Computer-based personality and competency tests are increasingly used as a method of recruitment, but how accurate can these tests be? Is it possible for a computer to analyse how individuals will fit into a company?

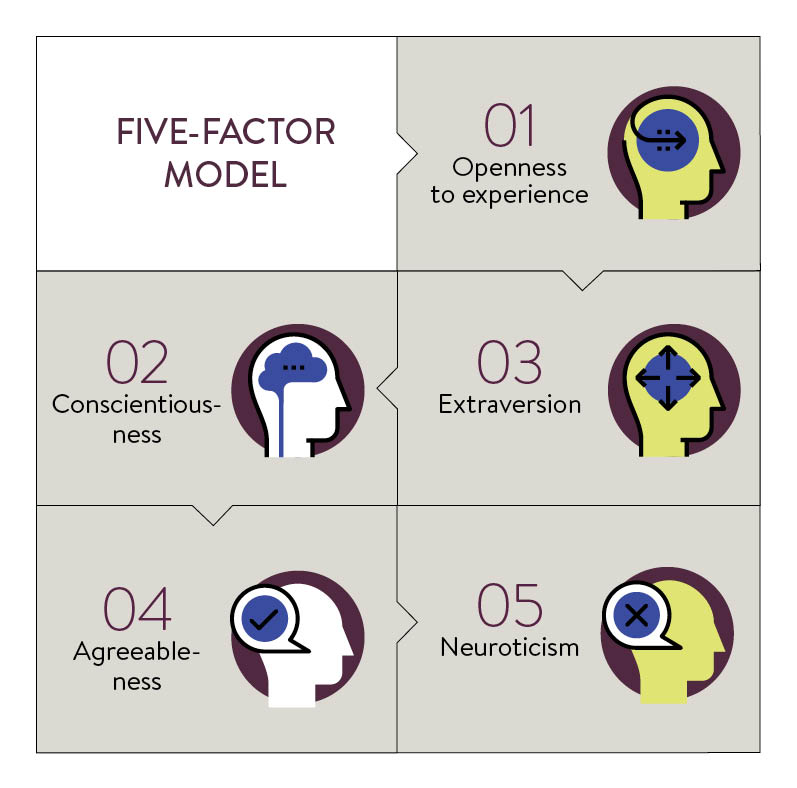

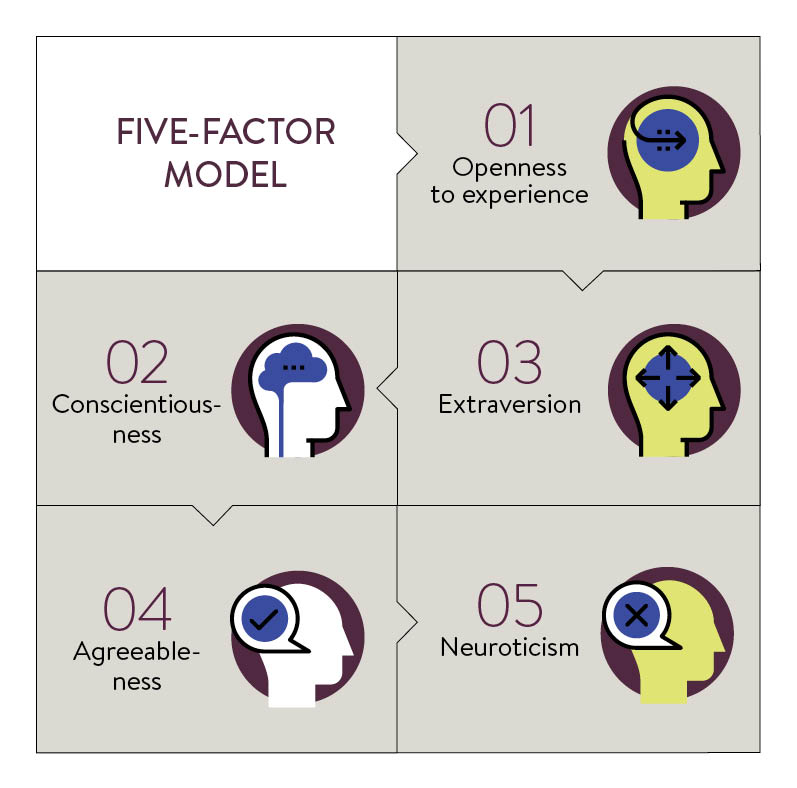

We’re all familiar with the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator, which works on the assumption of four principal psychological functions by which humans experience the world – sensation, intuition, feeling and thinking, and its forerunner, the Five-Factor Model, which focuses on five key personality traits.

But the business world is increasingly moving towards a computerised approach. “In the last two years, more data has been generated than in the rest of the world’s entire history. Naturally this has had a massive impact on human ability to produce and apply robust insights to improve a company’s performance across almost all industries and sectors, not least HR,” says Tom Marsden, chief executive of hiring analytics company Saberr.

