Carl Frey and Michael Osborne’s seminal 2013 paper on The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs To Computerisation? offers hope for some and concern for others. The study takes the Keynesian view that the “discovery of means of economising the use of labour [will] outrun the pace at which we can find new uses for labour”. It makes concrete predictions of the probability that specific roles will be automated.

The paper finds that those filling human resources transactional roles, such as payroll and time-keeping, are almost certain (97 per cent) to become unemployed as technology takes over. Crucially, Frey and Osborne forecast that those in management roles are extremely safe in their positions, with just a 0.055 per cent chance of being replaced by technology.

HR then is on a course to become far less transactional and far more strategic. But what skills will the HR director of 2030 need to pack for this journey into the future?

The 2030 workforce will be very different to that of today.

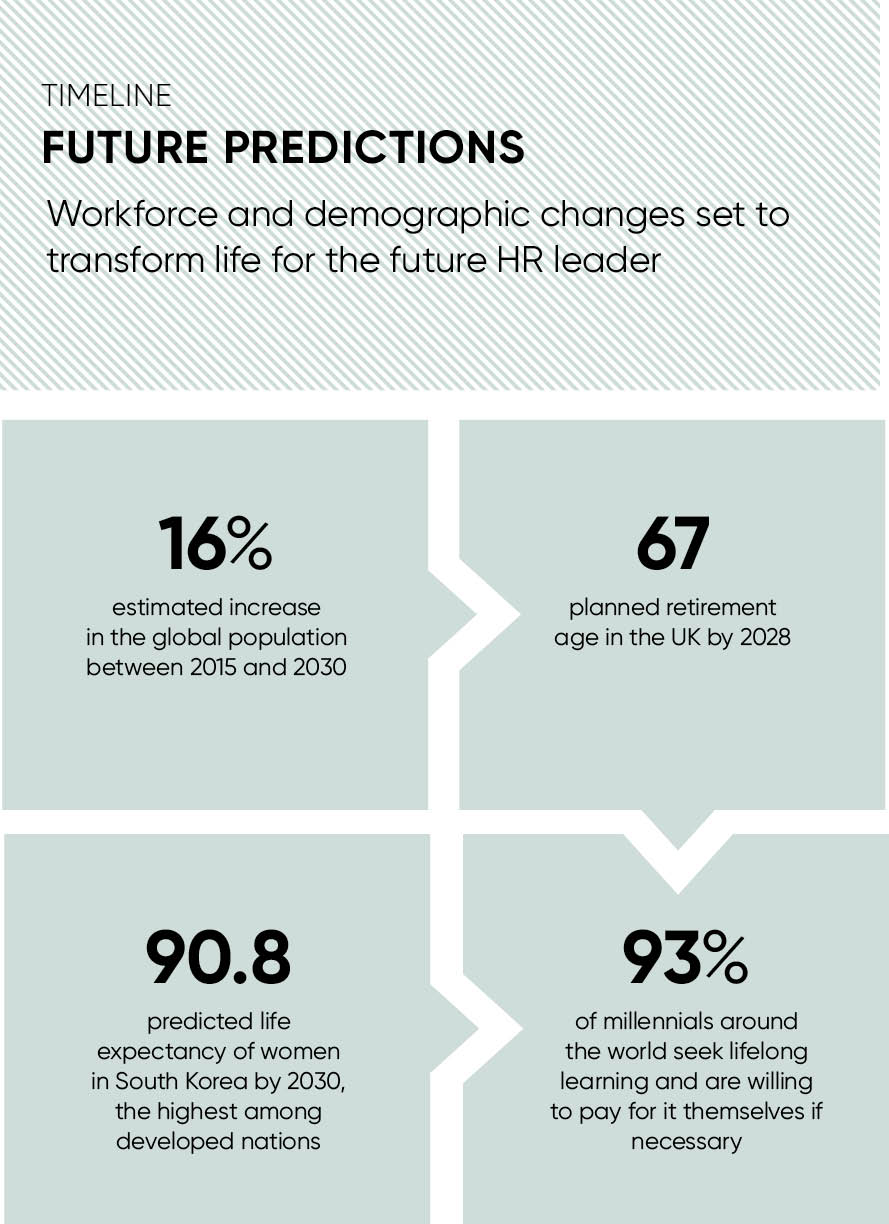

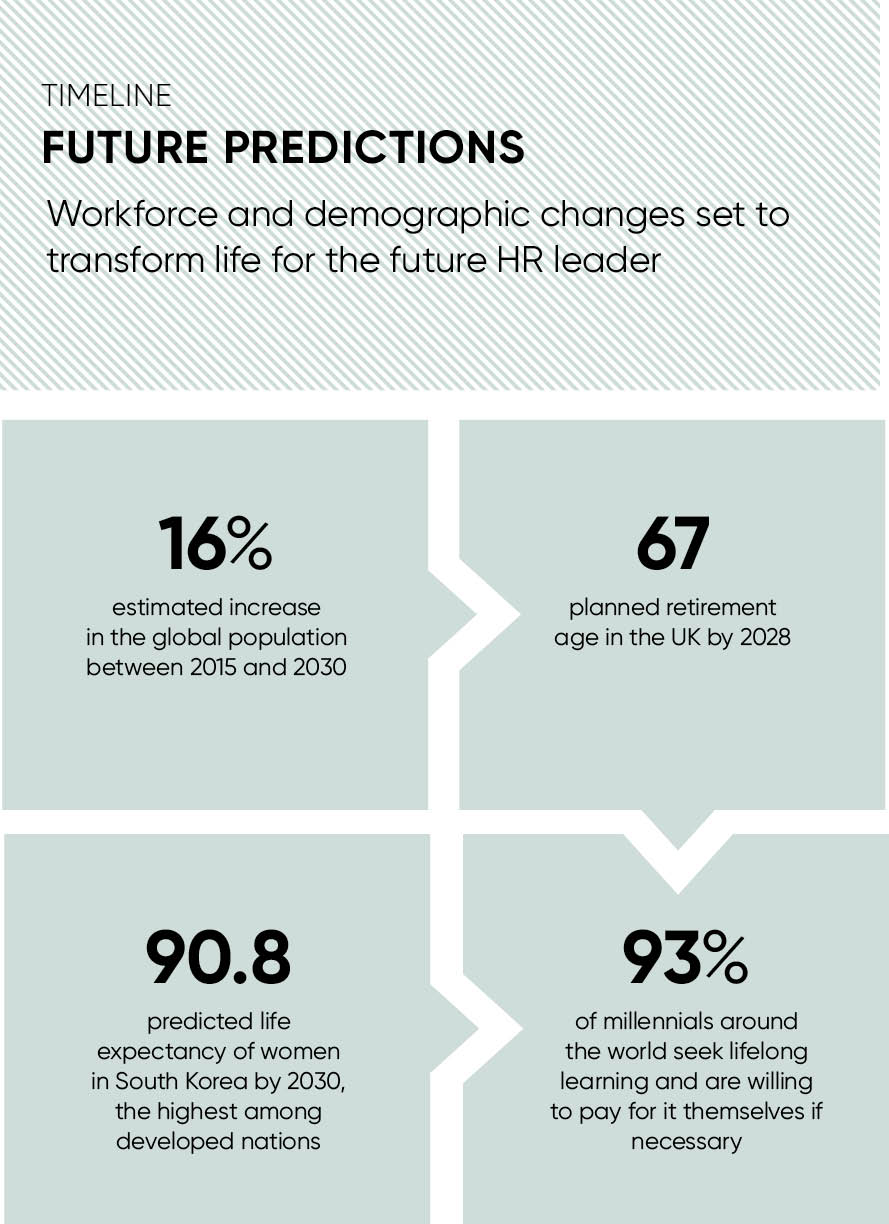

The United Nations forecasts that the world’s population will have grown to 8.5 billion in 2030, compared with 7.3 billion in 2015. A falling fertility rate in Europe will enable economies to reap a demographic dividend as the proportion of people of working age rises, potentially allowing health and education to be better funded.

There will also be a higher proportion of older people working. Life expectancy is set to increase in all major countries by 2030 with women born in South Korea expected to live an average of more than 90 years. Retirement age is certain to increase as a result and will have reached 67 in the UK by 2028.

The HR professional of 2030 will have to consider the implications of managing more older people, many with managed health conditions that might have been fatal in earlier decades. There will be some HR challenges. Business travel will no longer be primarily a young person’s game, and directors will need to consider the need potentially for more emergency assistance and higher business travel insurance premiums.

The job-for-life culture of the last century, already ailing, will be dead and buried by 2030. McKinsey says that between 20 and 30 per cent of the working population is already working in the on-demand or gig economy, and these contingent workers are likely to become more commonplace as companies aim to rightsize themselves for future economic conditions where disruption will come faster and from every part of the world. For the future HR chief, the key challenge will be to engender company loyalty.

