In the heady days of 2009, Professor David Nutt of Imperial College London, then the government’s chief drug adviser, claimed that certain illegal drugs, including LSD, were less harmful than alcohol and tobacco. An expert in neuropsychopharmacology, he was citing scientific evidence, but the stigma that had shrouded psychedelic drugs since the 1960s cast a long shadow. Nutt’s stance caused political and public uproar; he was promptly sacked.

Fast forward to today and Imperial College London has its own Centre of Psychedelic Research, where Nutt is Deputy Head. It has a prolific research output and enviable global reputation when it comes to studying psychedelic experiences. Research many believe will offer revolutionary new treatment avenues for a range of mental health disorders. If these therapeutic medicines can get past the necessary regulatory and legal hurdles, that is.

Understanding the science of psychedelic experiences

LSD was first synthesised in a pharmaceutical laboratory in 1938 (Sandoz in Switzerland, which is now Novartis), but its popularity as a recreational drug in the 1960s invoked a moral panic that led both the UK and US governments to make it illegal, which stymied scientific research on psychedelic drugs for the rest of the century.

The scientific community’s reputation had not been helped by the fact Timothy Leary, while a clinical psychologist at Harvard, had encouraged his students to take psilocybin, the psychedelic compound found in magic mushrooms, and allowed them access to the department’s supplies.

The psychedelic research hiatus ended in the early 2000s when Roland Griffiths, a Professor in Psychiatry and Neurosciences at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in the USA, who had become interested in “altered states of consciousness” through his own experience of meditation managed to convince the US government and Johns Hopkins to let him use healthy volunteers to study psilocybin.

Griffiths was curious but had no expectation of what his research might show, yet the results were fascinating, with 70 per cent of the volunteers saying they’d had one of the five most meaningful experiences of their lives while on the drug, comparable to the birth of a child or death of a parent. His findings were published in 2006 in the journal Psychopharmacology, and they kickstarted a new dawn in psychedelic drug research.

How psilocybin-assisted therapy can help with mental health

“Understanding consciousness is the major frontier of our age,” says Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, head of the Centre of Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, and a protégé of Professor David Nutt. “[The 2006 Griffiths study] helped to contextualise why psychedelics were interesting. They induce these big experiences that can change your life.”

While this is interesting to scientists from an existential point of view, it’s the potential benefits these psychedelic drugs can bring to people with mental health disorders that is especially significant. Johns Hopkins, which now also has a specialised centre for psychedelic and consciousness research, has demonstrated the therapeutic effects of psychedelic drugs in people suffering from addiction, including smoking and alcohol, existential distress caused by life-threatening disease, and treatment-resistant depression.

At Imperial College, Carhart-Harris has made similarly striking discoveries including studies which have shown psilocybin to be an effective treatment for eating disorders, suicide ideation and severe depression. In one study, which will be published next year, psilocybin performs far better than a conventional antidepressant drug.

Normally, pharmaceutical drugs target a particular disease state or symptoms, so why are these single interventions potentially effective for so many different disorders? “Psilocybin increases plasticity in the brain, its ability to change,” says Carhart-Harris. The drug provides a pivotal mental state he describes as “a fork in the road”.

He says: “With depression and anxiety, people have developed these maladaptive ways of thinking and behaving, or in addiction, behaviour is channelled towards whatever the object of addiction is. What psychedelics do is they go in and target that core, the fact you’ve fallen into a certain way of being, and they increase your ability to change it.”

And what researchers have found is that these changes in thinking stick long after treatment. “Patients rewrite their own life narrative; they change the course of their lives going forwards,” says Griffiths.

“Psychedelics target the fact you’ve fallen into a certain way of being, and they increase your ability to change it.”

Psychedelic drugs have been shown to have a low risk of toxicity (another concern from the 1960s). They appear to offer a new kind of experience-based medicine, unlike conventional antidepressants, which only affect you while you’re taking them, and work by muting rather than fixing symptoms.

“Psychedelics are very disruptive scientifically to our assumptions about paradigms in mental health,” says Carhart-Harris. Though he also cautions: “They’re not party drugs, they’re incredibly powerful and should be treated with respect.” Research treatments are always done in the presence of trained therapists and volunteers are well screened in advance as psychedelic assisted therapy is not suitable for everyone.

Investment growth in psychedelic drug research

Almost all of the pioneering research into psychedelic experiences done over the last 20 years at both Imperial College and Johns Hopkins has been funded by private foundations or individuals. As Griffiths says: “Without philanthropic support, the re-emergence of psychedelic research and treatment would not have occurred.”

JR Rahn is the founder of MindMed, a New York-based startup, which is developing psychedelic drugs to treat mental illness and addiction. “Translating this science into scalable medicines,” he says.

MindMed are already listed on Canada’s NEO exchange with a market cap of 463.15M (as of November 2020) and aim to be the second psychedelic company to be listed on Nasdaq (the first was UK-based Compass Pathways). Rahn believes people want to invest in a company like MindMed to impact a positive change in society, a mindset that has accelerated during Covid 19.