Researchers think artificial intelligence has the capacity to gain a better insight into our personality than close companions, not to mention potential bosses

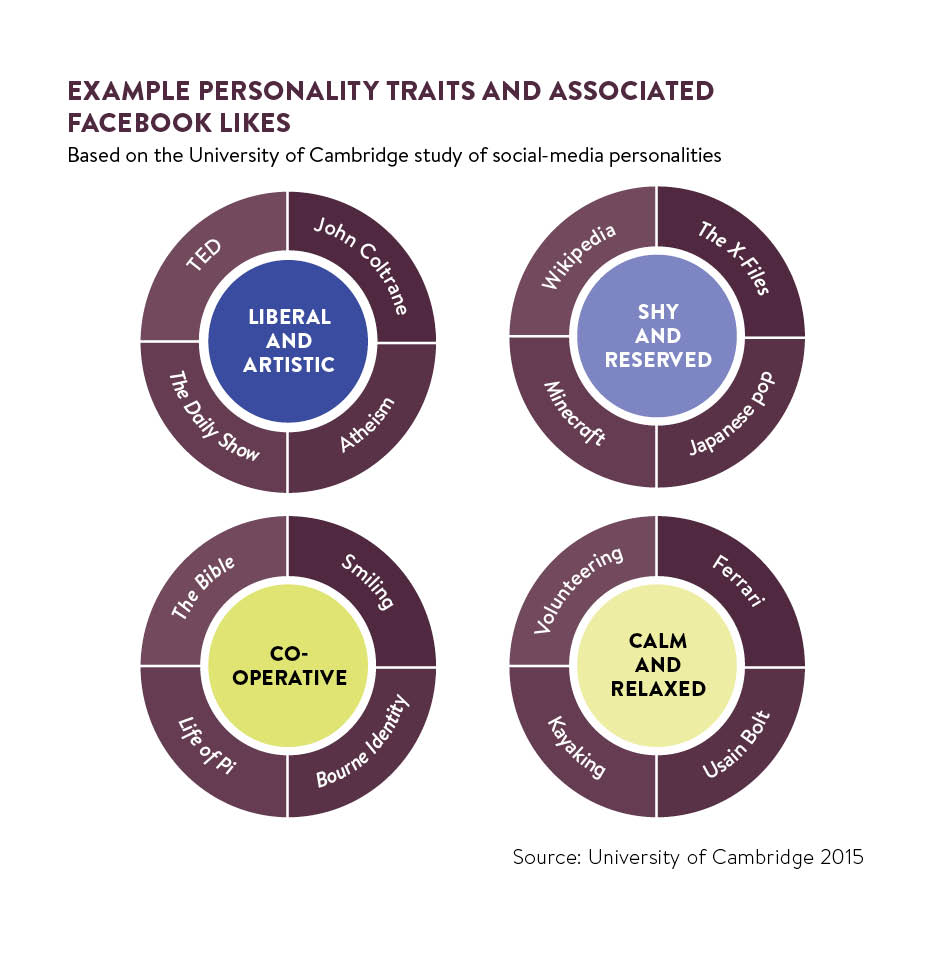

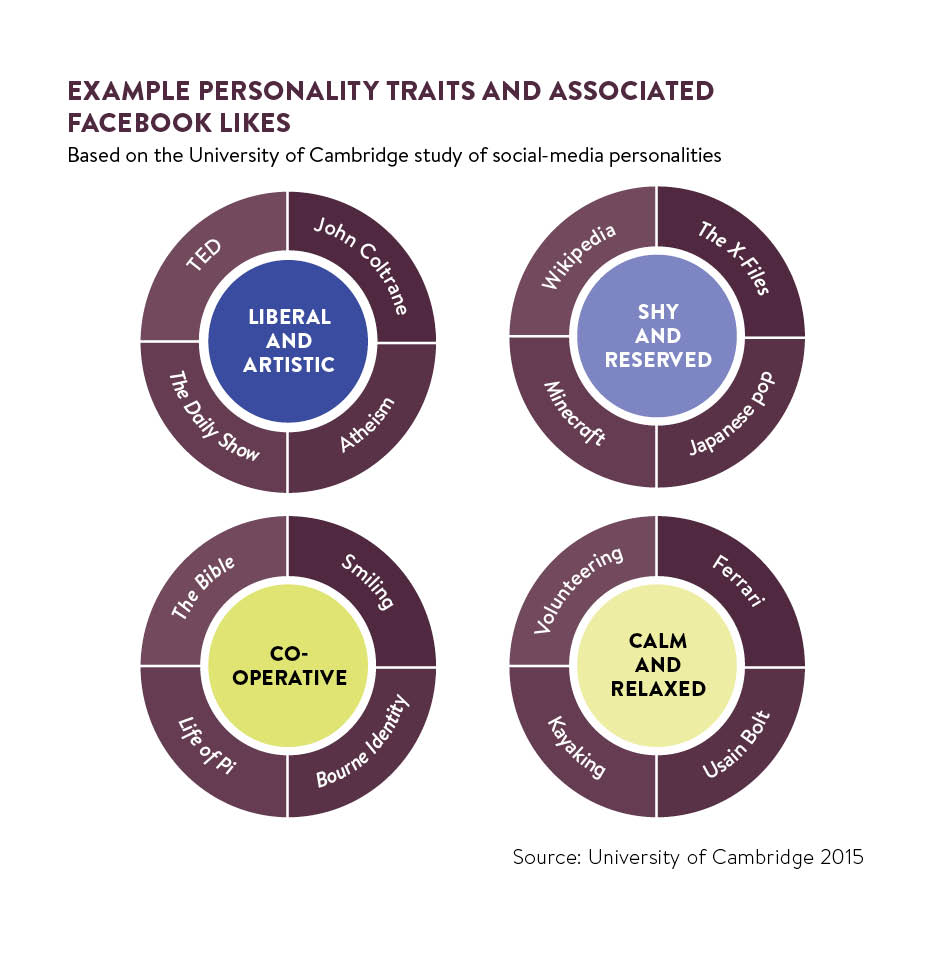

These insights can be impressive. In a University of Cambridge study last year, researchers found that a computer could more accurately predict a person’s personality than a work colleague by analysing just ten Facebook likes. The researchers think this sort of artificial intelligence (AI) has the capacity to gain a better insight into our personality than close companions, not to mention potential bosses.

“At the moment, analysis of your average social media user can predict personality type to approximately 75 per cent accuracy but, though it’s getting closer, someone’s social footprint, for example, is not as accurate as an online test for understanding personality,” says Mr Marsden.

Matt Roberts, chief executive of the Directors Online Network, is a big fan of psychometric testing. “We’ve used it for years and, although it doesn’t tell you someone is going to be perfect for a job, it tells you if they’ll be wrong for it, and where you’re likely to get the most out of them,” he says. “We look at someone who’s doing a job well and try to understand their profile, then recruit similar people.

“It works for some roles better than others, but I’ve only gone against the profile for sales staff twice – and regretted it both times.”

The changing recruitment process

There is a school of thought that says algorithms will replace humans across a significant portion of the recruitment process in the future.

Mr Marsden says: “The role of the recruiter is likely to become more strategic to understand the basis of the algorithm, to check for bias and to review results. This isn’t to say there is no future for the human element of recruitment, it’s just that much like other industries, accounting for example, it will evolve. It’s therefore increasingly important for organisations to frequently reflect upon how computer-generated analytics can strengthen their existing HR strategies.”

As such, it should be treated as “another voice in the room” when making a decision about a person’s career. “But human judgment is required to understand how to combine that insight with other available perspectives and make a decision,” he says.

Charles Hipps, chief executive and founder of recruitment tech company WCN, says: “There are now thousands of data points available that can help with profiling an applicant by keeping them engaged and enabling them to make decisions. Picked with job descriptions in mind, the examination of results can be analysed in more evolved ways than traditional psychometric tests.”