Faster business cycles and new disruptive technologies mean that the core competency required of employees will be the ability to adapt to swift change.

Technology is likely to make finding the right talent easier and also reduce unintentional bias in the recruitment process

A recent survey by Manpower of 19,000 millennials around the world and their expectations from the workplaces of the future revealed a commitment to continuous skills development, with 93 per cent of respondents seeking lifelong learning and willing to pay for it themselves if necessary.

Technology is likely to make finding the right talent easier and also reduce unintentional bias in the recruitment process.

CVs as we know them may finally expire, replaced instead by a sort of LinkedIn on steroids. It will instead be a living-and-breathing record of a person’s experience, skills, competencies and potential, drawn from a collaborative pool of sources, including the individual, their past and current employers, and their social connections.

As a result of this smart-matching, workforces are going to become far more diverse than today and people skills, counter-intuitively, may become more important as technology becomes omnipresent, and cross-cultural and cross-generational teams become the norm.

The future HR chief will need to be workplace agnostic. As the population becomes more urbanised, the upward pressure on property prices will continue to grow, making large central offices unaffordable and contributing to the rise of remote working. The idea of teleworkers using immersive virtual reality headsets to interact with their colleagues from around the world is not so far fetched.

The challenge for HR will be one of replacing water-cooler moments and after-work drinks with interactions that are meaningful and conducive to better working.

Employees of the future will be analysed in unprecedented detail and in real time. Cisco predicts that by 2030 there will be half a trillion smart devices in the internet of things. Every aspect of productivity will come under scrutiny as a result.

Those employees whose roles have not been automated will be monitored in real time to ensure they are happy; it could be a case of monitoring inflexions in their voices for stress as they carry out a search that would have been typed in earlier years. Behind the scenes, an algorithm will note this and automatically provide them with a different task that is more suited to their current state of mind.

In 2030, people skills will still be required, but data science and forecasting skills, and the ability to design and tweak algorithms, will be even more essential. As a result, the HR director of the future will have an unprecedented ability to drive competitive advantage and lay claim to a strategic seat on the board.