Ian Baxter likes to draw on 20 years’ experience of the freight industry to argue that staying in the European Union is the logical economic choice for Britain. The founder of a fast-growing, Nottingham-based logistics business, he is, however, in a minority in his own family.

Ian used to work alongside his three brothers in RH Freight, a road transport business created by their father, Neville, until it was sold to international logistics firm Kuehne and Nagel in 2011. Now his father and brothers are backing the Leave side in Britain’s June 23 EU referendum. Ian supports Remain.

This division highlights a problem for the pro-EU camp. While polls suggest most business leaders back Remain, there are enough supporting Leave to confuse the message to voters.

On top of that, the public distrusts executives, especially since the financial crisis. According to pollsters Ipsos Mori, business leaders are trusted by only 35 per cent of those surveyed, coming 20th out of 24 professions. Pro-EU bosses are therefore struggling to have an effect like that of their predecessors in the UK’s 1975 referendum, which ended in a two-to-one vote to stay.

“I think the British people will vote to remain. although I suspect it will be like Scottish vote — a nerve jangler up until the last moment,” says Ian, 49, whose Baxter Freight employs 60 people and does twothirds of its business in continental Europe. “I think we can survive outside the EU, I don’t think the economy is going to tank, but it would be a missed opportunity for growth in the future, putting obstacles in the way of trade that we just don’t need to do.”

[embed_related]

Across the road his elder brother Nigel, 53, is managing director of RH Commercial Vehicles, a Renault Trucks dealership employing 80 workers – a part of the original family firm that he bought back.

“The overriding issue for me is a return of sovereignty to the United Kingdom, allowing us to take back control of our own legislation, our own laws and a democratically elected government,” he says.

Even Ian is no europhile. More than a decade ago he campaigned as part of Business for Sterling for the UK to stay out of the euro. His pro-Remain arguments now are based on trade, inward investment and a belief that the UK needs to co-operate with its neighbours on issues, such as the environment.

He fears withdrawal would result in tariffs and the reintroduction of costly, time-wasting customs clearance procedures. It currently costs £50 a consignment, for example, to move freight between the UK and Switzerland and Norway, which are outside the EU, whereas there are no such restrictions inside. He could pass the cost on, but, he says: “It would be bad for our customers and therefore bad for UK plc. What’s bad for my customers can’t be great for me in the end.”

Nigel, by contrast, believes a trade deal can be negotiated with the EU, that regulation can be reduced and that “we will also have opportunities in the wider world”. He thinks his business is unlikely to be damaged by a withdrawal: “There will be more demand, more growth and therefore I will be positively affected by a UK exit.”

The EU remains by far the UK’s biggest trading partner, accounting for 47 per cent of goods exported and 54 per cent of imports, though exports to non-EU countries have grown at twice the speed of sales to the bloc over the past five years.

Most mainstream economists favour Remain, unlike the late 1990s when they disagreed over whether Britain should adopt the euro

Most trade association polls have produced clear majorities for staying in. The Confederation of British Industry, the UK’s largest employers’ group, found 80 per cent of member companies favour Remain, with only 5 per cent for Leave; even among small and medium-sized companies, 71 per cent wanted to stay.

The Institute of Directors found a majority of 60:30, and the British Chambers of Commerce found a 54:37 for staying in. At the Federation of Small Businesses, the margin was a narrower 47:41. Some domestically-focused businesses feel they suffer the costs of EU regulation without any benefits.

John Longworth, who resigned as director-general of the BCC after backing Brexit in breach of the organisation’s neutrality, says corporate multinationals that favour Remain are talking their own book: “They like complexity in the market because it presents barriers to entry. The EU suits them very well, they can produce expensively and avoid paying tax.”

Mr Longworth argues that if Britain leaves “not much will happen in the short term but over time the performance will get better, we will become more global, we will get more inward investment.” But Terry Scuoler, chief executive of EEF, the manufacturers’ organisation, fears a “significant stutter” to trade and a longerterm drop in economic output if Britain votes to come out. His members back Remain by 61 per cent to 5 per cent against. “It is vital that messages reach voters about the risk to investment and jobs,” he says.

Most mainstream economists favour Remain, unlike the late 1990s when they disagreed over whether Britain should adopt the euro. Estimates of the likely long-term hit to gross domestic product that might result from a more restrictive trading arrangement with the EU range from 5 to 9.5 per cent.

Paul Drechsler, CBI president, says: “The only debate in my mind is whether each household will be £1,000, £3,000 or £4,500 worse off. It’s just not possible that the EU could give us the same opportunity as a non-member that we would get as a member.”

