There is little visible police presence in Tegucigalpa’s embassy district, a warren of razor wire patrolled by heavily armed private security and cars with blacked-out windows. This is the safest area of Honduras’ Distrito Central, the sixth most dangerous urban area on earth. For every 100,000 people living here, 73 are murdered each year.

“There are often attacks and threats. Personally, I have had my car sabotaged; I have been subject to surveillance, and wiretapping and attacks on my email. My phone is often targeted, too,” says Dina Meza, a human rights journalist and free speech advocate based in Tegucigalpa. “But I am not afraid.”

Meza, who has been targeted after her investigations into the deadly battles for land rights in the agricultural region of Bajo Aguán, is accompanied by staff from Peace Brigades International, a non-government organisation that provides companions for human rights defenders at risk of attack. She has improved her communications security too, but, she says, she fears for her family. Her daughter, who is also a journalist, almost crashed her car after it was sabotaged. Some threats, Meza says, have boasted of knowing where her son goes to school. Others have been sexual in nature, levied at both her and her daughter.

In 2012, Meza received threatening text messages that promised sexual assault as a consequence for her work covering land conflicts in Bajo Aguán. One message read, “We are going to burn your [pussy] with caustic lime until you scream and then the whole squad will have fun. CAM.”

CAM stands for Commando Álvarez Martínez, a pseudonym that has been routinely used to threaten human rights activists since a coup in 2009 ousted president Manuel Zelaya.

As well as wholesale slaughter committed by narco-trafficking gangs, Honduras is becoming renowned for its oppression of journalists and human rights advocates. This year the country fell five places in Reporters Without Borders’ press freedom index to 137 out of 180 countries worldwide; the group blamed Honduran president Juan Alvarado for giving attacks on journalists a green light by issuing “vicious verbal attacks on the media”.

In March, Honduras was catapulted into the headlines by the murder of indigenous and environmental rights activist Berta Cáceres. Cáceres, who had won the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015 for her campaigning to protect indigenous land, was gunned down in her home in La Esperanza, in western Honduras.

“We were friends, colleagues,” Meza says. “It was five o’clock in the morning when I heard the news, I felt horrible. Berta and I got on very well, and we spoke often about repression [in Honduras]. Sometimes she told me about her fears of protesting and someone being seized or killed in the process.”

Honduran peasants march in Tegucigalpa demanding justice for the murder of indigenous environmentalist Berta Cáceres

The global outcry did not stop the violence. In May, radio journalist Felix Molina miraculously survived two assassination attempts on the same day, taking two bullets in each leg in the process. While there is no way to be sure the attacks were ordered, Molina is a long-time activist for democracy after the 2009 coup.

In early October, Tomás Gómez Membreño, who succeeded Cáceres at the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organisations of Honduras, the NGO she ran, was shot at as he drove home from the office. Shots were fired through the windows and doors of the house of another indigenous leader and environmental activist, Alexander García. Then, Jose Ángel Flores and Silmer Dionicio George, from the Unified Peasant Movement that has been opposing corporate takeovers in Bajo Aguán, were shot dead outside their office in Tacoa.

There are many others. Héctor Martinez, a university professor and trade union leader, was killed in 2015 after denouncing the government. Gladys Lanza was intimidated by unknown people who followed her after she launched an appeal against her 18-month prison sentence for defamation, which she received while defending a woman who had accused a Honduran government official of sexual harassment.

“Our human rights activists are in a defenceless position,” says human rights activist and lawyer Hedme Castro. “We have documented cases of people who have been killed after being persecuted or threatened.”

Official complicity

Many lay the blame for these attacks and assassinations directly at the door of the authorities. For Silvio Carrillo, Cáceres’ nephew, himself a journalist based in the United States, the government was a complicit actor in his aunt’s assassination.

“The government is certainly, absolutely complicit in the murder,” he says. “They may not have been the ones to suggest it — there wasn’t an order from the President to go kill this woman — but they created an atmosphere in which this could happen.

