We love clothes and the clothing industry loves us. Our predilection for fashion and the purchases we make keep half a million people in jobs in the UK. It’s a £26-billion industry, according to the British Council. But the sands are shifting in the fashion industry and there’s a growing awareness of responsibility on both sides.

Consumers are cautious about the way the industry works and the wastage and poor conditions under which workers toil to bring them the latest catwalk fashions on the high street. Retailers are also worried that, lured by cheap prices and abundant designs, we’re shopping ourselves into unsustainable debt, particularly at a time when coronavirus is crashing the economy. Responsibility is the watchword for all parties, whether they’re buyers or sellers.

The changes brought about in consumer behaviour by the pandemic have given retailers the ability to understand better their customers’ needs and habits. It has also given the industry time to pause and reflect on how it can help promote a sustainable future for all.

Fast fashion comes at a cost

Fashion-conscious consumers can quickly rack up big bills buying the latest items, all while churning through their wardrobe at a worrying rate. Retailers are cottoning on to the risks and helping consumers become smart shoppers. As well as simplifying and reducing lines to put out whole-year collections, rather than regular new releases with the change of seasons, retailers are offering shoppers new services.

Many have partnered with payment provider Klarna to offer buy-now, pay-later services, allowing people to try items without accumulating interest for a short time before either returning the garment or paying for it by text message. Laybuy, a similar scheme, works with other retailers to reduce impulse purchasing and improve sustainability.

Other businesses forgo garment ownership entirely. Companies such as Hire Street encourage people to try rather than buy items, renting luxury fashion for a short time before returning it, instead of buying a dress to sit unworn at the back of the wardrobe for 11 months of the year. Yet business-led initiatives are only part of the solution as consumers need to change, too.

Online retail’s impact on the industry

Between 1963 and 2009, the number of deliveries a day remained steady at around one for every ten people. By 2017, it shot up to 2.5 for every ten people as a result of more of us shopping online. More choice, lower prices and the lure of free returns meant ecommerce ballooned. It was a buyer’s world and we knew it.

But untrammelled growth and a fast fashion economy couldn’t continue forever. Every online delivery of new clothes to offices and homes sent carbon emissions rising. The miles travelled in the delivery chain compounded the issue and that’s before we even thought about sending back the four sizes of the same item we also ordered to ensure the right fit.

COVID-19 has made people stop and re-evaluate everything… What has worked is pressure from civil society on issues

Ecommerce has changed attitudes to how we buy as one in ten purchases made in stores are returned at most, compared to one in four online. DPD, one of Europe’s biggest delivery companies, saw the number of returned items it handled double between 2017 and 2018.

Online shopping continues to rise: internet sales as a percentage of everything we buy have increased 50 per cent in a year, according to the Office for National Statistics. Yet consumer attitudes are changing.

“We’re in a transition where I think COVID-19 has made people stop and re-evaluate everything,” explains Rachel Kan, fashion sustainability specialist at Circular Earth, a consultancy. This could have a major impact on the way the fashion industry responds, says Luke Smitham of Kumi Consulting. “What has worked is pressure from civil society on issues,” he says.

