The cash machine celebrated its 50th birthday this year; it was 1967 when Barclays opened its first ATM in Enfield. More than 80 per cent of cash withdrawn from banks is obtained through cash machines, but it is cash itself that could be on the way out.

After all, it is two years since the UK passed the tipping point of more electronic than cash payments. And by next year, more than 20 per cent of online transactions are likely to be made through mobile devices, according to PwC.

Nor is the UK alone. Governments across the world are pushing the drive towards a cashless society, hoping to reduce issues such as fraud or funding for terrorism, decrease the black economy and improve tax revenues. Last November, for example, the Indian government abolished 500 and 1,000 rupee notes overnight in a bid to stem fake currencies and corruption.

“Government plays a big part in becoming cashless,” says Senthil Ravindran, head of the fintech lab for banking and financial services at Virtusa, a technology company. “It is easier for a government to tax a salary going through a bank; digital payments help a government collect tax.”

Financial institutions are just as keen as the traceability of electronic payments brings huge benefits, from automatic reckoning to a greater knowledge of the customer. For the consumer, it is convenience and speed that are the draw.

According to Andrew Stenton, managing director at Civica Payments, a technology company: “People expect to make payments easily and securely, at a time which is convenient and via a channel of their choice. Cash is becoming an increasingly expensive commodity to manage, for all parties involved. In fact, today, half of Britain’s population keeps less than £5 on their person at any one time.”

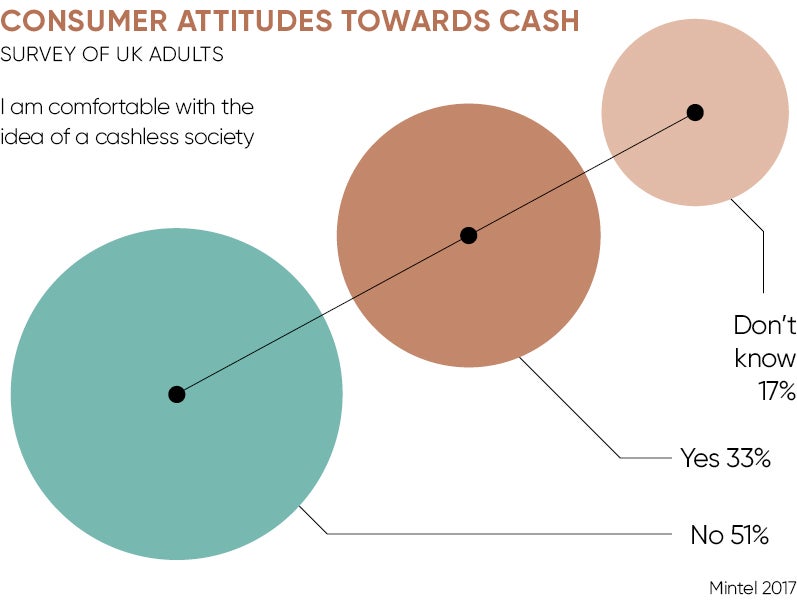

But not everyone is so happy. According to a recent report from Mintel, a market research company, only a third of consumers would be comfortable with a cashless society. There are about two million people in Britain without a bank account, according to the Financial Inclusion Centre. Such individuals cannot access the cheaper costs that come with direct debits or online shopping and as a result on average pay an extra £1,300 a year.

In India, according to a report from the World Bank, as much as 97 per cent of transactions involve cash, a factor that could account for the pushback that greeted the demonetisation.

There are, of course, certain jobs that rely heavily on cash. Any sector where tipping is a common practice will find its economics changed by the use of purely electronic payments, where it can be hard to ensure the gratuity goes to the right person.

More alarmingly for some, reliance on electronic payments brings a lack of privacy, both for good or for ill, and a potentially dangerous reliance on technology which has, after all, been known to go wrong. Lose your wallet to a thief and you lose your cash, but lose your password to a cyber criminal and you might lose your life savings.

But does the absence of a bank account and the decline of cash always mean the poorer half of society misses out? Not necessarily. Look at the rise and rise of the mobile payments industry. M-Pesa, a mobile phone money transfer service, has revolutionised payments in countries such as Kenya and Tanzania. Services such as Pingit and Paym in the UK are side-stepping not only cash, but plastic as well.

“The cashless revolution has three interconnected elements – e-commerce, digital cash and smartphones,” says Simon Black, chief executive at PPRO, an electronic money specialist.

This is a massive change in behaviour that we’re going through; there will be bumps along the way

In the UK, however, about 25 per cent of people don’t have smartphones and broadband access can be patchy, especially in some rural areas. That combination can make mobile payments difficult, leading to financial as well as digital exclusion.

Mr Black says: “This is a massive change in behaviour that we’re going through; there will be bumps along the way. It’s a gradual transition and the way to protect people who are resistant to change is to make sure there isn’t a cliff edge where suddenly you can’t pay with cash.”