The key to doing this well, says Mr Hipps, “is to focus on gathering high-quality intelligence and to become smarter and more immersive”. To this end, more and more firms are utilising multimedia techniques, such as video interviews and gamification. “This helps to maintain momentum with candidates, allowing employers to sell brand values and letting candidates determine if they are a good fit for them and vice versa,” he says.

AI is unlikely to ever be able to predict fully how a team of people can or will work together. “People also change over time,” says Mr Marsden, “which is the wonderful thing about being human.” However, we also know that we don’t change radically or regularly. Even much of our irrational behaviour is consistent, and we are also hugely influenced by our social group and surroundings. “AI can already help us understand ourselves better, especially in the context of the people we work with and our work surroundings,” says Mr Marsden.

Hiring for ‘culture fit’

There is a growing trend of organisations adopting the approach of hiring for “culture fit” and then training people to be successful in their roles.

Youyou Wu, a researcher on the University of Cambridge project, believes it’s possible to use a computerised approach to company culture. “Companies could choose to characterise their current top performers for each job category and find candidates with a similar personality,” she says. “They could also study existing teams to see what personality compositions tend to optimise the team dynamic and efficiency, and recruit and group potential employees accordingly.”

David D’Souza, the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development’s London head, is sceptical. “The claims around the accuracy of computer-based personality tests vary significantly and market forces, understandably, drive a lot of the claims,” he says.

“While most companies have their own ‘values’ that they put in the annual report, in reality the lived values of the organisation are normally very different. Understanding how people might fit in with the complexity of sub-cultures within an organisation, each with their own politics and social norms, is far harder than matching people to how the organisation might like to see itself.”

Also most tests contain a margin of error that would surprise the people undergoing them. “Their usage as a supporting data point in a key hiring decision makes sense, but basing decisions on them alone would not be best practice,” says Mr D’Souza.

“If you like the candidate, then you are likely to ignore or dismiss the results of a test saying they are a bad fit. If first impressions were poor, then the result of testing or profiling may well be ignored. From a candidate’s point of view, it can be a very dehumanising experience, realising that the answers you give to a select group of questions will determine your likelihood to be selected for a role.”

The changing recruitment process

Hiring for 'culture fit'