Sustainable investing is enjoying its moment in the sun. After years of platitudinal rhetoric, investment markets at last appear to be putting their money where their mouth is. The wolf of Wall Street has discovered its soft side.

ESG, the acronym du jour, is everywhere. Investor webinars, investment indices, management reports, analyst notes, all are now singing the virtues of environment, social and governance themes.

It’s not just public-relations spin, either. Cold, hard cash is finding its way into sustainable investing. New research from the US Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment indicates that around one in every three dollars of the $51 trillion in assets under management is now subject to at least one ESG criterion.

This shift in capital allocation should be seeing investment dollars moving away from irresponsible companies and into those championing a more ethical form of capitalism. But is it? And, if not, what changes might help it to do so?

Relying on ESG indices can be counter-productive

Amid the ESG excitement, sceptics abound. One is Lynn Forester de Rothschild, chairman of the UK wealth management fund E.L. Rothschild and a fervent convert to “conscious capitalism”. For Forester, the lack of exactitude as to what qualifies as ESG has left the door open to a number of anomalies.

She gives the example of Air Products and Chemicals, a US firm dedicated to the sale of carbon-intensive gases and chemicals. But because the firm is commercialising hydrogen, it’s a darling of ESG markets. In contrast, Denmark-based Ørsted, the world’s leading offshore wind power producer, is marked down because of some legacy fossil fuel assets.

The examples point to how counterproductive relying on ESG indices can be. “Unfortunately, when you look into what is owned by the majority of ESG-branded ETFs [exchange-traded funds], they are virtually the same stocks as conventional ETFs, so they make precious little difference,” she says.

It is a verdict endorsed by a recent research briefing on sustainable investment funds by market analyst firm Massif Capital. The report argues the hotchpotch approach to stock selection means investors remain exposed to the non-financial risks that ESG supposedly prevents.

Unfortunately, what is owned by the majority of ESG-branded funds is virtually the same as conventional ones

Worse, it keeps money from going to the problem-solvers. Take cement, which given its huge footprint, most ESG investors agree is a major no-no. As a result, however, capital for progressive firms in this in-demand $312-billion industry to look into clean alternatives is effectively being choked off.

According to Massif Capital’s managing partner Will Thomson, investors need to adopt a more transitional mindset. Instead of identifying benign companies, he argues, impact-minded investors should be picking firms in problematic sectors that boast a clear strategy for change.

“We cannot recreate the economy without carbon-intensive businesses as if we had a blank sheet of paper; it is crucial to work with the businesses we have,” he says.

Data deficiency problem for investors

Part of this more selective approach is an upgrade in data. Recent years have witnessed a boom in the market for ESG ranking and analytics, but determining which stocks are genuinely committed to sustainability issues is still a stab in the dark for many investors.

The problem is two-fold. On the one hand, lack of standardisation means investors are frequently left comparing apples with oranges. And because disclosure of non-financial information is still largely voluntary, they often find themselves with too few apples or oranges even to count, let alone compare.

Change is afoot, however. A collection of recognised standards is beginning to emerge – the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board is a good case in point – while legislators are also getting tougher on disclosure requirements. In the UK, for instance, fiduciary regulations enable pension funds to specifically accommodate ESG factors.

Time horizons are equally important. At present, financial information looks almost exclusively backwards. But to exert impact, sustainable investing needs forward-looking data as well. So says Amer Khan, European managing director at Entelligent, a data platform that integrates climate-risk information. It is important to have hard data on how a company will reduce emissions in the future, not just on how it has reduced them in the past.

Khan is also an advocate of innovation in trading mechanisms themselves. He points to the example of smart beta ETFs, which use a rules-based system for selecting investments to be included in the fund portfolio. To date, those rules typically apply to predetermined financial metrics. So how about a “climate beta” equivalent for listed equity stocks?

Time to take a more active approach

His suggestion gets to the crux of sustainable investing’s current lack of impact: namely, passivity. The great appeal of tracking funds is its hands-off approach. Investors opt for an index that meets their mandate, issue instructions to the index manager and then essentially sit back and twiddle their thumbs.

