Football clubs might not be the first businesses to spring to mind when it comes to conversations about human capital and risk, but they probably understand it a lot better than most.

Build a team around a few key players and, if they leave or can’t play, disaster inevitably awaits. That’s why Leicester City’s recent Premier League triumph was such a shock. It involved just 23 players – the fewest in the league.

Physiotherapists say it was having the fewest injuries of any top-flight club that really saw them through. Indeed, according to a report this month by human capital analyst Organisational Maturity Services, Leicester would actually be in the bottom half of the table if ranked on their human capital index. This is an AAA to D scale that rates organisations in terms of key management systems, such as talent pools and succession planning, and predicts long-term, sustainable success.

Human capital

Paul Kearns, chairman of the Maturity Institute, which developed the scale, points out that this type of ranking acknowledges the well-known human resources cliché, which says “people are a company’s greatest asset”, and so by definition people pose risks too.

But while grading goes some way to comparing how organisations manage their human capital, he says putting a number on the balance sheet about the people component of risk is still the Holy Grail of HR and accountancy.

Build a team around a few key players and, if they leave or can’t play, disaster inevitably awaits

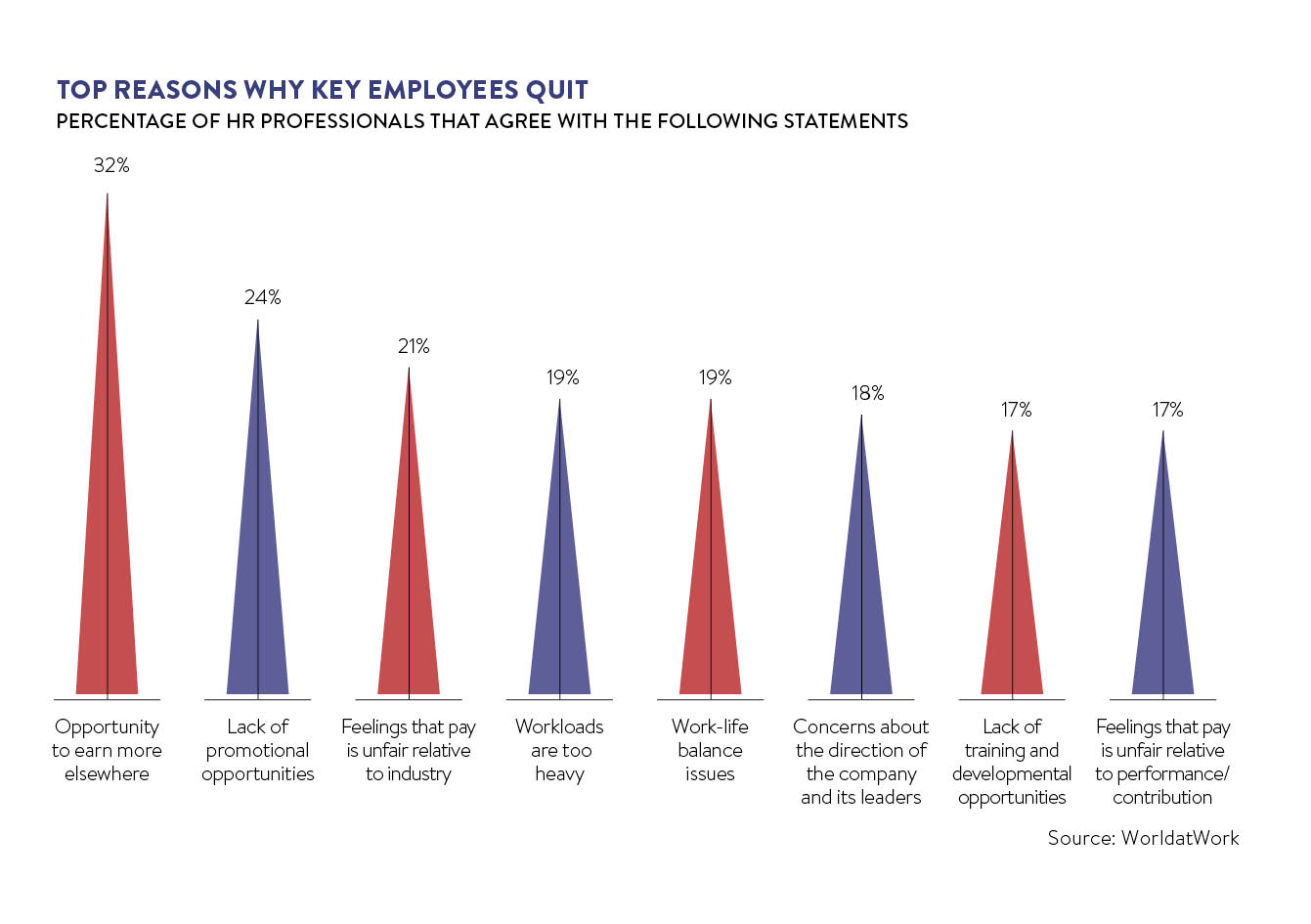

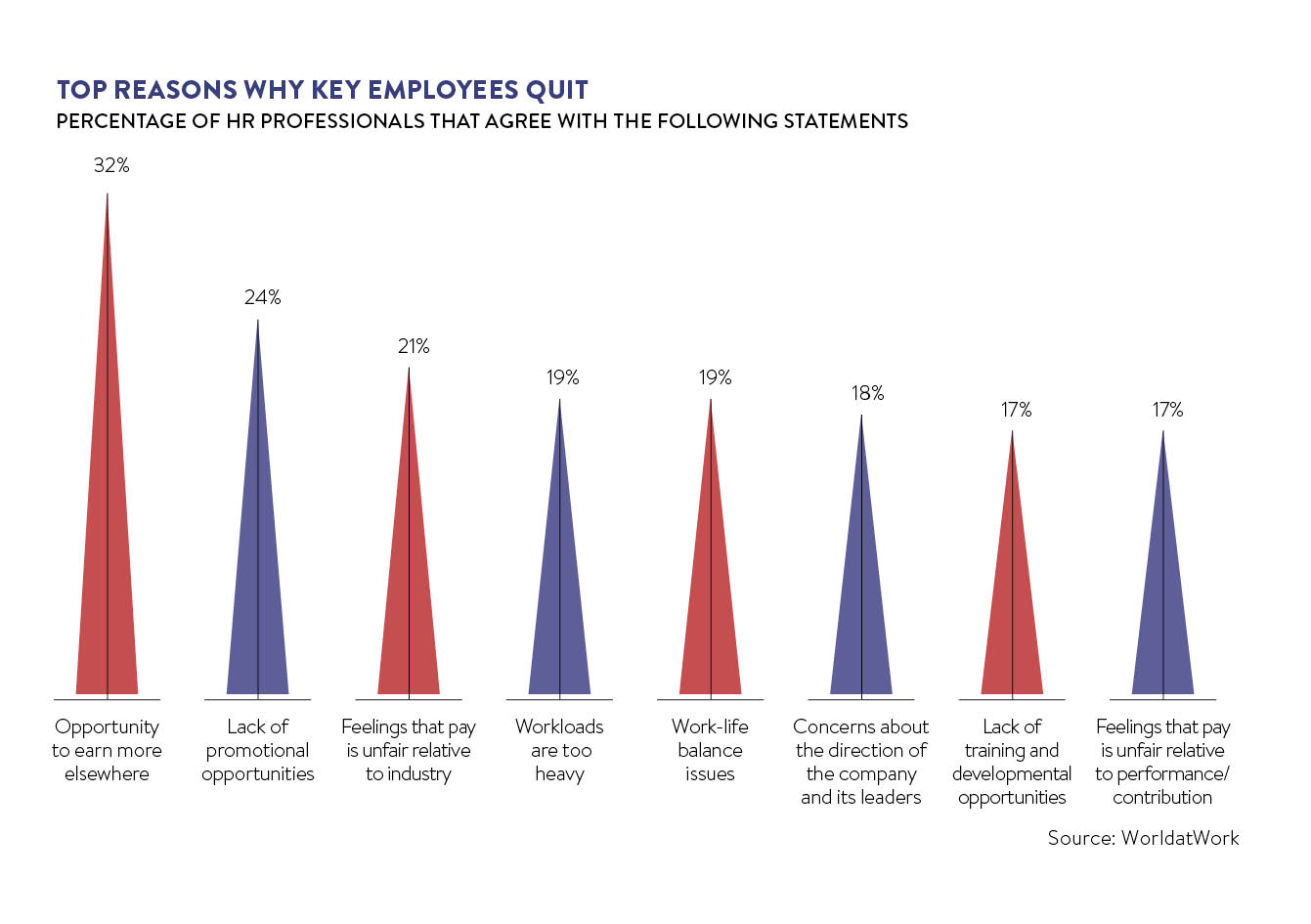

“Added value stuff is fairly easy to demonstrate,” says Mr Kearns. “Training adds value, while reward structures that aid retention also add value. But risk is always ‘lost’ value and that’s always hard to calculate.”

According to the Harvard Business Review, 80 per cent of a company’s value is its people, but while the departure of a chief executive of finance director can trigger stock market revaluations, these are nearly always short lived and don’t account for the contribution (or lack of it) from the rest of the staff.

