The role of pension scheme trustees is under the spotlight from regulators concerned about their ability to look after members’ interest as the industry goes through rapid change and growing complexity.

The Pensions Regulator and Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) have each expressed concerns about the role of trustees and whether more professionalism, tighter scrutiny and increased regulatory power would benefit members.

What are pension trustees?

Trustees manage £1.8 trillion of assets on behalf of 32 million members, according to the Pensions Regulator, but the demands on them are rising, from technical issues over funding to increasing regulation and an ageing population increasingly reliant on private pension provision.

They are responsible for ensuring a pension scheme, either defined benefit (DB) or defined contribution (DC), is run properly and members’ benefits are secure.

Boards range in size from one trustee to nine, with an average of three, and can include professionals, trustee companies and lay members who may be individuals, company or member-nominated trustees.

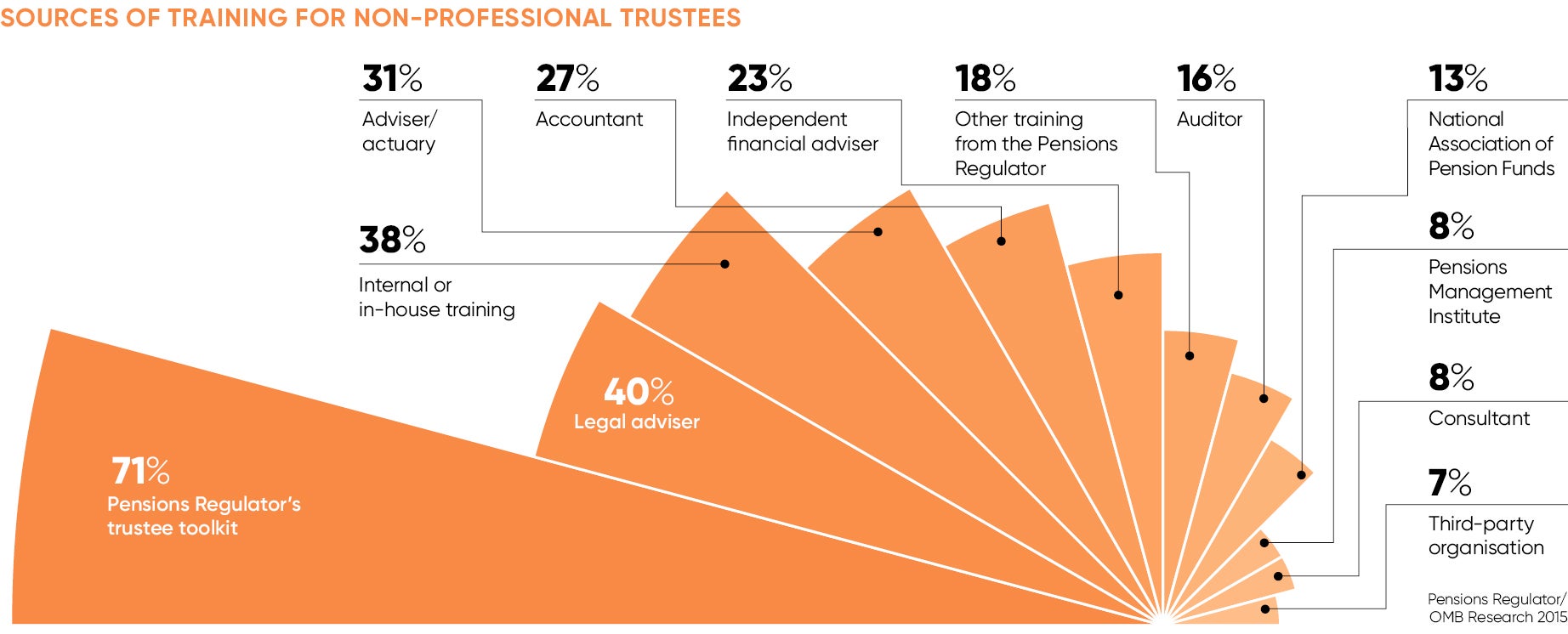

They work with advisers such as lawyers, actuaries and investment managers, and are legally obliged to have a knowledge and understanding of the law on pensions. Aside from a basic Pensions Regulator “trustee toolkit”, training and qualifications are largely voluntary.

Their role is described as “important and difficult” by the Pensions Regulator in its 21st-Century Trusteeship and Governance discussion paper, which has been the subject of heated debate since publication last year and will be a key influence on future developments.

It describes effective trusteeship as the key to underpinning good outcomes for members and says it was reassured by the “dedication, skill and tenacity” displayed by many boards.

But it also warns that not all boards met good standards of governance and administration, stating: “In short, poor governance and administration is not a victimless phenomenon – it’s bad for members and it’s bad for employers too.”

The DWP also entered the fray this year with its Green Paper on the Security and Sustainability in Defined Benefit Pension Schemes.

It called trustees the “first line of defence” for members, pointing out that average DB pensions of £7,000 a year were a vital source of income for 11 million people.

Among the issues raised by the DWP are whether trustees are sufficiently skilled in making decisions about investment in a sophisticated market, whether they need more training and whether there should be a drive for more professionals on boards. It says, if small schemes fall short of required standards, they should consider consolidating with others.

Industry response

So far industry response has been varied. The Pensions Regulator says its consultation showed a consensus that good governance was essential and all types of trustees made a valuable contribution.

It notes concerns that unnecessary regulation could place a burden on well-run schemes as could mandatory training for lay trustees, and it recognised disagreement about how to set minimum standards for professionals and who should oversee any regime of compulsory qualifications.

Joe Dabrowski, head of governance and investment at the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association, says smaller schemes tended to have lower levels of good governance because of pressure on resources and expertise, but not all big schemes were well run.

He adds: “We are sympathetic to the view that there should be more demanding standards for anyone claiming to be a professional trustee. There’s a lot of room for improvement.”

Nita Tinn is a director of Independent Trustee Services, a firm of professional trustees, and sits on the council of the Association of Professional Pension Trustees (APPT). The APPT carried out a consultation about bringing in a recognised qualification for professional trustees, which Ms Tinn’s company supported, but the overall view of its members was that now is not the right time. The APPT is currently working with the Pensions Regulator on developing a set of protocols that professional trustees can adhere to.

Ms Tinn says: “I think there is a need to have a clear demarcation line between professional and lay trustees. If you call yourself a professional, you should adhere to a set of standards. There’s a push to bring up standards, but if we don’t have a kite mark, how is a buyer of services to know what they are getting?”

Wayne Phelan, managing director of PS Independent Trustees, with two decades’ experience sitting on boards, says: “I think you need a good blend of lay and professional trustees. The more diversity of thinking you can get the better.”

Not only is there a limited pool of professional trustees, it is getting hard to find the volunteer lay trustees who not only bring a detailed knowledge of a company’s history, but can challenge advisers by asking the simple questions members are concerned about.

Bruce Allison, 70, a retired marketing director, is one of four member-nominated trustees of Volvo Corporate Trustee and sits alongside four company-nominated trustees and a professional chairman.

He says: “In theory we could run it without a professional, but they bring a broader experience of other funds and what is going on in the industry.”

Regulators may have stepped back from any immediate major changes to the demands on and scrutiny of trustees, but the pressure to drive up standards is growing.

The challenge facing regulators and the industry is how to secure agreement on getting the best out of lay and professional trustees without making their responsibilities so onerous that recruiting skilled and dedicated people becomes even more difficult.