Demanding responsible sourcing

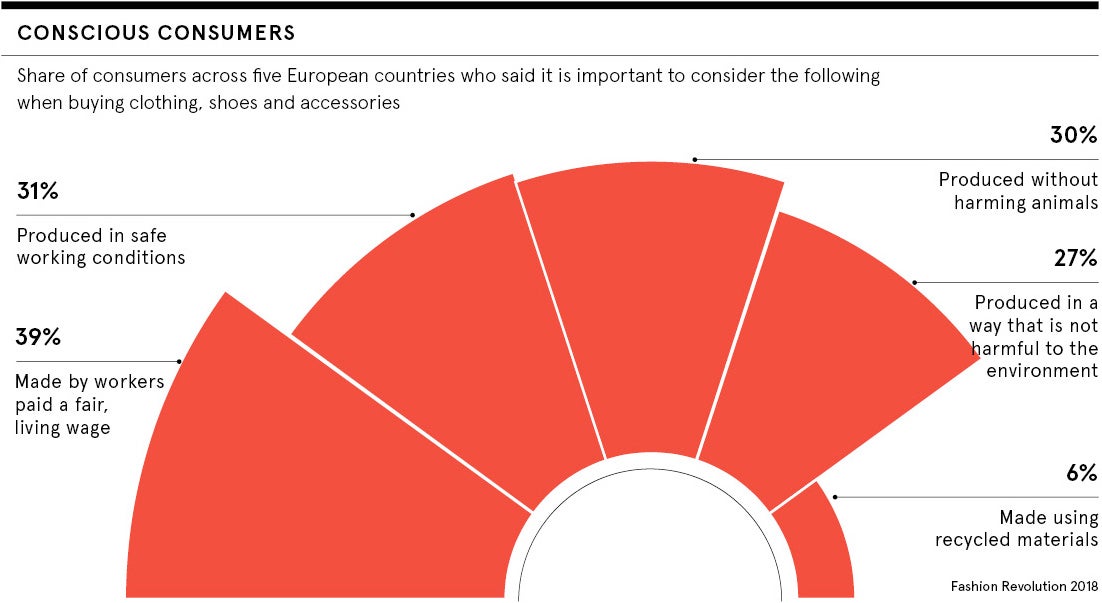

We’re growing increasingly aware of the impact our shopping habits have on the planet and the people who live on it, and consumers are determined to make a change. There are moves up and down the process and across the fashion industry to adapt to responsible consumerism, and to suit consumer demand for more ethically sourced and environmentally friendly processes.

One of the ways brands are trying to make clearer the impact of their clothing on the planet is by increasing transparency of the supply chain. Since the 2012 fire in a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which killed 117 people, consumers have signalled their unhappiness at cheap clothes produced in unsafe conditions.

Headlines about the plight of Uighur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang province, who help supply much of the world’s clothing brands with cotton and other textiles, have also given consumers pause for thought. And stories about garment workers in Leicester, paid less than the minimum wage producing clothes for Boohoo, have thrown a light on the human impact of fast fashion.

“On the luxury fashion side, you can have shorter supply chains with more control because you’re making fewer pieces,” says Smitham. “You can go back to traceability.”

But it’s easy to complete the paper trail while still bending the rules and maintaining a clean audit. What’s needed is the adoption of cutting-edge technology like blockchain, which can track a cotton fibre from source through to manufacture of a garment.

“The consumer now wouldn’t know by looking at a garment where it has come from, where the yarn is from, where the cotton is grown,” says Kan. “With blockchain you’d be able to know what sheep the fleece in your jumper is from.”

Embracing traceability and circularity

Companies make some concessions to traceability and transparency, but they are often piecemeal. “As a consumer, it’s really hard without a consistent amount of information across companies to make that decision as to who you should or shouldn’t go to,” says Smitham.

Likewise, technology can help head off issues with endless returns and the iteration of designs before they’re even manufactured. There’s also waste when retailers order samples of clothing in different sizes before making purchases. 3D technology, which maps clothes onto different sized bodies, can prevent that happening. Shorter supply chains and tech-enabled insights can take the guesswork out of ordering garments.

“A good season is generally 60 to 80 per cent sell-through and the rest is incinerated or sat at the back of the shop as dead stock,” says Kan. “Going towards something more virtual, and some of the catwalk stuff recently becoming virtual, is a [business] model.”

Perhaps the most responsible action is making the fashion sector a more circular economy by reusing and recycling clothes. Rapanui, a fashion brand that set out to tackle wastage in the 100 billion items of clothing bought worldwide, has expanded to become Teemill, an on-demand, sustainable fashion business making new products from recycled ones.

It’s a business model Kan would like to see others follow. “Each company has to evaluate their own brand’s way of being,” she says. “Bigger brands will have to go to circularity in the first instance.”

We love clothes and the clothing industry loves us. Our predilection for fashion and the purchases we make keep half a million people in jobs in the UK. It’s a £26-billion industry, according to the British Council. But the sands are shifting in the fashion industry and there’s a growing awareness of responsibility on both sides.

Consumers are cautious about the way the industry works and the wastage and poor conditions under which workers toil to bring them the latest catwalk fashions on the high street. Retailers are also worried that, lured by cheap prices and abundant designs, we’re shopping ourselves into unsustainable debt, particularly at a time when coronavirus is crashing the economy. Responsibility is the watchword for all parties, whether they’re buyers or sellers.

The changes brought about in consumer behaviour by the pandemic have given retailers the ability to understand better their customers’ needs and habits. It has also given the industry time to pause and reflect on how it can help promote a sustainable future for all.