A number of businesses, including foreign-owned companies and supermarkets, have been loath to speak up for fear of being accused of telling people how to vote. Drechsler, however, warns: “I think it is your duty as a business leader to ensure that your customers, suppliers and employees understand what Brexit might mean for them. Do not get to June 24 and say ‘I wish I had spoken out’.”

The bottom line

Campaigners for the UK to leave the European Union, including UKIP leader Nigel Farage and pro-Brexit Tory cabinet minister Priti Patel, have claimed that the UK sends £350 million a week to Brussels. The truth is a little more complicated.

The UK’s notional contribution to the EU in 2015 was £17.8 billion, equivalent to £342 million per week. However, the UK gets a rebate, which was negotiated by Margaret Thatcher. In 2015, that was £4.9 billion. That means that the UK actually sent £12.9 billion, or £248 million per week.

In return, the EU paid £4.4 billion back into projects and programmes in the UK, and around £1.4 billion in support to the UK private sector, which takes the cost to a balance of around £7.1 billion. That is £137 million per week — around £2 per person, per week.

The UK has also committed to spending 0.7 per cent of its gross national income on foreign aid. That means that another approximately £1 billion that goes to Brussels for the EU’s aid budget would have to be spent anyway. Taking that into account reduces the ‘additional’ cost of being a member of the union to £117 million per week, or £1.78 per person, per week.

By comparison, the UK government expects to pay £39 billion in interest on its debts in 2016, an equivalent of £750 million per week.