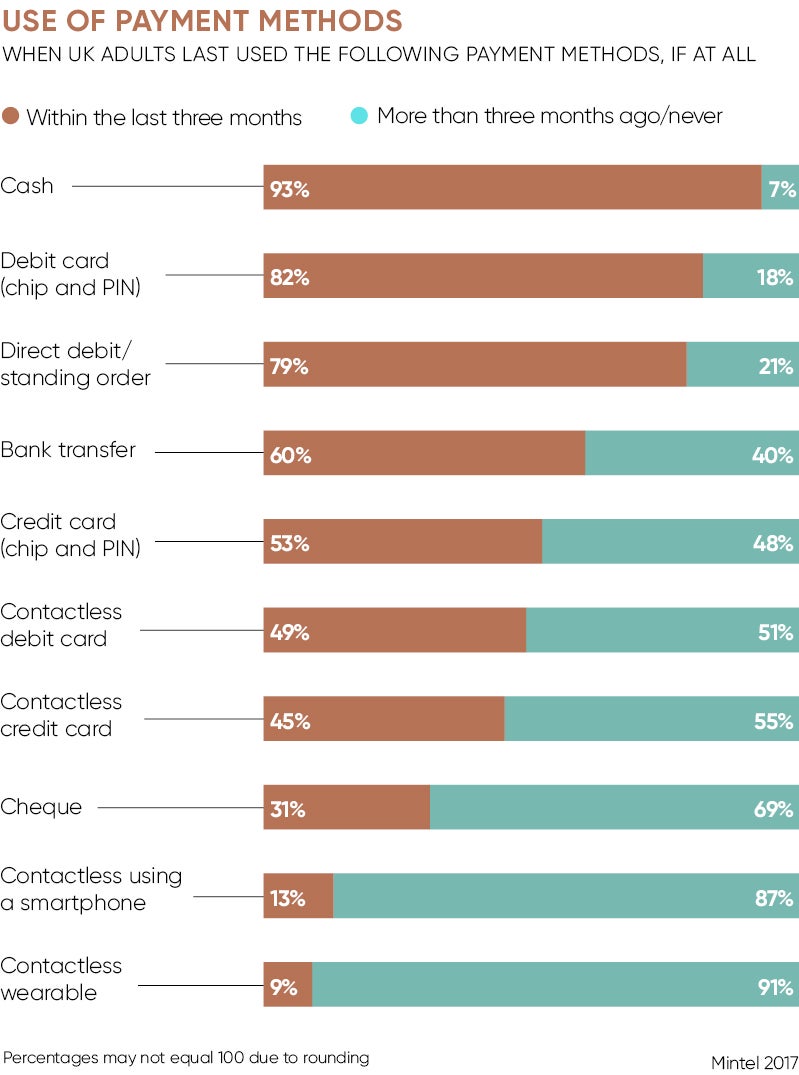

Five years ago there was a lot of resistance to the tap-and-pay idea; it took time for everything to fall into place, from the issuing of new cards to the upgrading of retailers’ card machines. Now contactless payments are the norm for many of us.

One country that stands out in the cashless revolution is Sweden, where the use of cash has fallen by 40 per cent since 2009. Bills and coins now represent a mere 2 per cent of Sweden’s economy. Last year the central bank, the Riksbank, began an investigation, due to be completed at the end of 2019, into whether to issue an e-krona.

According to deputy governor Cecilia Skingsley: “The Riksbank will continue issuing banknotes and coins as long as there is demand for them in society.” But she adds: “If the market can make use of the new technology to launch new and popular payment services, why shouldn’t the Riksbank be able to do the same?”

The appetite for e-krona appears to be limited. One survey, from Tieto, a Swedish digital payments firm, found that only a tenth of those polled were in favour.

The fact that contactless smartphone payments don’t offer added convenience over contactless card payments will remain a significant barrier to uptake

So it seems there is no one-way street for payment systems. “Despite widespread ownership of both smartphones and cards, many people continue to show a preference for cash,” says Patrick Ross, senior financial services analyst at Mintel. “It’s clear there isn’t all that much difference in terms of the convenience of these options. The fact that contactless smartphone payments don’t offer added convenience over contactless card payments will remain a significant barrier to uptake.”

Cash still has its uses and for some countries, including the UK, is an indispensable part of life. Others, regardless of the level of economic development, are happy to dispense with it. The replacement for cash may be plastic, but there again may be mobile phones. The advent of virtual currencies may add an extra element to the debate. But in the end, the convenience and reliability of cash makes it hard to give up.

The cash machine celebrated its 50th birthday this year; it was 1967 when Barclays opened its first ATM in Enfield. More than 80 per cent of cash withdrawn from banks is obtained through cash machines, but it is cash itself that could be on the way out.

After all, it is two years since the UK passed the tipping point of more electronic than cash payments. And by next year, more than 20 per cent of online transactions are likely to be made through mobile devices, according to PwC.

Nor is the UK alone. Governments across the world are pushing the drive towards a cashless society, hoping to reduce issues such as fraud or funding for terrorism, decrease the black economy and improve tax revenues. Last November, for example, the Indian government abolished 500 and 1,000 rupee notes overnight in a bid to stem fake currencies and corruption.

“Government plays a big part in becoming cashless,” says Senthil Ravindran, head of the fintech lab for banking and financial services at Virtusa, a technology company. “It is easier for a government to tax a salary going through a bank; digital payments help a government collect tax.”