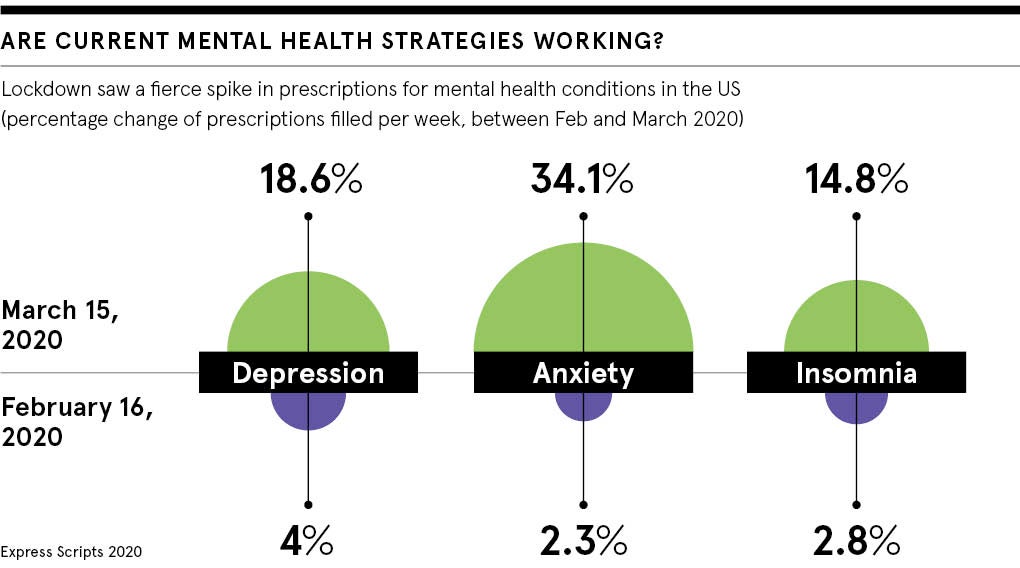

“Every family in America has a story to tell,” he says. “40% of US citizens had some form of mental health incident or substance abuse disorder in the midst of Covid 19; 40 per cent of investors might have the same variation.”

Moving beyond the war on psychedelic drugs

On November 3rd 2020, along with voting Trump out of office, citizens in the state of Oregon voted to decriminalise psychedelic drugs for therapeutic use. Rahn tells me he thinks the vote is a step in the right direction, and evidence of how many people are looking for help with mental health disorders and addiction right now. But he believes the more sensible path to getting medicines approved is through the FDA at a national, as opposed to state, level.

“We want to pursue everything in a federally compliant manner,” he says. “The cannabis industry didn’t provide the data or do the research [to ensure their products were] federally compliant substances and I don’t want to make the same mistakes.”

Rahn feels getting the drugs approved would help reassure those with a more conservative mindset when it comes to psychedelics. “You show them the drug approvals… that vote of confidence as an industry.”

What would Carhart-Harris say to the UK government about the potential upside of licensing psychedelic drugs for therapeutic use? “I’d say they don’t want to fall too far behind in this legitimate and exciting domain of mental healthcare. I do believe fortune will favour the brave here, in a way that medicinal cannabis has benefited the Canadian economy.”

He already fears that demand could outstrip supply (they get a huge number of applicants for scientific research), and also points to the number of mental health professionals that would need to be trained up, as each treatment session needs a qualified therapist to be present.

It would be a big boost to the psychotherapy industry, and to pharmaceutical manufacturing businesses in the UK, as a lot of the psychedelics including psilocybin are synthesised here.

“Economically there are good reasons for the government to be thinking about psychedelics,” he says, alongside the humane incentives, which would in turn also bring huge cost savings to overstretched mental health services in the NHS. Politicians just need to stop having 1960s flashbacks.

Psychedelics point to flaws in gold standard of medical research

The double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial has long been considered the gold standard for analysing medical research, for its ability to produce knowledge without bias. But Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, head of the Centre of Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, believes that work with psychedelics suggests faults in the methodology. “Psychedelics are really interesting because they even challenge the paradigms by which we assess medical intervention, as the randomised, double-blind trial is flawed when you test psychedelics, as participants know.” This being largely because it is fairly obvious to participants whether they have taken a placebo or a synthetic equivalent to magic mushrooms…

“But what they also do is remind people that maybe the randomised, double-blind trial isn’t so rigorous after all, because even if you look at the data with antidepressants, the methodology isn’t very effective. I think the guess rates are around 90%.” With participants noticing side effects, such as having a dry mouth, which alert them to the fact that they’ve been given the antidepressant rather than a placebo.

“It’s this performance that’s been done in science, but I think the paradigm is flawed. In the future the most useful work will be done using a different approach to assess the benefits [of a drug], taking into account individual differences.”

Carhart-Harris believes research will become more pragmatic, using real-world data and data registries. “Big data will very much complement controlled research and whatever double-blind randomised control trials are done. It will tell us so much more, alongside more naturalistic sampling of the use of psychedelics.”

That said, Carhart-Harris is pleased to have performed successful randomised double-blind trials for now, including a forthcoming study which compares psilocybin-assisted therapy to an antidepressant for treating depression, given the regard in which the gold standard trials are held. “I’m glad we’ve played the game,” he says.

In the heady days of 2009, Professor David Nutt of Imperial College London, then the government’s chief drug adviser, claimed that certain illegal drugs, including LSD, were less harmful than alcohol and tobacco. An expert in neuropsychopharmacology, he was citing scientific evidence, but the stigma that had shrouded psychedelic drugs since the 1960s cast a long shadow. Nutt’s stance caused political and public uproar; he was promptly sacked.

Fast forward to today and Imperial College London has its own Centre of Psychedelic Research, where Nutt is Deputy Head. It has a prolific research output and enviable global reputation when it comes to studying psychedelic experiences. Research many believe will offer revolutionary new treatment avenues for a range of mental health disorders. If these therapeutic medicines can get past the necessary regulatory and legal hurdles, that is.