The UK has been at the cutting edge of artificial intelligence (AI) innovation, from Alan Turing, the pioneering mathematician and computer visionary, who launched the field, to DeepMind’s AlphaGo, the first computer program to defeat a professional Go player in 2015.

Several pioneering AI companies were founded in the UK, including DeepMind, SwiftKey and Magic Pony, all of which were acquired by US companies – Google, Microsoft and Twitter – for $500 million, $250 million and $150 million, respectively. Over the last few years, the UK government has launched its Office for AI and Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation. But is the UK still an AI leader?

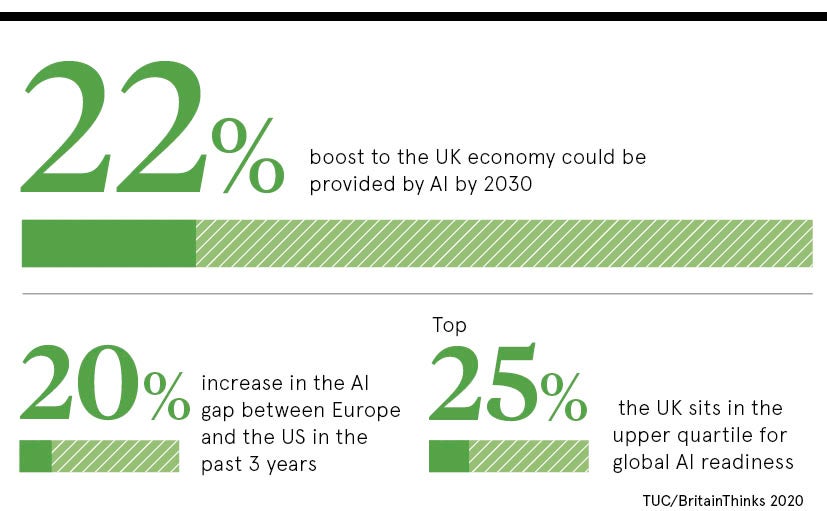

In 2019, McKinsey Global Institute placed the UK in the top quartile for “AI readiness”. How is the UK maintaining this position in a competitive landscape, both in a business sense and a governmental one?

No country can hold a candle to the United States and China when it comes to AI, but the UK is one of Europe’s leaders, according to the McKinsey report. The UK is globally in the top quartile for research, startup investment, digital absorption, innovation foundation and ICT connectedness. It does, however, rank lower on automation potential and human capital.

Bringing AI skills from the top to a wider population

The UK has many leading researchers, who are published in the top academic journals. Christine Foster, chief commercial officer at The Alan Turing Institute, says: “The UK has eminent researchers, such as Christina Pagel, who works on mathematical tools to support delivery of health services; Mark Girolami, who is developing and applying advanced statistical and computational techniques to engineering challenges; Maxine Mackintosh, who has founded One HealthTech,” which supports under-represented groups in health tech innovation. There are many others.

Lee Harland, founder and chief scientific officer at SciBite, an Elsevier company, says: “We’re very good at the basic science; a strength of the UK has always been our intellectual output. The Cambridge-Oxford-London triangle is a hub for talent. Because AI is a broad skill that can fit just as much into gaming as it does into healthcare, within the triangle there is a lot of opportunity for people to move around, even into different industries, without trekking halfway across the world.”

The question is whether this skillset filters down to a broader population. “Recruiting talent from outside the UK will always be important, but we need to bring the AI skills closer to our schools and universities,” says Harland.

“You don’t need a degree in mechanical engineering to drive a car and you don’t need a degree in statistics to use machine-learning. There are some great initiatives for data science and AI-centric courses appearing in our universities; this needs to be accelerated and cascaded down, at least conceptually, to school age.” Like most countries, the UK faces a shortage of people with advanced technological skills. Wider education could remedy that.

Turning innovation into scalable business opportunities

Foster adds: “In the UK, we are fluidly connecting and convening across the public sector, private sector and third sector. Look at the AI Council [an independent expert committee that advises the government]; it’s a great example of what can happen when people from industry, public sector and academia come together, sharing their broad range of background and expertise to the AI ecosystem.”

Despite slightly higher investment in AI, the UK lags behind France, Germany, Japan and South Korea when it comes to AI patents, according to McKinsey. What’s more, an independent review commissioned by the government noted that “universities should promote standardisation in transfer of intellectual property”. This would make it easier to create spin-out businesses.

Taking an idea and turning it into a business takes a combination of factors, says Harland. “There are a lot of institutions out there to advise – Innovate UK, Digital Catapult – but it’s often very obtuse in terms of what they can do and how they help.” He says other European countries are better at being explicit about which agencies do what for startups. “I think it’s very hard to understand that in the UK landscape,” says Harland.

A long-term strategy for Britain to be an AI leader

There is something of a “space race” in the AI realm, says Dr Michael Feindt, strategic adviser of Blue Yonder. America is investing fifty times more in AI than the UK, and China is investing eight times more. “We are increasingly seeing promising UK startups being acquired by large US companies before they can mature, limiting the UK’s ability to make up ground on other countries,” says Feindt.

Historically, many innovations in the computer industry have been pioneered by women. The first computer programmer was Lady Ada Lovelace, while actress Hedy Lamarr invented the technology that enabled wifi, GPS and Bluetooth. In the mid-80s, almost 40 per cent of US computer graduates were women. But the AI industry now faces what Bill Gates called the “sea of dudes problem”. A greater diversity of people and data would counteract some of the bias that algorithms have ingested so far.

To stay at the forefront of AI, the UK needs a long-term strategy spanning ten to fifteen years, rather than just one or three, argues Foster at The Alan Turing Institute. This strategy needs to ensure data is more accessible to AI companies, that innovative pilots can be scaled and ethical frameworks applied.

“We have a long history in AI. Our researchers know they’re standing on the shoulders of giants and that we have the ability to move the whole field forward,” she concludes.

The UK has been at the cutting edge of artificial intelligence (AI) innovation, from Alan Turing, the pioneering mathematician and computer visionary, who launched the field, to DeepMind’s AlphaGo, the first computer program to defeat a professional Go player in 2015.

Several pioneering AI companies were founded in the UK, including DeepMind, SwiftKey and Magic Pony, all of which were acquired by US companies – Google, Microsoft and Twitter – for $500 million, $250 million and $150 million, respectively. Over the last few years, the UK government has launched its Office for AI and Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation. But is the UK still an AI leader?

In 2019, McKinsey Global Institute placed the UK in the top quartile for “AI readiness”. How is the UK maintaining this position in a competitive landscape, both in a business sense and a governmental one?