When pensions make newspaper headlines it is almost always for negative reasons. The massive stock market losses of the COVID crash, which saw the FTSE100 lose around a third of its value over the first three months of 2020, have been no different. So how has this latest shock to the system influenced attitudes to pensions and how have market players adapted in meeting that most important of all pension industry challenges of maintaining public trust?

Pension providers are adopting increasingly sophisticated risk management strategies to protect savers from the worst of stock market falls and preserve that hard-earned public confidence.

The coronavirus pandemic is the latest in a series of black swan events, unforeseen cataclysmic events that create stock market turmoil and have huge repercussions for the value of assets within pension schemes.

Richard Butcher, chair of the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association, says: “I sense there are probably more big risk factors now, the increasingly violent reactions of the weather and climate change, feeding into the migration crisis and broader environmental issues.

“Historically no one has been good at modelling risk successfully, but pension professionals are now pricing in risks we can’t anticipate. We can’t put names on these risks because we don’t know what they are. But we can model the impact of extreme scenarios on investment portfolios.”

How market participants performed

Diversification, also known as not putting all your eggs into one basket, has been around as a concept for years. Defined contribution (DC) pension schemes are addressing pension industry challenges of concentration of assets by ramping up the breadth of what they invest in, going beyond equities, bonds and property, and bringing in private equity and infrastructure.

Diversification protected DC investors during the COVID crash. While the FTSE100 fell 34 per cent between January 1 and the market low of March 24, workplace pension schemes suffered much lower drops. Analysis of seven of the UK’s biggest master trust pension schemes by industry publication Corporate Adviser shows younger savers, those with 30 years to retirement, experienced drops of 20 per cent over the period.

The process of lifestyling, where older savers are moved into less risky assets to protect them against market shocks as they approach retirement age, delivered even more downside protection. The average older saver’s pot fell just 4.2 per cent over that period. Diversification and lifestyling have been key to addressing these pension industry challenges.

