Slaughter at a Friday night concert in Paris, running down pedestrians on a promenade in Nice, and stabbing diners in London bars and restaurants. The brand of terrorism, which has brought carnage to European cities, has also exposed weaknesses in protecting vulnerable soft targets such as tourist sites and shopping districts.

The challenge for any democracy is how to respond to threats while upholding a social order, which groups like Islamic State (Isis) seek to annihilate. In the 1970s and 1980s, Spain’s ETA and terrorist groups fighting in Northern Ireland initially concentrated their violence against government figures. Al Qaeda and Isis have instead directed their campaigns at civilians.

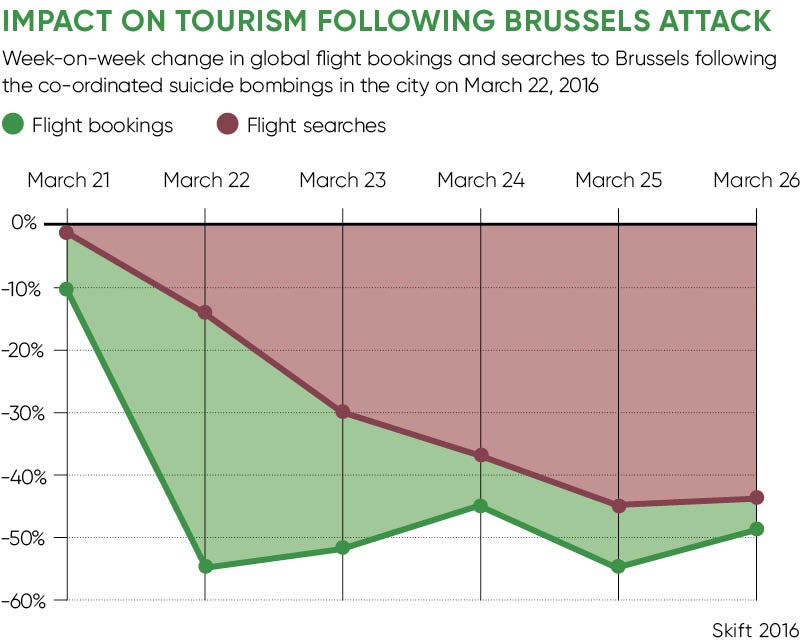

Suicide bombings, knife attacks and shootings not only cause a significant loss of life, but also have an ancillary effect on tourist attractions, hotels, restaurants and shops.

After the bloodshed at the Bataclan, the most famous attractions in Paris recorded double-digit declines as tourists, who were alarmed at the likelihood of further attacks, stayed away. According to the city’s tourist board, attendance at the Grand Palais fell by 43.9 per cent and the number of tourists visiting the Arc de Triomphe dropped by 34.8 per cent. Throughout 2016, France saw an estimated €750-million drop in tourism revenue.

Central Paris went into lockdown following the terrorist attacks in November 2015; French luxury goods businesses such as Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton suff ered from weak sales in the following quarter

As France has seen the militarisation of its city streets and the introduction of bag searches at shopping malls and cinemas, entertainment and retail sales have suffered. The French luxury goods businesses, valued at $18 billion, saw weak revenue during the first quarter of 2016. Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton last summer recorded a slowdown in its year-on-year sales growth of 3 per cent. In 2015, Prada’s year-on-year profits fell by 27 per cent amid a slowdown in tourism-driven sales. In its annual report, the company cited terrorist attacks in France as a factor.

Larger firms view terrorism as the cause of uncertainty in global financial markets, while smaller businesses depend on local communities and tourists

For businesses operating in countries including the UK, France and Germany, terrorism poses a new threat to staff and assets in a number of ways. Larger firms view terrorism as the cause of uncertainty in global financial markets, while smaller businesses such as cafés depend on local communities and tourists. Providing a risk-free environment for staff in a restaurant in London is different to safeguarding energy workers in Baghdad or Riyadh.

“In Europe, the terrorist threat is very specific and widespread,” says Riccardo Dugulin, a senior analyst at Drum Cussac, which provides security insight and solutions to businesses. “A terror event can happen at any time and there is no mitigation risk you can take. In countries like Libya and Iraq, you can have a hands-on approach because of the environment. That is harder to do in Europe.”

Faced with an increase in the number of terrorist incidents targeting businesses and supply chains, security has become a priority for the European Commission (EC). In 2014, the EC launched a number of research projects under an €80-billion innovation scheme called Horizon 2020. The programme, which is funded until 2020, has a number of initiatives which focus on eliminating terrorist threats to businesses and the infrastructure they rely upon.

While the most obvious consequence of terrorism is the loss of life and the physical destruction of traditional bricks-and-mortar buildings, attacks also pose risks to online stores, the supply of cargo, and gas, water and electricity supplies.

Horizon 2020 projects include CASSANDRA (Common Assessment and Analysis of Risk in Global Supply Chains), which protects the global transport of shipping containers. Another initiative, FLY BAG2, has developed a technology which can be used to help airplane cargo holds and cabins survive a Lockerbie-sized explosion. A project called ACT4INFRA aims to develop a system to defend water and gas utilities from terrorist or criminal attacks.

According to an EC spokesperson: “Recent attacks in the UK, Germany and Spain reiterated the need to better protect public spaces. The Commission has stepped up its work with national authorities, practitioners and relevant business operators in this respect. Dedicated working groups are envisaged to start work in September on protection of soft targets.”

For business owners, protecting staff and retail buildings alone isn’t enough. The last few years have also seen an increase in online attacks as well as the theft of cargo and trucks by organised crime. The Transport Asset Protection Association (TAPA) says 2016 saw 2,611 recorded incidents of cargo crime in the Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) region, the highest level in the association’s 20-year history and a 72.3 per cent rise year on year. The loss to businesses for these thefts exceeded €77 million.

“The devastating use of trucks in terror attacks in France, Germany and the UK in the past 14 months has demonstrated not only a shift in terrorists’ mode of operating, but also the vulnerability of trucks and, of course, their drivers,” says Thorsten Neumann, chair of TAPA EMEA. “It is now of paramount importance to all stakeholders that we take every sensible and proactive precaution to protect vehicles to stop them falling into the hands of people who want to use them as a weapon to harm others.”

Businesses that outsource digital services, such as online stores and loyalty programmes, will also have to address an increase in the number of cyber attacks. “Businesses have traditionally outsourced their technology needs to keep costs low,” says Stefano Mele, a partner at Moire Consulting Group, an Italian security and insights firm which advises companies in Europe. “That may change depending on the threat level to the service required.”

James McAlister, director of Crisis Prepared and chair of the Business Continuity Institute, which advises firms on issues of resilience, adds: “It is natural for business owners to worry about terrorism after a big attack. Our advice to businesses is always to try and gauge the threat level posed to them. Why do they think they might be attacked? How best can they protect themselves? Staff are a priority, so we try to look at areas where they might be vulnerable.”