“Markets still seem trapped using the ‘leader as hero’ way to either value or devalue a business, even though they know it’s not the case,” says Catherine Shepherd, development consultant at Roffey Park Institute. “There is hardly ever talk about the whole human capital in a business and the impact of people making mistakes, turning against their employer or leaving – all things that do actually happen.”

[embed_related]

Mapping behaviour

Infosys is one of the few businesses quoted as making some attempt at putting a value in areas like this. It uses the famous 1971 Lev and Schwartz accounting model to calculate employees’ collective worth. But even this is a formula based on the present value of future earnings, adjusted for such things as the probability of employees’ death, separation, retirement or training.

Today this model would fail to account for, say, the social network value of people and the positive or negative impact those with lots or a few social media followers might add to a business. It also doesn’t consider the implications of what some argue is an even greater contributor to risk ¬– organisational culture.

“There’s a phrase ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’,” says Rob Noble, chief executive of The Leadership Trust. “Leaders have a role creating a common set of behaviours and expectations, and this must be a part of assessing risk, but it’s also hard to pin down.

“At this level of granularity, other things like whether you have diverse teams or good female representation also feed into this because diversity is known to avoid group-think and challenge decision-making that might fly in the face of the culture of the business.”

Mr Noble believes that in most companies it’s not lone wolves who pose the greatest risk, but rather it’s the environment in which employees are expected to work that has most impact and this is partly set by the executive.

An organisation that is trying to make sense of all of this is enterprise applications provider Unit 4. Kara Walsh, chief human capital officer, says: “My job title reflects the CEO’s view people are assets and so I do calculate risk as I see it, including the risk of people leaving us, especially those in R&D.

Productivity as risk

