The war, rising energy costs, labour shortages, a cost-of-living squeeze, supply chain disruption…the list of crises that businesses face grows by the day. And then, of course, there’s that planet-sized elephant in the room: climate change. But what if there was a way for the c-suite to deliver better economic and environmental performance while also improving organisational resilience to world events?

In fact, there is: the circular economy. It involves moving away from a linear ‘take, make and dispose’ model and toward a ‘reduce, reuse, repair and recycle’ one that keeps existing resources in use for as long as possible. For businesses, it offers a path to a more sustainable future; and crucially one that is financially sound and resilient to disruption.

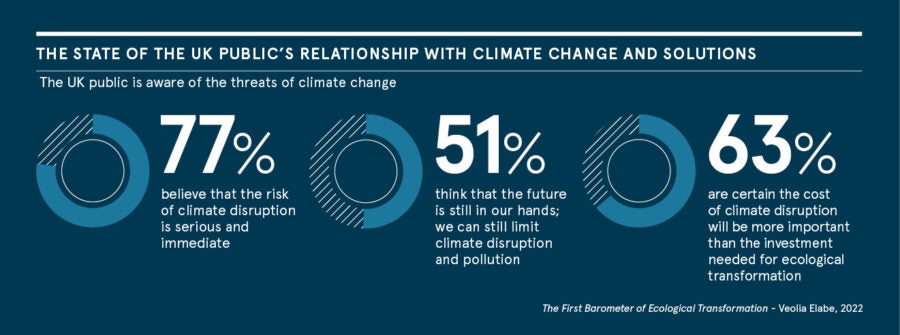

Firms that take the first steps along this path are likely to be rewarded by the public. A recent survey by the leading resource management company, Veolia revealed that while 77% of people in the UK think the risk of climate disruption is serious and immediate, only 11% think it’s too late to change course. For business, over 80% of respondents also said they would buy everyday products packaged in or made from recycled content.

“The behaviour of consumers is very important for businesses, and over the last few years we’ve seen a big increase in pledges to change and adapt – to improve the eco-design of packaging, for example,” says Tim Duret, director of sustainable technology at Veolia UK, which champions ecological transformation. “Obviously it can have a cost (but not always) for industries, but over the long term it will provide savings.”

The shift to circular practices is essential for both businesses and the environment. “The public are increasingly conscious of their impact and are ready to embrace the environmental solutions needed” says Gavin Graveson, senior executive vice-president, Northern Europe zone, at Veolia. “It’s now up to businesses and governments to push faster towards ecological transformation because we can’t rely on fossil fuels or virgin materials. The time is now, we need to invest in resilience because we can’t afford – both financially and environmentally – to do nothing.”

Cross-industry impact

As practically every industry produces a waste stream, the shift to a circular economy could have a deep and wide-ranging impact. In the petrochemical industry, for instance, sulphuric acid – one of the most widely used chemicals in the world – can be regenerated to give it a second life. Valuable solvent components can also be extracted from mixed waste streams, sent for solvent recovery and reused, thereby reducing both the need for virgin solvent and the financial impact of purchasing raw materials.

We can’t rely on fossil fuels or virgin materials. The time is now, we need to invest in resilience because we can’t afford to do nothing

Wastewater is also a potential source of energy, biosolids and other resources such as nutrients. This, as the World Bank says: “Represents an economic and financial benefit that contributes to the sustainability of water supply and sanitation systems and the water utilities operating them.” And while recycling and remanufacturing are already practised in the automotive industry, car manufacturers are now launching dedicated circular economy initiatives to generate higher revenues and reduce material sourcing costs.

Electric vehicle (EV) battery circularity is of increasing importance too. An anticipated 350,000 tonnes of end-of-life EV batteries are predicted to be in the UK by 2040 – a source of vast amounts of valuable resources like lithium, nickel, copper and cobalt.

Veolia’s recently announced electric vehicle battery recycling facility in the West Midlands will have the capacity to process 20% of the UK’s end-of-life electric vehicle batteries by 2024. “As the demand for electric vehicles increases, we will need this facility to ensure we don’t hit a resource crisis in the next decade,” says Graveson.

The plant will discharge and dismantle batteries before the mechanical and chemical separation recycling processes are completed, enabling the valuable minerals they contain to be reused.

“When we go from a linear economy to a circular economy, one of the things we are doing is increasing our resilience,” says Duret. “Batteries, for example, require lithium – and we have minute levels of lithium in the ground in the UK.”

Recovering lithium and metals such as copper and aluminium from EV batteries – a process known as ‘urban mining’ – could also cut greenhouse gas emissions from battery production by 50%. As an estimated 500,000 gallons of water are required to extract one tonne of lithium using traditional mining processes, it will also drastically reduce water consumption.

Securing supply chains

Critical mineral scarcity could impact everything from mobile phones to televisions and medical devices. Today’s supplies are predominantly overseas, meaning UK industry is highly vulnerable to market shocks, geopolitical events and supply chain disruptions. The fact that these minerals are also an essential component of wind turbines means they are also vital for boosting renewables and improving the UK’s energy security.

“Again, it’s about providing the recycled materials from the UK to manufacture new products without having to import raw material from around the globe.” says Duret. “It provides a greener economy but also a more stable economy, because when the source of the material is within the UK, then we don’t have to worry about transportation, and we don’t have to worry about geopolitical disruption abroad. So, it’s good for the planet, and it’s good for the economy too.”

Food waste is another potential source of domestic energy, as it can be used for the production of biogas. But the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs’ Environment Act, which will make it a legal requirement in England for companies to recycle food waste, should start to tip the balance toward an even more circular model.

“It will help companies like Veolia to collect more [food] waste and transform it into either organic fertiliser for the farmers or compost for the general public, but also energy [in the form of biogas],” Duret says.

Can the circular economy really deliver better economic and environmental performance while also improving organisational resilience to world events? “One hundred percent,” says Duret. “It’s a win for the environment, for businesses and for society.”

For more, please visit www.veolia.co.uk/raconteur

The war, rising energy costs, labour shortages, a cost-of-living squeeze, supply chain disruption…the list of crises that businesses face grows by the day. And then, of course, there’s that planet-sized elephant in the room: climate change. But what if there was a way for the c-suite to deliver better economic and environmental performance while also improving organisational resilience to world events?

In fact, there is: the circular economy. It involves moving away from a linear ‘take, make and dispose’ model and toward a ‘reduce, reuse, repair and recycle’ one that keeps existing resources in use for as long as possible. For businesses, it offers a path to a more sustainable future; and crucially one that is financially sound and resilient to disruption.

Firms that take the first steps along this path are likely to be rewarded by the public. A recent survey by the leading resource management company, Veolia revealed that while 77% of people in the UK think the risk of climate disruption is serious and immediate, only 11% think it's too late to change course. For business, over 80% of respondents also said they would buy everyday products packaged in or made from recycled content.