In 2016, a tumultuous year of global change, ‘fake news’ became a cultural phenomenon, with the dissemination of incorrect yet influential information propelled by social media. Unquestionably, the peddling of deceitful falsehoods, which appeal to emotions and trigger confirmation bias, impacted upon the outcomes of the United States presidential election, Britain’s Brexit referendum, and many other epochal campaigns across the world – and statistics prove it.

A BuzzFeed News study revealed in November that during the final three months of the US presidential campaign the best-performing fake news articles posted on Facebook enjoyed greater digital traction than the top-ranking stories published by the main 19 news outlets in America, including the New York Times, Washington Post, Huffington Post, and NBC News. Indeed, hoax articles generated 8,711,000 shares, reactions, and comments, compared with 7,367,000, en route to Donald Trump’s crowning.

President Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, warned that very month: “If we are not serious about facts and what’s true and what’s not, if we can’t discriminate between serious arguments and propaganda, then we have problems.” Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, went further and in March said: “[Fake news] is killing people’s minds. [It] is a big problem in a lot of the world. We are going through this period of time…where unfortunately some of the people that are winning are the people that spend their time trying to get the most clicks, not tell the most truth.”

Cook said in his interview with The Telegraph that in order to combat fake news “there has to be a massive campaign”, and he added: “We must try to squeeze this without stepping on freedom of speech and of the press, but we must also help the reader.”

The backlash against the epidemic of fake news – a term that has morphed in meaning, with the White House incumbent using it to describe news allegedly concocted by the enemies in the media – has begun in earnest. Slowly but surely technology giants are taking steps to limit the proliferation of such destructive and potent content. But is enough being done?

The rise of fake news

Searching “fake news” (with quotation marks) in Google throws up almost 34 million results, yet a succinct definition is increasing tricky to determine. It is a descendant of ‘yellow journalism’ – a term that originated from a novel, eye-catching cartoon of a snaggletoothed, barefoot youngster called Mickey Dugan who appeared in the February 17, 1895 edition of New York World; the ‘yellow kid’ was a successful experiment in colour printing on newsprint and designed to attract readers.

Now fake news has evolved to become a catch-all phrase for the purposeful attempt to pass falsities for realities, though it is more sinister than parody or satire; it is the zeitgeist version of ‘bullshit’. In essence, fake news is sensationalist, inflated, false content which is generated and disseminated in a bid to mislead for nefarious reasons – such as political or financial gain – or even just for malicious kicks, or rather clicks.

The inexorable rise of social media has spawned ‘clickbait’ headlines atop stories which often fail to live up to their promise and are sometimes unsourced or uncorroborated. Examples include the following: Pope Francis endorses Donald Trump for president; FBI agent suspected in Hillary Clinton email leaks found dead in murder-suicide; and Clinton pays Jay Z and Beyonce $62 million to perform at the Cleveland rally before the election. Closer to home, there was the tale of the ‘miracle’ baby who was rescued from the 16th floor of the stricken Grenfell Tower 12 days after the fire.

Fake news is killing people’s minds

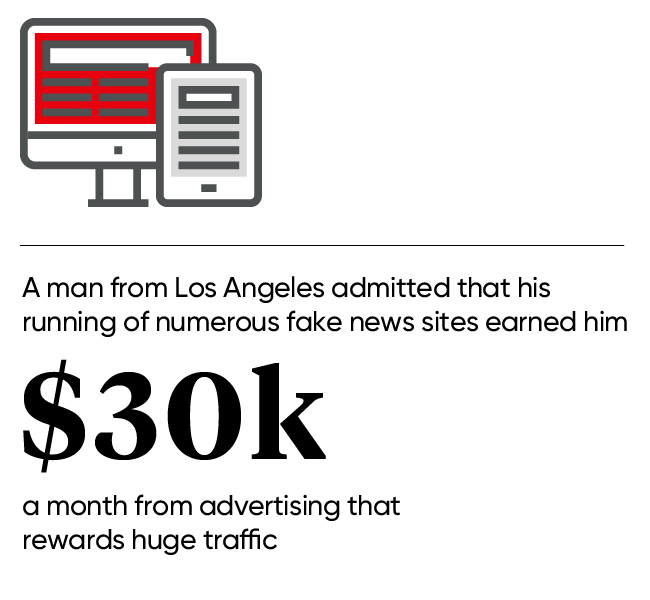

There is money to be made, too, if content goes viral. For instance, last December a man from Los Angeles admitted, on America’s National Public Radio, that his running of numerous fake news sites earned him $30,000 a month from advertising that rewards huge traffic. And Wired reported in February how over 100 fake news sites pushing stories with a pro-Trump flavour were being run by Macedonian teenagers looking to make a quick buck, or ‘denar’ in their case.

