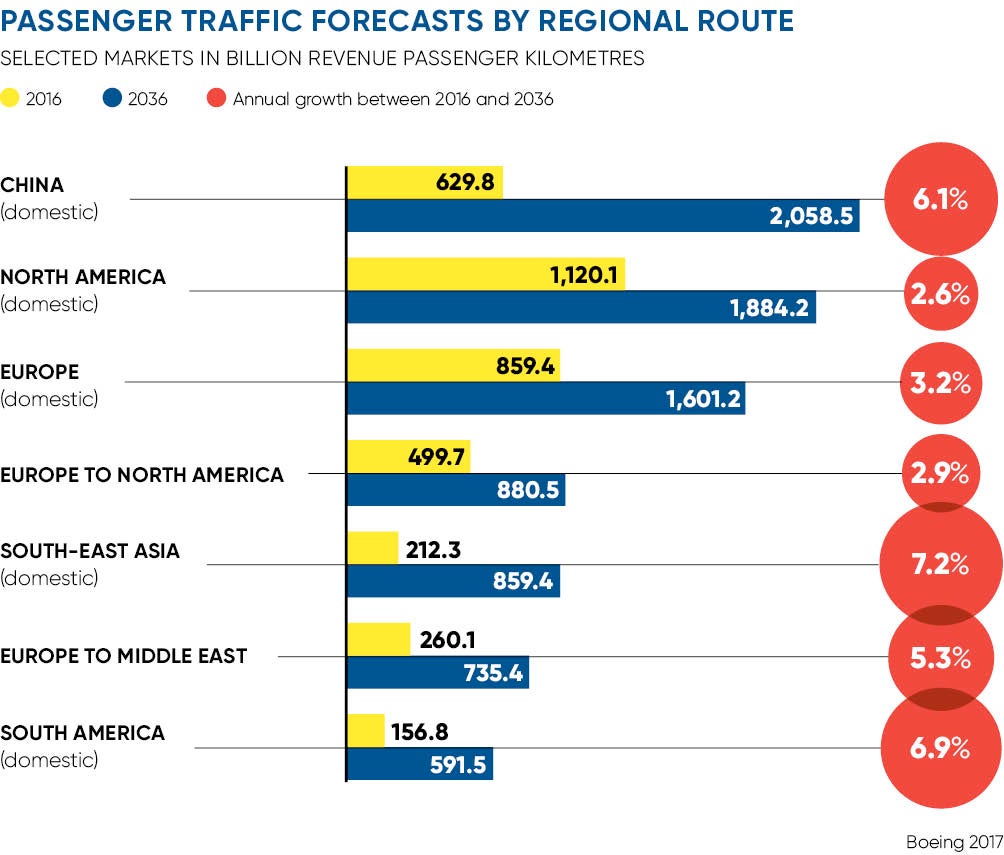

The Xiamen and CAS orders are emblematic of the scale of growth in Chinese regional aviation which is expected to quadruple over the next 20 years. Boeing calculates that by 2036 China will be the largest domestic airline market in the world. And to put the significance of this into context, in its 2017-2036 Global Forecast, Boeing identifies that over the next 20 years there will be a global market requirement for 41,030 new aircraft, worth $6.1 trillion.

This slices up into 7,530 planes in Europe, 8,640 in North America, 3,350 in the Middle East, 3,010 in Latin America, but the lion’s share will be headed to the Asia-Pacific region where 16,050 will be delivered. That’s a lot of business in China’s backyard, which brings us to those radar blips as Le Bourget signalled what could be a disruption of the equilibrium of global civil airliner manufacturing held by Airbus and Boeing.

The alliance

Challenging Boeing’s 737 MAX 10 and its European rival the Airbus A321neo, the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) stand at Le Bourget promoted its C919 airliner, while Russia’s United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) plugged its MC-21 medium-haul jet. These Chinese and Russian contenders made their maiden flights on May 5 and 28 respectively this year; both offer similar configurations to their American and European counterparts.

In their domestic markets, order books are filling up as 285 MC-21s have been ordered, 50 slated for Aeroflot with deliveries starting in 2019, and COMAC has already sold 600 C919s to 24 airlines in China.

2017 is the year in which these two countries individually and collaboratively assert a new stance in the aerospace arena

But even more intriguing on the COMAC stand was a model of a Sino-Russian long-range wide-body aircraft sporting a three-class cabin layout with 280 passenger seats. The plane’s 12,000km range aligns with the market segment presently served by Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner and Airbus’s A350.

Underpinning this Sino-Russian collaboration is a COMAC-UAC partnership, endorsed by Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin who signed a joint venture as part of a “major strategic co-operation programme against the background of further developing the comprehensive strategic partnership between China and Russia”. The joint entity is known as the China-Russia Commercial Aircraft International Corporation (CRAIC), based in Shanghai.

Unsurprisingly, elements of the media have been rubbing their hands together, quickly characterising this emerging story as a classic East-West showdown, threatening the status quo of civil aerospace. But the reality is more nuanced, for in the short and medium term the MC-21 and C919 rely on key Western components:

Russia’s airliner is powered by US-built Pratt & Whitney PW1000G-JM engines; likewise, COMAC’s jet has CFM International LEAP-1C engines beneath its wings. CFM International is a joint venture between America’s General Electric and France’s Safran Aircraft Engines.

Of course, Western engines could in the future become merely optional if indigenous ones become available: Russia’s United Engine Corporation (UEC) displayed its PD-14 engine at Le Bourget, designed specifically for the MC-21 and presently in its testing phases.

“We are going to base our further work not only on exporting the end products, but firstly on taking part in the export-oriented projects; in other words, co-operation with foreign companies in the field of developing engines and components,” says Alexander Artyukhov, UEC’s director general.

And that mirrors CRAIC’s objectives. It recently announced that it’s on a quest to procure international partners to ensure that what is brought to market is compliant with global industry norms.

“We will follow the latest international mainstream airworthiness standards and build more competitive long-range wide-body aircraft,” says Jin Zhuanglong, chairman of COMAC, while his Russian counterpart Yury Slyusar, president of UAC, says the wide-body programme “is testimony to China and Russia’s determination to engage in long-term co-operation”.

CRAIC says it will carry out global bidding based on market-oriented and standardised principles, and provide priority to suppliers that are more experienced, can provide competitive product and are willing to share the risk during development through local investment or joint ventures.

Becoming technologically self-sufficient might be a long-term objective, but for now Russia and China appear intent on collaborating beyond borders with partners that have the competence to raise the quality and competitiveness of their airliners. And that has to mean greater choice for passengers worldwide.