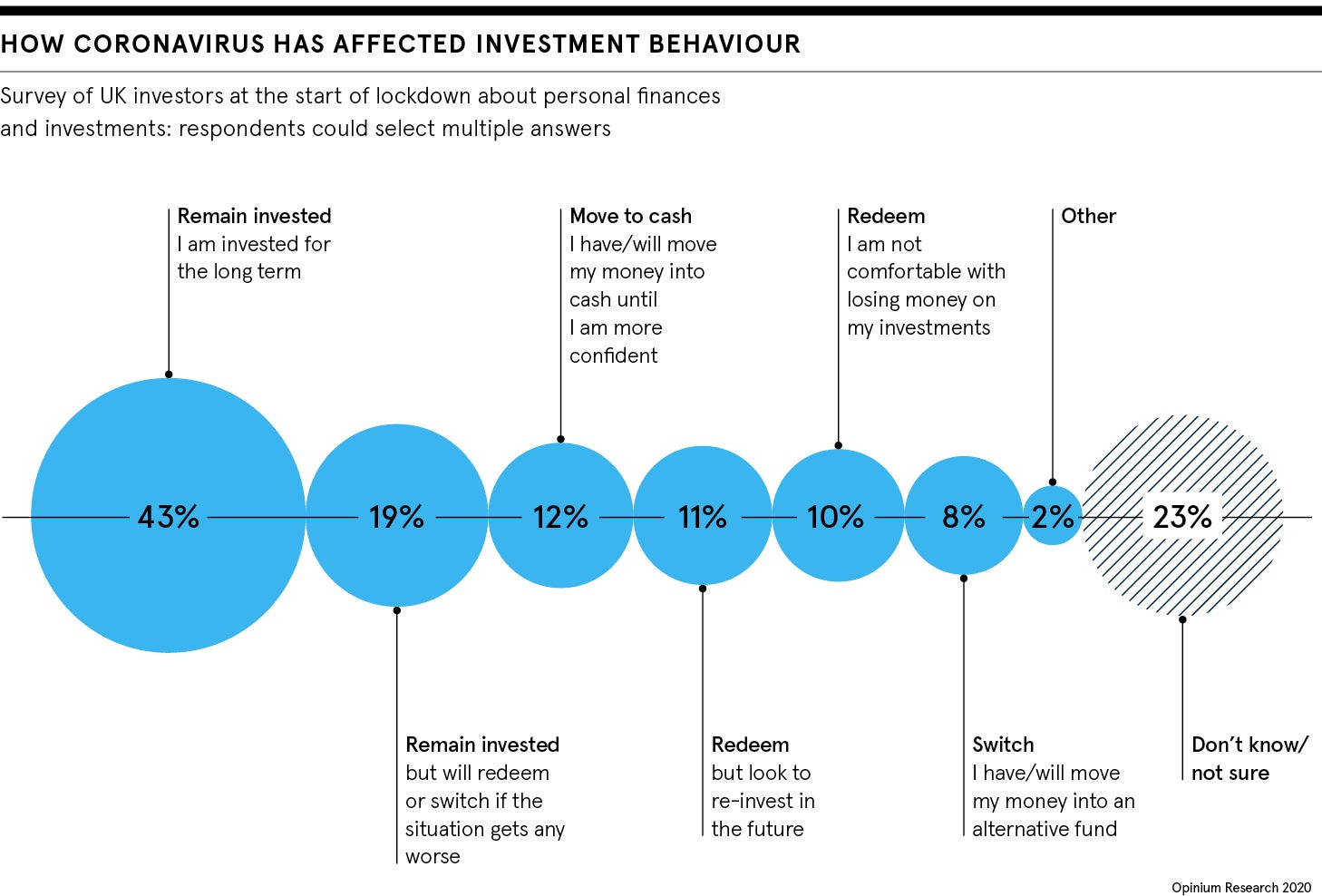

Robert Cochran, senior corporate pension specialist at Scottish Widows, says investors generally responded calmly to the stock market turmoil and trust in the system has largely been maintained. “When the stock market tumbled, we saw a big spike in customers looking to switch out of their funds to more secure options,” he says.

“Had they done so they would have locked in their losses and missed out on the rebound. Because pension providers are getting better at communicating digitally with customers, we were able to successfully explain why volatility is not necessarily a bad thing for long-term savers and the majority stayed invested.”

Confidence key to weathering pension industry challenges?

That decision to stay put has turned out to be the right one. The rebound in markets has seen the great majority of DC pension funds recover all their COVID-crash losses, with the average workplace scheme delivering a positive return for younger savers of 0.9 per cent in the year to June 30. Older savers, within a year of state pension age, registered a positive return of 2.8 per cent.

Mark Futcher, a partner at pensions consultancy Barnett Waddingham, says: “The big message during the stock market turmoil was to provide reassurance that the strategies in place were designed to cater for precisely this sort of volatility. The industry beefed up its messaging around this and was largely successful; scheme members and employers were broadly reassured.

“At the same time schemes also made it easy for members to temporarily stop their contributions if necessary, recognising that some households might be struggling financially.”

The big message was to provide reassurance that the strategies in place were designed to cater for this sort of volatility

Andrew Cheseldine, chair of the board of trustees of the Smart Pension Master Trust, adds: “Markets fell significantly and they bounced back pretty quickly. Lifestyling did its job for older savers. And even if there hadn’t been an immediate rebound, for those with 20 or 30 years until retirement, it doesn’t matter if the market drops. Falling markets are actually an opportunity for long-term savers to buy assets cheaply.”

Pressure on DB schemes

Pension industry challenges in the area of defined benefit (DB) schemes are different. Some schemes have become more precarious as the assets held within them have fallen in value. Legal & General Investment Management’s DB Health Tracker index, which reflects schemes’ asset to liability ratio, the demographic risks in the scheme and the likelihood of the sponsoring company becoming insolvent, showed the average DB scheme could expect to pay 91.4 per cent of members’ benefits at March 31, down from 96.5 per cent at the end of 2019. But by June 30, some ground had been clawed back, with the index rising to 93.5 per cent.

Cheseldine says: “There are many well-funded schemes out there with the resources to weather the storm. But in struggling sectors, such as aviation, retail and hospitality, there may be schemes whose sponsoring employer goes under and it seems inevitable these will end up in the Pension Protection Fund.”

However, no high-profile schemes have fallen over yet and trust in DB schemes has not been eroded so far, say experts.

Climate change is seen by the government as one of the greatest of pension industry challenges. New regulations force both DB and DC schemes to challenge long-term investment risk, by making them evidence the science behind their investment decision-making, particularly in relation to environmental, social and governance factors, with a specific focus on climate change.

Industry experts say it is too early to say whether this latest in a series of seemingly increasingly frequent “once-in-a-lifetime” events will change attitudes to retirement. But they do report a longer-term trend towards pensions becoming just a part of a bigger, broader retirement plan.

Cheseldine concludes: “This trend will continue to be driven by the tighter restrictions on the amount you can pay into your pension. Interest in ISAs (individual savings accounts), particularly the Lifetime ISA, is growing, both among employers and members of the public. And for many people, residential property, whether their own home or buy to let is increasingly seen as part of their retirement plans.”

When pensions make newspaper headlines it is almost always for negative reasons. The massive stock market losses of the COVID crash, which saw the FTSE100 lose around a third of its value over the first three months of 2020, have been no different. So how has this latest shock to the system influenced attitudes to pensions and how have market players adapted in meeting that most important of all pension industry challenges of maintaining public trust?

Pension providers are adopting increasingly sophisticated risk management strategies to protect savers from the worst of stock market falls and preserve that hard-earned public confidence.