Impact doesn’t work that way. It requires investors to be more proactive, asking questions of management, exercising their voting rights, pulling out of certain sectors, investing in others. The upside of equity indices is the trillions of dollars at play; minuscule shifts can create enormous waves.

Tribe Impact Capital is one of a growing number of investment houses determined to take a more explicitly active position. The UK wealth management firm invests exclusively in high-impact firms. With the satisfaction of making a tangible difference, however, comes high management oversight and a small pool of capital.

It may not be Tribe’s chosen strategy, but Fred Kooij, the firm’s chief investment officer, still believes sustainable investing can make a mark in mainstream investment markets. He takes heart from advances in transparency and reporting, as he does the emergence of “well thought-through, informed and managed indices”.

Oxymoronic as it may sound, these developments hold out hope for those who want to do more in the passive space.

Understanding sustainable investment definitions

ESG

Now a fixed part of the investor lexicon, the acronym ESG stands for environmental, social and governance issues.

According to the Financial Times Lexicon, ESG is “used by investors to evaluate corporate behaviour and to determine the future financial performance of companies”. The base assumption is that how companies behave with respect to non-financial issues impacts on their future profitability.

What constitutes a material ESG issue is yet to be defined. The European Federation of Financial Analysts Societies suggests nine broad areas, including energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions (environment), employee training and absenteeism (social), and litigation risks and corruption (governance).

ESG investing covers almost all asset classes, from equities and fixed income through to highly tailored private investment vehicles. It contains within it a panoply of different sub-categories, including socially responsible investing, impact investing and values-based investing. One of the stand-out characteristics of ESG funds is their long-term focus, with ESG investors working to multi-year cycles rather than quarter to quarter. Far from sacrificing profits, however, research indicates that ESG funds frequently outperform the market over the medium and long term.

SRI

SRI stands for socially responsible investing. One of the more established forms of ESG investing, it grew out of the concerns of ethically-minded investors, starting with the Quakers and later championed by the likes of church pension funds and university superannuation funds.

Given its origins, SRI is historically associated with a tactic known as negative screening. This practice sees industries deemed unethical or irresponsible removed entirely from portfolios. Typical examples include companies dealing in tobacco, gambling, alcohol, pornography and arms. These became labelled as “sin stocks”.

Over the last few decades, SRI investors have adopted more nuanced approaches. One popular tactic is to select the most ethical or responsible performers in specific industries, so-called best-of-class companies. Another approach is to constructively engage with firms, offering them an opportunity to change key policies or practices rather than immediately excluding them.

These developments reduce the moral associations of the term “responsible”, which have historically made mainstream investors uncomfortable, but which shareholder activists have embraced. The vogue over recent years has been towards less deterministic descriptors such as sustainable and resilient.

Central to SRI is a belief that capital can generate positive social and environmental outcomes as well as, not instead of, financial returns. Debate continues regarding the profitability of SRI. A recent survey of existing research by RBC Global Asset Management concludes that SRI does not necessarily result in lower returns, but evidence for its generating above-average returns remains inconclusive.