Those serving up fake news are getting better at it, and the lines between professional journalism, citizen journalism, and state propaganda are increasingly blurred. So much so, faith in traditional media is dwindling. A Gorkana white paper on the subject, published in June, noted “the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, a global annual study, showed that the media saw the greatest decline in trust of any institution in 2016-2017, falling to just 43 per cent”.

No wonder many British mainstream media organisations have recently founded anti-fake news hubs, including the Independent’s In Fact, FactCheck, Channel Four’s blog, and BBC News’ Reality Check.

Photo on the left is making the rounds on social media. Photo on the right is the original Getty Image. pic.twitter.com/E9aoCI6eCu

— Evan McMurry (@evanmcmurry) July 9, 2017

What else can be done?

The landscape is improving, thankfully. And ironically, Donald Trump’s finger pointing at the “lying” press and the serving up of “alternative facts”, as Kellyanne Conway infamously put it, has fuelled the desire of the American public – and the rest of the world – to work harder for the truth. The main social media organisations, keen to not have their reputations dented, are playing a crucial role, albeit belatedly for some.

Facebook, in particular, has faced heavy criticism for failing to banish fake news stories, and in April German politicians agreed to push ahead with laws that would see the organisation fined €50 million, or £43 million, for not responding to the situation with appropriate action. Coincidentally or not, that same month Facebook users in 14 countries were provided with alerts questioning the veracity of posts, as well as tips to spot fake news.

Adam Mosseri, VP of Product for News Feed at Facebook, said: “False news is harmful to our community, it makes the world less informed, and it erodes trust. All of us – tech companies, media companies, newsrooms, teachers – have a responsibility to do our part in addressing it. We’re exploring ways to give people more context about stories so they can make more informed decisions about what to read, trust and share and ways to give people access to more perspectives about the topics that they’re reading.”

Elsewhere, earlier this year a new section Twitter’s latest annual transparency report announced that the micro-blogging platform had suspended 636,248 accounts between August 1, 2015 through December 31, 2016 in efforts to tackle “violent extremism”. In the last six months of that period, 74 per cent of the 376,890 deactivated accounts were discovered thanks to Twitters own “internal, proprietary spam-fighting tools”.

There is still a way to go, as an Oxford University paper entitled Computational Propaganda Worldwide suggested in June. The research highlighted how vertiginous the road back to a transparent democracy is in some parts of the world, including In Russia where 45 per cent of Twitter activity is managed by “highly automated accounts”.

Will Moy, director of London-based Full Fact, the only independent fact-checking organisation in the United Kingdom, tells Raconteur: “The crisis of confidence around the fake news label is dying down, and that is a good thing. We are still left with some really big problems. We need to do a better job of identifying each individual problem and start having sensible conversations. There is more of a burden on all of us using social media to check what we’re seeing, and as we advise: ‘If you’re not sure, don’t share.’”

In the run up to the recent General Election Google and Facebook, and over 1,900 other donors, helped Full Fact – established in 2010 and now part of the International Fact Checking Network – to publish 100 explainer documents, fact check six party manifestos, among other content that generated over 18.5 million views on Facebook and almost 10 million on Twitter.

Moy believes that artificial intelligence can be used to fight fake news, and continues: “Part of the challenge is technological; how do you keep up with the viral spread of information? It’s something that has been made possible by technology, and keeping up with it has to be made possible by technology as well.

“We’ve got Google integrating fact checks in to news results, and that is really great to see. The key question the platforms have to ask themselves is this: ‘How do we make it easier for people to decide what to trust?’ The tips for spotting false news that we put out with Facebook – things like check whether the URL is a proper news site or fake, look at dates, look at the photos and question whether they have been manipulated – make it much easier to answer.”

In Moy’s opinion “the platforms can do more” and he adds: “Fundamentally, fact checking is the free-speech response to unreliable information – it’s about responding to it with more speech, explaining what’s really going on and I think that is the proper approach to the problem. So as long as the platforms stay on the right side of that, which seems to be absolutely what they want to do, then I think there is room for them to think more creatively about how the product evolves to tackle the key issues.”

The rise of fake news

Photo on the left is making the rounds on social media. Photo on the right is the original Getty Image. pic.twitter.com/E9aoCI6eCu