This is a normal way of operating in Honduras. There is a reason why 112 environmental activists have been killed in the five years since the coup. The government is completely complicit in creating that atmosphere.”

Carillo recalls working for an international news network in 2009, watching his aunt as she ducked from hiding place to hiding place. “I asked her ‘how can you keep doing this’,” he says, “and she said ‘well, I don’t have a choice, this is how we live day to day’. People cannot live like this, it’s not right.

“We had always known, and she definitely knew [that she would be murdered]. It was not just a possibility but a probability. Considering the amount of threats that she had received — there are about 40, I think, that were documented — it was almost inevitable.”

The similarities between the deaths of Cáceres and Martinez are blindingly obvious. Both were vocal critics of society in Honduras. Both had been threatened or harassed by unknown men riding unmarked motorbikes, or in unmarked cars. The Honduran government had been charged with protecting both from the fates they were dealt.

The most they can do is finish with our bodies. But the ideas we have, and the legacy we will leave, will still be here, and others are going to take that legacy on

“The fact is that the Honduran government did nothing to try and protect her,” Carrillo says. “They were told that they had to do it, and they failed.”

Amnesty International reports that both “criminal and state actors” have been complicit in acts of aggression and violence against “human rights defenders; indigenous, peasant and Afro-descendant leaders involved in land disputes; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex activists; justice officials and journalists” — an extensive list.

In 2015, the local group C-Libre, a collective of Honduran journalists and human rights commentators, issued 218 alerts over aggressions against free speech. Affecting all manner of human rights defenders, these included — but were not restricted to — the criminalisation of protest; denied access to public information; physical attacks and assassinations. That year, C-Libre reported that 27 activists were assassinated, of which 12 were journalists or public commentators — the highest number since 2010.

There is also, critics say, growing censorship of the media itself, as the government continues to apply more and more pressure to journalists and activists in the country. One source, who did not want to be named, accused the Honduran government of harassing activists and commentators that post regularly on social media sites.

“Every day there is censorship that is affecting the media in Honduras,” says Miriam Grizel, a journalist and activist who works with C-Libre. “If you look closely, there is virtually a favourable political line in every story. We know what is really happening by disseminating social media networks — this is a new form of activism in Honduras — but now they are moving to control that, too.”

man holds a card bearing a picture of Cáceres, which reads ‘The fight continues’

Chilling effect

Celeste González de Bustamante, a professor of journalism at the University of Arizona who studies the impact of violence against reporters, says that the government’s lackadaisical approach to protecting activists has created a culture of impunity. This in turn can have a profound effect on society at large, by preventing the wider public from accessing information that would allow them to hold their governments and public services accountable.

Journalism in Latin America has always been “a venture fraught with risk and violence”, she says. In much of her research, she has found that journalists and activists across the region have to resort to drastic measures just to protect themselves and their families. In Mexico, for example, which is a similarly terrifying location for those seeking to exercise free speech, journalists often attend crime scenes in balaclavas, use radios instead of mobile phones and drive unmarked cars to avoid being identified.

“When you look at Honduras, it is truly an amazing case,” González de Bustamante says. “When you look at the numbers of journalists who have been killed compared to the number of people in the country, it’s pretty staggering. I guess that’s what really needs to be made visible outside of Honduras and outside of Latin America.”

She adds that these are not new issues, but have been a feature of regimes across the region for decades. In Honduras, however, activists and journalists say that things have only got worse since the 2009 coup. Corporate interests — in particular those in the extractive industries, which routinely come into dispute with indigenous communities over land rights — have gained in power and influence as the government looks for economic growth to give it legitimacy.

For those in the firing line, the galling fact is that crimes against them are likely to go unpunished. “The government say they are investigating the deaths of these media workers, but we have seen no results,” Meza says. “When we ask the prosecutor for information, they tell us they cannot give us any because it would damage the investigation. No one knows what investigations they are actually doing, so that fosters impunity and closes the space for society to know what the prosecution is doing.”

