Returning American manufacturing jobs to US soil was a headline cause for the Trump presidential campaign. Now, as then, President Trump rails against the culprits he sees as standing in the way of “American jobs for American people” – large trade deals, global outsourcing, competition from China and immigration. But rarely, if ever, does he touch upon automation.

“Automation was the secret Rosetta Stone of this election,” says Mark Muro, senior fellow and policy director of the metropolitan policy program at the Brookings Institute. “It didn’t determine the outcome, but the economy is the overwhelming backdrop to what happened.”

Researchers at the Oxford Martin School, in corroboration, have found evidence of a relationship between electoral districts’ exposure to automation and their share of voters supporting Donald Trump, strongly suggesting, as they put it, that “the presidential election was a riot against the machines by democratic means”.

The rise of automation

The past 200 years have seen increasing automation, vastly improved global living standards, but “creative destruction” – famously described by economist Joseph Schumpeter as accompanying technological change – brings with it winners and losers. Since the computing age began in the early-1980s, growth has failed to trickle down to ordinary Americans. From 1979 to 2013, productivity growth was eight times faster than growth in workers’ hourly compensation. As productivity grew by 64.9 per cent, hourly compensation grew by only 8.2 per cent for 80 per cent of the American workforce, while the top 1 per cent of earners saw cumulative gains in annual wages of 153.6 per cent.

A vote for Trump may have represented a vote for change, but it is far from clear whether the Trump administration fully apprehends the drivers of voters’ grievances and the actions required to mitigate them or whether it is expediently ignoring them.

Automation is already causing political polarisation and swings to the left and right

