As the UK’s overseas territories prepare to make public the owners of all their registered companies by the end of 2020, business experts are debating how to balance calls for transparency with the kind of privacy often prized in finance.

In what is seen as a major victory for financial transparency campaigners, earlier this year the UK government was forced to agree to sanctions and anti-money laundering legislation when Conservative and Labour MPs combined to back the registration of beneficial ownership.

The new legislation builds on a pledge in 2013 by then-prime minister David Cameron and is designed to stem the global passage of so-called “dirty money” in the wake of the Panama Papers scandal, which exposed a rogue offshore finance industry.

Who will be impacted by these new rules?

British Overseas Territories (BOTs) – 14 areas including financial centres the British Virgin Islands, Anguilla, Bermuda, Montserrat and the Cayman Islands – are to set up public ownership registers by the end of 2020. Any failure to introduce the required registers will risk having them imposed by the UK government.

The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill does not apply to the crown dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man, where the UK parliament does not have legal powers to impose its will.

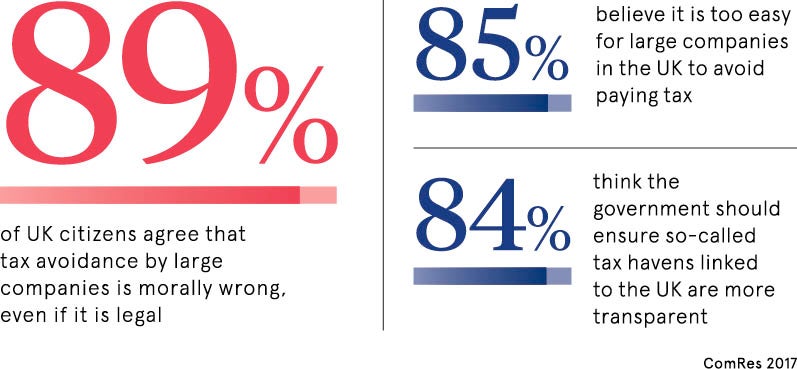

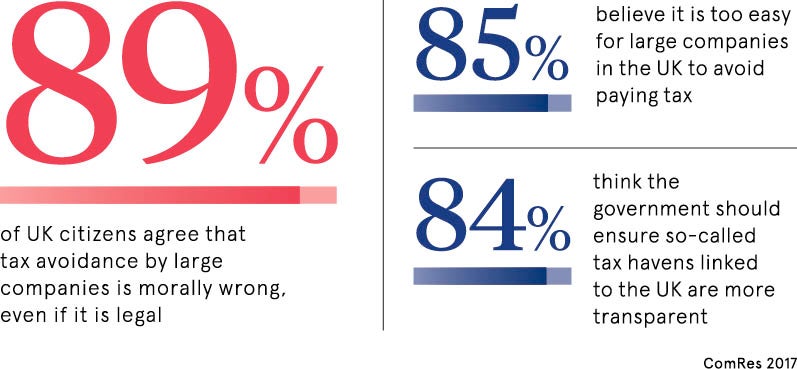

The new legislation is seen as part of a drive to collect billions in taxes from UK contractors that use offshore tax-avoidance schemes. HM Revenue & Customs estimates that around 50,000 people are engaged in foreign-based tax-avoidance schemes.

British Overseas Territories have largely resisted the new legislation in favour of a data exchange network called the common reporting standard, which was launched last year with more than 100 countries participating in information-sharing. The network uses over 3,200 treaties between more than 100 countries to swap ownership information with tax authorities.

British Overseas Territories fear consequences of legislation

The new act threatens to strain the relationship between London and certain British Overseas Territories, particularly those who warn of consequences to business and employment in financial centres such as Bermuda, and Turks and Caicos Islands. The BOTs, which have a combined population of 350,000, say an end to tax secrecy could undermine their attraction to financial services companies that depend on investors seeking privacy.

Cayman Islands premier Alden McLaughlin warned the territory was weighing up a legal challenge and described the decision as “reminiscent of the worst injustices of a bygone era of colonial despotism”.

According to Lorna Smith, interim executive director of BVI Finance, the British Virgin Islands currently generates around £3 billion a year in tax revenue for the UK and supports 150,000 jobs. “Our view is that a public register of beneficial ownership is not a silver bullet for improving transparency,” says Ms Smith. “It is not about who can see the information; it’s about the information being verified, accurate and therefore useful to law enforcement agencies. A verified register is a far more robust and effective approach to ensure transparency than an unverified public register.”

Judith Tyson, research fellow at the Overseas Development Institute in London, says: “One of the issues at stake is how to balance transparency and privacy. Those in favour of the new legislation would argue that if companies haven’t done anything wrong, or have nothing to hide, they shouldn’t be worried about the scrutiny of public registers.

“But this needs to be balanced against the right to privacy and the need to ensure that investments, especially to the poorer countries where the protection offered to investors from offshore financial centres is key, is not reduced.”

Does legislation compromise rights of British Overseas Territories?

British Overseas Territories argue they have already introduced private central registers of ownership, which are accessible to UK law enforcement and tax authorities. They claim the move to make them publicly available by December 2020 will force investors to move their money to more secretive territories. One offshore centre told MPs that any move to introduce public registers could cost £72 million in lost revenue a year.

Legislators from the British Overseas Territories also claim the UK parliament’s action infringes their constitutional right to oversee their own domestic legislation. In May, in the British Virgin Islands, more than 1,000 people marched in protest against any enforced changes in current transparency legislation.

The risks for dirty business ending up in bright daylight are increasing, and that means greater accountability and greater deterrence

Campaigners say full financial transparency improves human rights and better safeguards democratic ideals. “Financial transparency laws are good news for the protection of human rights and democracy across the globe, and bad news for tax dodgers, money launderers and kleptocrats,” says Markus Meinzer, director at the Tax Justice Network. “The risks for dirty business ending up in bright daylight are increasing, and that means greater accountability and greater deterrence.”

The key is balancing privacy with transparency

Ms Tyson adds that another solution would be for countries to legislate as a bloc to tackle criminality in finance. “It would be more advantageous for countries to work together to enforce universal standards. This would lead to a more synchronised approach, although its implementation would require funding from all the stakeholders especially for poorer countries. The benefit would see more taxes collected in both developed and developing nations.”

Finance specialists say the drive for transparency marks an attempt to distinguish between legal business centres and illegal tax havens. “The danger is that certain investors will be deterred by the invasion of their privacy,” says Simon Airey, corporate crime and investigations partner at international law firm Paul Hastings. “There are many perfectly legitimate reasons why companies and individuals prefer to keep their affairs confidential. The problem is that there are others who want to do so for the wrong reasons.”

“This is obviously a controversial issue and certain territories consider the imposition of the new laws to be an affront, but they will ride the storm and continue to flourish. It is the recidivist tax havens that will wither and die.”

Who will be impacted by these new rules?