It’s not surprising that the UK is moving away from cash. The first recorded paper-money transaction took place in 7th-century China and, although banknotes were not issued here until the Bank of England was founded in 1694, cash is nevertheless starting to feel a bit old hat.

Cash transactions are almost quaintly anachronistic. The paper itself has only nominal intrinsic value, of course, and it serves as a “proof” that the carrier has wealth totalling the number written on its face.

To this day, every note carries a “promise to pay the bearer” made by the bank, meaning theoretically any of us could turn up in Threadneedle Street tomorrow and ask a clerk to swap a £20 note for a tiny ingot of gold. When you pay someone in cash, you essentially concede to them this proof of wealth, rather than wealth itself. How odd.

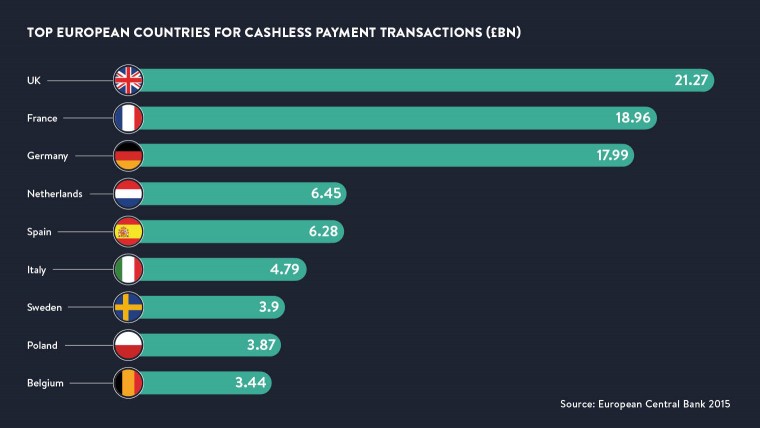

To see the full infographic click here

Granted, cash has an allure that is timeless. A suitcase stacked neatly with rows of high-denomination notes makes for a better movie scene than someone shiftily handing over a debit card. It’s nice to see the big numbers, feel the crispness of treated paper and marvel at the intricate designs, but there is little else to recommend it compared with a tidal wave of new and sophisticated channels.

Electronic payments are less tangible, but more convenient and, in a world where everything happens in an instant, convenience is king

Electronic payments are less tangible, but more convenient and, in a world where everything happens in an instant, convenience is king. The move to new payments was evidenced last May when, according to the UK Payments Council, the value of card transactions overtook cash for the first time.

Global discrepancies in the payment landscape

In this country, at least for those with a comprehensive view, the appetite for new ways to pay is vivacious. Contactless, online, mobile, e-wallets, apps, bitcoin, you name it, we’re buying with it. And yet it’s not the same story globally. The world is going digital, but not all at once.

The varied picture from country to country is painted with a number of factors – cultural, infrastructural, demographic and so on. But the differences are not straightforward; it’s not as if the biggest economies lead the pack and developing ones bring up the rear.

“Many developing countries have the ability to leapfrog and adopt cashless payment systems to improve their trade,” says Jerry Norton, vice president of financial services at CGI. “Countries in Africa have adopted mobile payment systems, such as M-Pesa, which in some respects are more sophisticated than those available in Europe and North America.”

Across the developing world, technology is seen not just as a conduit for faster payments, but also a bulwark against fraud.

Chris Dutta, director of Piccadilly Group, says: “In emerging countries, traditional payment mechanisms have often been subject to crime. The growth in technology has allowed citizens and businesses to overcome this, which is reflected in the take-up rates of cashless payments.

“In Africa, for example, a quarter of people who have a mobile phone have a mobile wallet. Conversely in many countries in Western Europe, the reliability of cash-based transactions means citizens have been happy to rely on these.”

Japan still favours cash

Meanwhile in Japan, where technological opportunities are usually seized upon with gusto, cash is still favoured by the majority of people. A new study by MasterCard revealed that 85 per cent of payments in Japan were made with cash, compared with 48 per cent in the UK.

Separate research by the Bank of Japan showed that Japanese consumers see convenience as the main benefit of e-payments, while in the UK we also like safety, time-saving, the ability to pay online and better anti-fraud features.

Incidentally, this is good news for British-based retailers, according to Jo Allison, a behavioural analyst at Canvas8. She points to a Dun & Bradstreet study showing that people spend between 12 and 18 per cent more when they use credit cards over cash. “The method of payment has a sizable impact not just on how consumers spend, but how much they spend,” she says.

More good news is that the UK is well placed to convert. Mr Norton adds: “The UK, Australia and Canada have a strong history and knowledge of electronic payment infrastructure and innovations. Because they were early adopters of electronic payments and innovations like ATMs and chip and PIN, they have a strong foundation on which to invest in and modernise.

“Elsewhere cultural and demographic differences, and maybe a lack of a credit economy, mean card payments have discriminated against and thus consumers remain accustomed to using cash.”