Impact investing

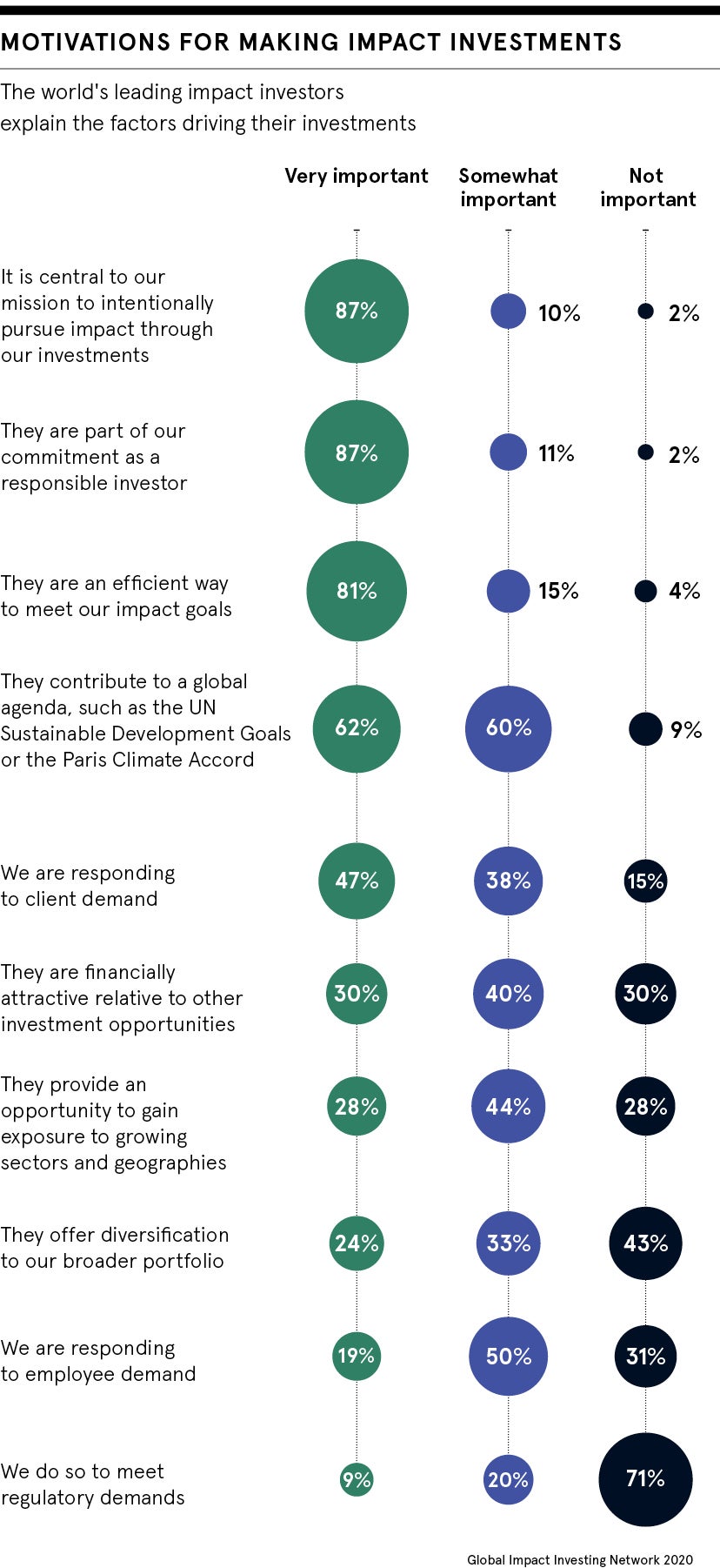

As the term suggests, impact investing represents a highly active form of ESG, with a particular focus on generating positive social and environmental outcomes. Depending on their mandate, impact investors may often settle for a lower-than-average or slower rate of financial return in exchange for high impacts.

“You can deliberately choose to go into lower-return funds to gain a high social return,” says Stephen Muers, chief executive at UK impact investor Big Society Capital. “Although some asset classes such as affordable housing funds offer a financial return similar to mainstream asset classes.”

Given their focus, impact investors typically choose much more specific social or environmental metrics than conventional ESG investors. The very first social impact bonds, for example, were issued a decade ago with the goal of reducing reoffending by former prisoners in the UK. Around 138 similar social impact bonds have been issued since then.

Moves are underway by the Impact Management Project to design an agreed framework for measuring and assessing the outcomes of impact investments. Veteran UK investor Sir Ronald Cohen is also championing an approach to valuing companies, known as impact-weighted accounting, that incorporates social and environmental costs or externalities.

Sustainable investing is enjoying its moment in the sun. After years of platitudinal rhetoric, investment markets at last appear to be putting their money where their mouth is. The wolf of Wall Street has discovered its soft side.

ESG, the acronym du jour, is everywhere. Investor webinars, investment indices, management reports, analyst notes, all are now singing the virtues of environment, social and governance themes.