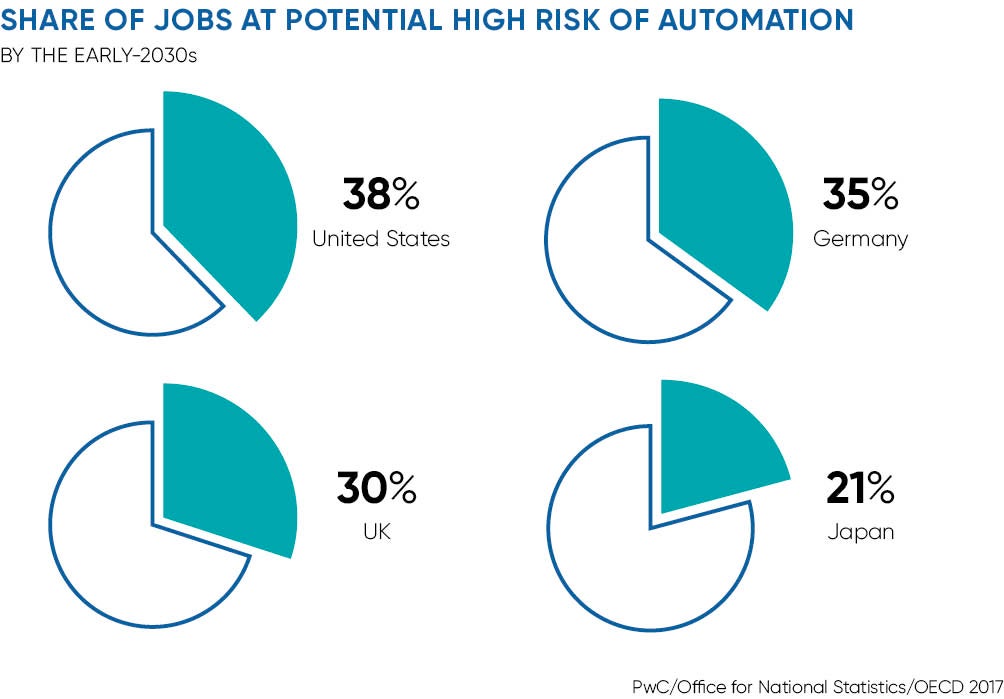

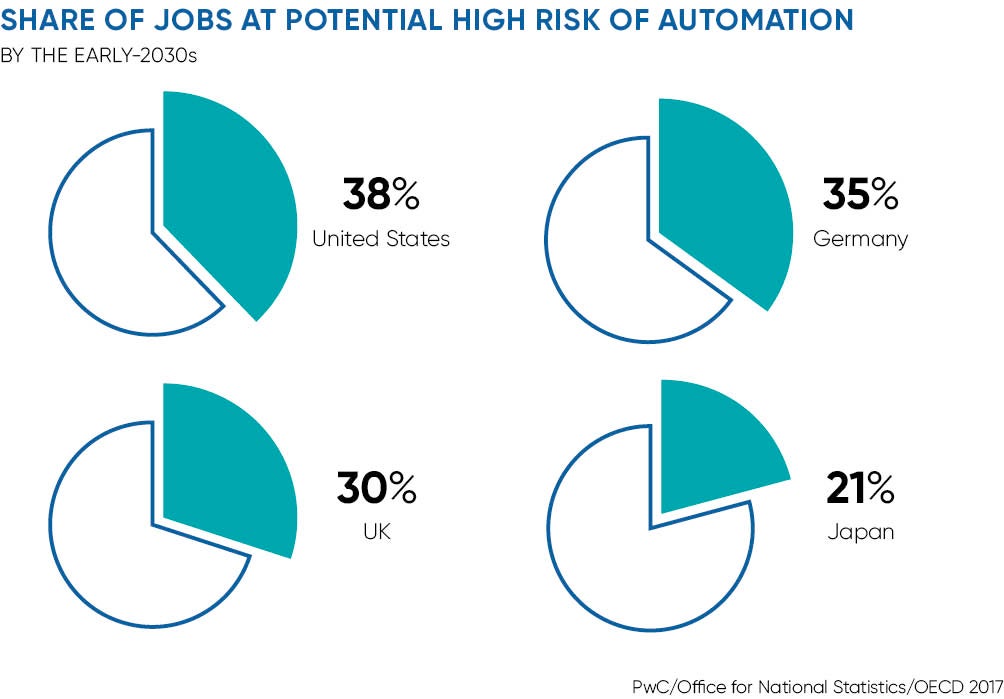

David Autor, economist at MIT, believes automation is already responsible for greater manufacturing job losses than outsourcing or trade. Yet meanwhile, Trump’s treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin has declared automation “not even on our radar screen” and that the problem is likely to be “50 to 100 more years away”.

For the time being, some job losses to automation will be held off by upfront costs that are at present too prohibitively large for most large and medium-sized companies. But over the next decade, Boston Consulting Group predicts, the price of industrial robots and their enabling software will drop by 20 per cent, while their performance will improve by 5 per cent each year. Given the private sector’s openness about automation and the public’s palpable anxiety, why is the Trump administration not giving the issue the attention it requires?

Thomas Davenport, author of Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines, argues in the Harvard Business Review, that Trump, in his business-style and as supposed author of The Art of the Deal, “clearly has a penchant for sparring with opponents in highly visible negotiations… but automation-related job loss is more difficult to negotiate”. Mr Davenport surmises: “It’s a complex subject that doesn’t lend itself to TV sound bites or tweets.”

Productivity levels

President Trump may be able to get away with trade protectionism, but protectionism against productivity is not an option. Ever since the British jumpstarted the Industrial Revolution by doing what no other nation had before dared, sacrificing their citizens’ employment to productivity, the marriage between politicians in Western economies and productivity has been sealed. Productivity is the ultimate goal of automation and an important factor in long-term economic growth, a measure by which the US economy has been unimpressive over the last decade.

Trump’s focus on the repatriation of US manufacturing could indeed see US factories benefit from the falling price in robotics, which may undercut emerging and developing countries’ former competitive advantage, which was founded on comparatively low labour costs. Also, more US companies are beginning to recognise that through offshoring they lose out on higher-level design learning, which cannot be completely divorced from the production process. “Manufacturing amounts to about 60 to 80 per cent of industry R&D – it’s an innovation sector,” concludes Mr Muro.

At present, the US workforce lacks the skills required to undertake the highly technical and specialist work of future manufacturing. Political will and investment will be crucial for the US government, working hand in hand with universities and companies, to train the next generations of manufacturing employees. US spending on public and private training currently trails behind its industrial competitors at less than 1 per cent of GDP.

What of the older, low-skilled workers, who will be gradually and silently managed out of the workforce? Mr Muro proposes a “universal basic adjustment benefit”, a package of measures including wage insurance, job counselling, relocation subsidies, and other financial and career help that would aid individuals to transition from unemployment or retrain. It will be a hard sell, he acknowledges, given Republicans’ traditional opposition ideologically to all permutations of welfare, but even conservativism, Mr Muro argues in a forthcoming paper, is demonstrating the potential to be “disrupted by technological disruption”.

As the digital revolution makes dislocation and job insecurity the new normal, conservative parties for whom the idea would have until recently been anathema are again embracing the idea of an industrial strategy and long-term planning to ease the pains of transition.

Researchers at the Oxford Martin School have found that automation is already causing political polarisation and swings to the left and right. Voting behaviour is begging for bold answers. Lest we forget, at the beginning of the first industrial revolution, frustrated weavers burned down the factories containing the equipment that replaced them; by its end, their grievances had been rationalised into a more coherent objection, The Communist Manifesto.

The rise of automation

Productivity levels