Unbalanced trade

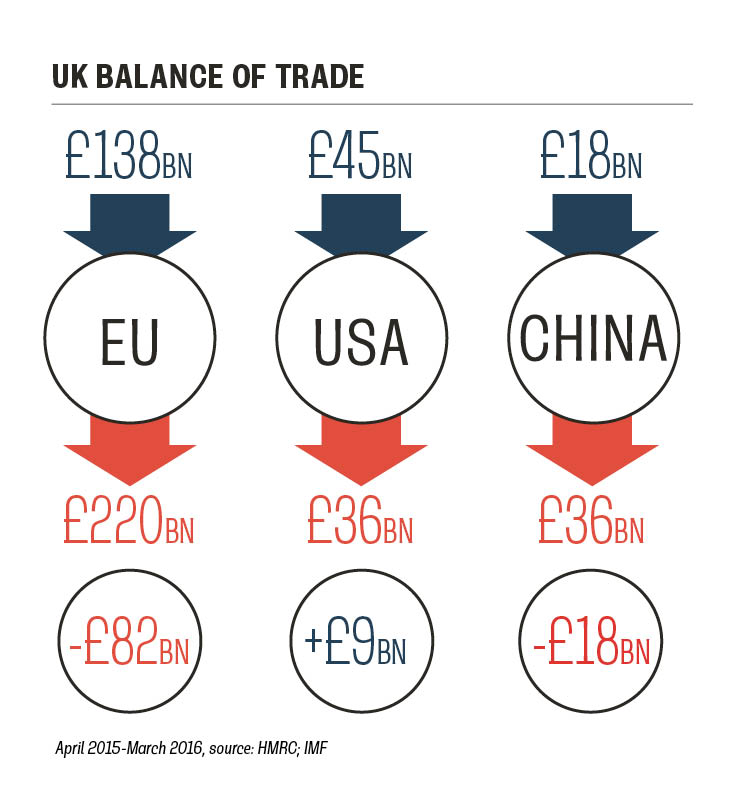

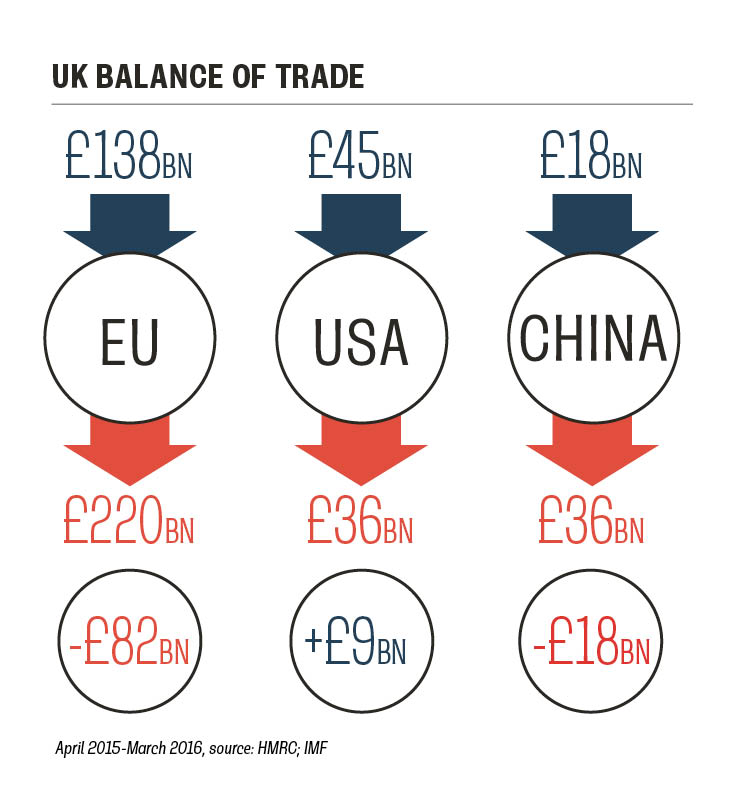

Viewed as a single entity, the European Union is by far and away the UK’s largest trading partner. An exit from the EU is unlikely to change that, but it could add barriers that would increase the cost of trade. Emerging markets, such as China, or the old partner the US, are unlikely to take up the slack. Much is made by ‘Leave’ campaigners about the UK’s trade deficit with the EU — Britain imports a lot more than it exports to the region. However, the UK trade balance with China, whose growing consumer market is held out as a potential alternative to Europe’s slow-growth economies, is proportionally far worse.

Alternative visions

Proponents of an exit from the EU suggest that the UK could adopt the models of several other wealthy, open economies that have been able to thrive on their own

NORWAY

Population: 5.3 million (8% of UK)

GDP per capita: £48,400 (166% of UK)

Norway’s enormous individual and collective wealth and strong social safety nets are built on the proceeds of the country’s oil reserves. Over decades, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund has invested locally and globally for social goals and for profit, which in turn are used as an endowment for its future. Some estimates suggest that the fund owns around 1 per cent of all stocks worldwide.

For the libertarian right wing of British politics, which is largely responsible for the march towards the European exit door, the Norwegian model would be a difficult ideological suppository to take. The oil company is owned by the state, while the government retains major stakes in telecoms, industrial giants and the country’s largest bank. The power utility is state-owned. Government spending on social programmes is high — the public sector accounts for more than half of Norway’s gross domestic product.

The country is a member of the European Economic Area, but that membership is not without its controversy. Opponents complain that Norway is subject to the rules of the EU, but has no stake in negotiating them. The UK would suffer the same challenges, should it decide to leave the union but retain tariff-free access to its markets.

SWITZERLAND

Population: 8.3 million (13% of UK)

GDP per capita: £54,300 (186% of UK)

Switzerland’s financial services sector may feel a little beleaguered in light of overlapping banking secrecy scandals. The country’s vaunted secrecy, and position as a secure place to hold money on the fringes of Europe, has been a controversial topic in Brussels for years. Unlike Norway, Switzerland is not a part of the European Economic Area, although it is a part of the single market and a part of the Schengen agreement on open borders — a concession needed to secure its access to the main bulk of Europe.

The UK is currently not part of Schengen. The Swiss example suggests that signing up to the agreement, or making concessions on open borders, could be a condition of further British participation in the single market – although that is not guaranteed.

Switzerland, like the UK, was seen as a safe haven for financial investors during the eurozone crises. Many people parked their money in the country and bought the Swiss franc as a way of preserving value. You can, however, have too much of a good thing, and the Swiss central bank struggled to keep the currency from appreciating too sharply by printing francs and buying euros, in order to keep the country’s exports — which make up more than 70 per cent of GDP — competitive. This cost them a fortune. In the end, in January 2015, they simply gave up. The currency rocketed upwards, driving some exporters into yet more serious difficulties.

SINGAPORE

Population: 5.6 million (9% of UK)

GDP per capita: £36,600 (125% of UK)

The ‘Little Red Dot’ is a city-state half the size of London, stuck on the end of Malaysia — a country that it was briefly part of in the 1960s. Under its independence leader Lee Kuan Yew, it developed at extraordinary speed to become a modern city, buoyed by its position as a strategic port, strong governance and the rule of law. The financial services industry loves its low-tax environment, and it has become a major international hub for finance — although major banks, including Barclays, have recently pulled out.

High levels of public spending on housing and social programmes mean that standards — and costs — of living are high, particularly for the country’s immediate region, and the crime rate is extraordinarily low. The government’s infamous social order laws, including banning spitting and limiting the importation of chewing gum, are only part of a wide range of public controls and state ownership — opponents say interference — which run deeply through society.

For all of its successes, Singapore is now struggling to maintain its pace of progress. It is heavily dependent on economic growth in its neighbours. When China sneezes, Singapore catches a cold, while the rest of the Association of South East Asian Nations, or ASEAN, view the country with a degree of suspicion, and do not always cooperate. To be a small, isolated and open trading economy on the fringes of a much larger economic bloc, it turns out, does not guarantee sustainable success.

PHOTO: KEYSTONE/GETTY IMAGES

The bottom line

Unbalanced trade