“We also look at the risks to the business of having people not performing as high as those being more productive. This is a big change in dialogue around people compared with what was happening 20 years ago.

“People are intangible assets, but other things we measure, like time to productivity, makes them tangible. We would say productivity is actually our greatest area of risk. To lessen it, we’ve reduced the time it takes new hires to get up to speed time from nine to six months.

“A project I’m looking at now is productivity gaps and extrapolating a value for this in terms of the risk of not improving it going forward. Taking this approach means we put a value-add on things like training, which moves our performance needle along. The simple fact is, if you class your people as an asset, you have to treat them like any other asset. That means investing in them to grow value.”

Experts argue taking a company-wide, systemic approach to risk, rather than trying to find it in one or two people that might cause damage, is a much better overall defence.

“Investment management company Black Rock will now rank the organisations it thinks are better to invest in according to diversity metrics, while analysts are also looking at things like the risk around not paying staff a living wage,” says Mark Quinn, UK head of talent at Mercer.

“HR has long had things like strategic workforce planning, succession planning and talent pipeline programmes, which will all mitigate the risk of key people leaving, so combining the two will be more common. Predictive analytics will start to look at what the path for staff is if you hold on to them and all this feeds into the people side of risk.”

But while experts might still be divided on how to quantify risk, one thing they are agreed on is the irrelevance of options such as key-person insurance, which firms can take out to protect themselves against risk.

“This only encourages bad management,” says Mr Kearns. “Insurance won’t keep people, so paying it is simply a cost to a business. It’s far better to look at your own management systems.” Mr Quinn agrees: “It’s disaster recovery only and not a solution to risk.”

Human capital