Bitcoin is still something of a pariah among currencies, but in the not too distant future one of its successors could become a state-backed currency.

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, has outlined probable scenarios where a cryptocurrency could replace the dollar as the preferred alternative currency for countries whose own currency is too unstable.

Such seismic shifts may lead some to wonder when did anti-establishment cryptocurrencies make it into the mainstream? Which nations are leading the charge? And why are some governments still at odds over the issue?

The first thing to acknowledge about cryptocurrencies is that they are not currencies in any precedented sense of the term, explains Garrick Hileman, author of the first study to benchmark their use empirically, published by the University of Cambridge.

Instead, chimera-like, they are part-currency, part-asset and part-application, and as such could evolve in ways that are unanticipated. “If you look at the whole ecosystem that is being developed around bitcoin and ethereum, the thousands of networks and platforms, and decentralised applications, they have more in common with the apps on our phones than they have with the pound,” says Dr Hileman.

The second is that while cryptocurrencies are tolerated with suspicion by most governments – understandably, given their association with tax evasion, money laundering, fraud and crime – they cannot afford to quash them. This is especially true of Western economies which urgently seek growth. For them, the huge amount of innovation and entrepreneurship surrounding cryptocurrencies could prove economically advantageous. “Any dynamic innovative sector, and this is certainly one, is a potential asset to policymakers,” says Dr Hileman.

At the same time, cryptocurrencies possess features that are compelling to central bankers. They provide solutions to some of the logistical and technical problems anticipated from the move to a cashless society, namely around security and the ability to trace payments or the ability to protect privacy, depending on which side of the privacy fence you sit on.

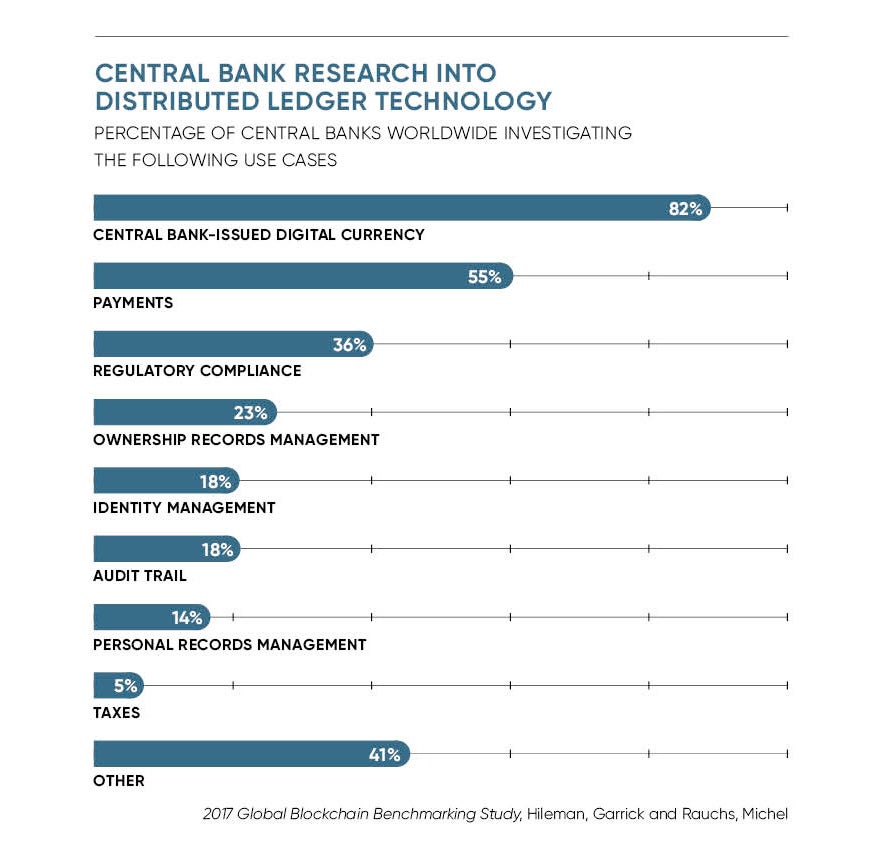

They could also provide central bankers with a means to modernise their payment systems, which for the most part are based on obsolete programming languages and outdated database designs. According to Dr Hileman, almost 60 per cent of central banks are experimenting with ethereum technology, the second largest cryptocurrency platform after bitcoin.