Germany remains skeptical

This explains why two near neighbours such as Germany and Sweden can have such wildly different adoption rates. Germany, the engine room of the European Union and the world’s fourth largest economy, should be positively buzzing with electronic payments, but it isn’t, not at all.

Around 80 per cent of transactions in Germany are still made by exchanging sweaty clods of ex-tree. Broadly speaking, the Germans are sceptical about making card payments – second nature in the UK – let alone anything more virtual or cutting edge.

Ron Delnevo, executive director at the ATM Industry Association, says Germanic thriftiness and love of privacy could be the two main drags on e-payment pick-up.

“Culturally, Germans are extremely reluctant to have any intrusions on their privacy,” he explains. “Using cash eliminates the risk of banks or governments tracing when and where you purchase something, how much it costs and even what it was.

“The historical scars of hyperinflation have also influenced the German mindset. In addition, using cash means customers will only be able to spend the money in their pocket. Germany is a nation known for priding itself on its thriftiness, avoiding debt and shunning credit cards. That the German word for debt is the same as for guilt – schuld – is telling.”

Now there’s no suggestion here that Swedes are debt-hungry spendthrifts, but their attitude is very different. So keen are they on electronic payments that the government has created policies to discourage transactions using banknotes.

It may have to reverse these thanks to their alarming effectiveness. Cash circulation has plummeted since a high-point in 2007. Back then the average value of paper in circulation was just over 100 billion krona (£8.69 billion). In February Sweden’s Riksbank said the figure had fallen to SEK62 billion (£5.39 billion), a drop of around 40 per cent.

It’s no surprise then that when it comes to innovation in this area, Scandinavian countries are blazing a trail, according to Andrew Neeson, market intelligence manager at VocaLink. Here, pressure to update comes directly from the government and the financial system itself.

“Finland has the highest amount of non-cash transactions in the world, per head, and Norway is also very high. Scandinavian countries are early adopters of innovations, such as internet banking,” he says.

Yet regional variations have created a patchwork of non-cash payment systems across Europe, says Myles Dawson, country manager for Adyen UK. The payments industry here is yet to condense into a handful of winners in the same way that, say, smartphones have.

“In Northern European markets, shoppers prefer debit-based payment methods, such as SEPA [Single Euro Payments Area] Direct Debit, which is particularly strong in Germany, or iDEAL, popular in the Netherlands, or open invoice payment methods in Scandinavian markets,” he says.

It won’t come as a shock to learn that further afield the payment landscape is different again; not just consumer preferences, but the very technology that’s on offer. “China is a hotbed of innovation when it comes to mobile payments, but the methods people use to pay are completely different to the UK,” says Mr Dawson.

“Two e-wallets – Alipay and WeChat Pay – lead the way. With hundreds of millions of users, they are essential for UK businesses to offer in order to reach the critical mass of potential shoppers in the Chinese market.”

Cash is not dead yet

Are we witnessing cash’s last hurrah? Not quite. In fact, globally its use is increasing, not declining, because of the net effect of fast economic growth in developing countries. Cash withdrawals in China increased 64 per cent between 2010 and 2014, growth mirrored in the other BRIC territories, Brazil Russia and India.

Even Sweden, a bellwether in e-payments, has put the brakes on its cavalier romp into a cashless society for fear of literally running out of money.

But the endgame sequence has been initiated and in the next decade, momentum, especially in developed countries, will continue to shift away from fivers and tenners. Soon, then, ransom movies will lose one of their most iconic scenes, but the film industry’s loss will be the global economy’s gain.

CASE STUDY: KENYA PLAYS LEAPFROG

Africa is not usually noted for its global technological leadership, but large swathes of the continent are adopting mobile payments faster than developed economies in Europe, Asia and the Americas.

Jordan McKee, senior analyst of mobile payments at 451 Research, points to high rates of smartphone ownership as one reason for this apparently counter-intuitive trend. “Much of Africa, and specifically countries like Kenya, are leaders in the transition away from paper currency,” he says.

“Here, the migration to mobile has been underway for some time, with initiatives such as M-Pesa essentially leapfrogging the use of debit and credit cards. Mobile serves as a vastly superior and sensible payment vehicle to existing alternatives.”

M-Pesa was introduced in Kenya in 2007 and two years later it already had nine million customers or 40 per cent of the adult population, according to the World Bank. By 2013, this figure had risen to two-thirds and a quarter of the country’s GDP flowed through the system.

It permits institutional transactions, allowing companies to pay salaries and collect bill payments, making it a convenient way to transfer money. Until very recently, before the sweeping growth of Uber, paying via a mobile phone for simple services such as a taxi journey was easier in Nairobi than it was in London, the financial capital of Europe.

“Mobile negates the need to spend upwards of a day travelling to pay a bill with cash – a reality across much of sub-Saharan Africa,” adds Mr McKee.

“The unfortunate reality across many developing economies is that banks are not accessible. Mobile phones, however, are. As such, there are literally over 100 initiatives globally intended to pull the financially underserved into the confines of the digital payments ecosystem via their mobile devices.”

Global discrepancies in the payment landscape