Meza has had near misses, but she says she will not back down. Once a child with aspirations of being a doctor, she is now wholeheartedly focused on Pasos de Animal Grande, the website she edits with a small team in Tegucigalpa.

“The most they can do is finish with our bodies,” she says defiantly. “But the ideas we have, and the legacy we will leave, will still be here, and others are going to take that legacy on.”

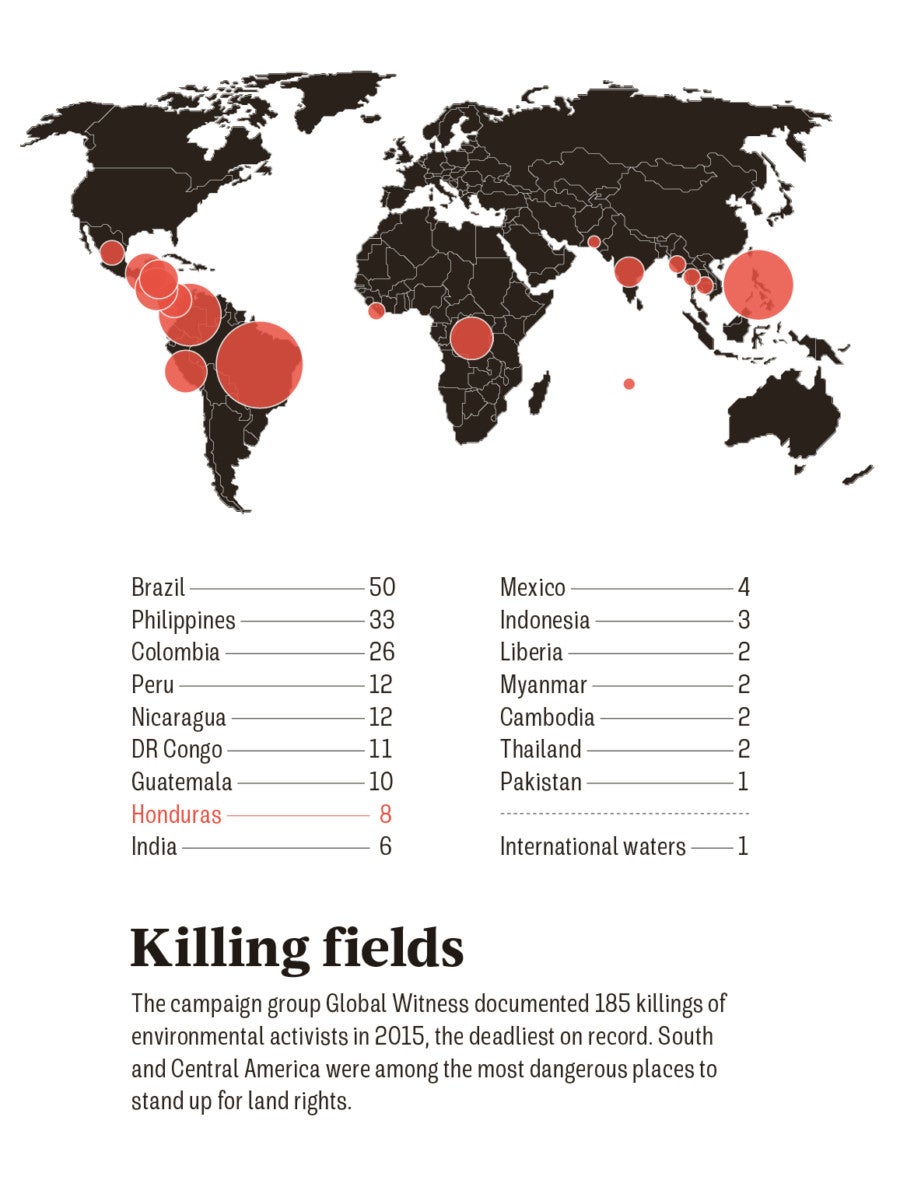

Tracking killings across the world

Official complicity