Most of all, there is a real worry that central banks will be “Amazoned” by non-bank rivals, according to Huw van Steenis, global head of strategy at asset-management company Schroders. Issuing currencies is a lucrative business for central banks; what if they lost control of payments should bitcoin take off? Central banks also fear losing their ability to monitor the payment system.

“Given the global fight against terrorism and organised crime, this concern is acute. In an extreme scenario, central banks fear they may even lose control of the money supply,” says Mr van Steenis. For nation states, these concerns make the prospect of taking cryptocurrencies into their own hands more appealing.

So a tentative, loosely regulated race has commenced to stay ahead of the adoption curve. One country’s loss could be another’s gain. “If you ban ethereum then a lot of these solidity programmers [the programming language used for writing smart contracts] who understand how to build applications and run ethereum blockchains are probably going to vacate to somewhere else,” Mr van Steenis adds.

The huge amount of innovation and entrepreneurship surrounding cryptocurrencies could prove economically advantageous

The People’s Bank of China, which is widely believed to be developing its own cryptocurrency as part of its ambition to launch a digital state currency, is keenly aware of these issues. Its decision to prohibit the trading of cryptocurrencies and its ban of the controversial means of cryptocurrency crowdfunding, known as initial coin offerings, could be a direct response.

The country’s core areas of cryptocurrency activity in mining and investment remain unharmed. According to Dr Hileman: “This means they are looking for ways to manage the space and maintain the advantages of being one of the great centres of blockchain.”

Just this month Russia also announced plans to issue a state-backed cryptocurrency, the cryptoruble. Details are scarce, but according to local media the cryptoruble is conceived as a means to stimulate the online economy without having to rely on foreign money markets or third-party brokers, while also allowing the government a way to regulate and track it.

The cryptoruble will be government-issued like an ordinary currency and not mined like bitcoin. Russia’s guiding motivation, according to minister of communications Nikolay Nikiforov, is that if they didn’t do it, European authorities would beat them to it.

Rehabilitation of cryptocurrencies is being aided by the emergence of new software such as chainalysis, which polices and traces criminal behaviour on the blockchain. “The more crime that is committed on the blockchain, vis-a-vis cash, the better because once you have a criminal’s computer and their ‘wallet software’, you essentially have their books,” says Dr Hileman. “You don’t get that with a cash criminal nor do you necessarily have a way to get the funds back.”

This transparency issue is the very reason why state-backed cryptocurrencies are so appealing to states such as China and Russia. But equally it renders them unappealing to countries that favour privacy-oriented banking, such as Switzerland, and to a lesser extent the United States.

Indeed, in recognition of the need to protect privacy-oriented central banking, the Bank of International Settlements has called for cryptocurrency technology to preserve some of the privacy-oriented aspects of cash. For them, and ironically people who have reasons to hide, the technology behind evermore private cryptocurrencies, such as monero and zcash, may prove appealing.

With law enforcement issues and securities regulation beginning to be addressed, the next great regulation debate among officials could be around tax. Arguably, as soon as a non-state cryptocurrency is taxed it has been given the tacit seal of approval and there are distinct transparency advantages to policing tax evasion on the blockchain.

As Kenneth Rogoff, Harvard economist and chess grandmaster, concludes: “The long history of currency tells us that what the private sector innovates, the state eventually regulates and appropriates – and there is no reason to expect virtual currencies to avoid a similar fate.”