When travel company Thomas Cook collapsed with the loss of 9,000 UK jobs and leaving 150,000 travellers stranded, it was chief executive Peter Fankhauser who faced the cameras and media glare. But while public scrutiny may be on the big boss, behind the scenes of a business restructuring effort, the CFO is a pivotal figure.

The CFO is at the centre of operations during financial difficulties. They will be expected to have a firm grip on the health of the company and provide information at short notice to lenders and the board to enable them to make strategic decisions.

Eric Benedict, managing director at consultancy AlixPartners, says a full-blown business restructuring process can be a whirlwind for CFOs, who are now increasingly pivotal in restructuring for stability and resilience.

“He or she becomes an absolutely central figure in understanding the financial dynamics and flows into and out of the business,” says Mr Benedict, adding that it can be a steep learning curve for CFOs who have not been through the process before. “Unfortunately these days, there are still too many examples of companies that haven’t been through a restructuring and think they can manage it, but aren’t prepared.”

CFO business strategies

Changes in the way companies borrow money have also thrust the CFO into a central position when companies underperform or become distressed.

Jo Windsor, partner specialising in corporate recovery and insolvency at law firm Linklaters, explains that many banks sell on their debt to new lenders, such as distressed debt firms or private lenders. This means when a company is unable to pay its debts or in the midst of a business restructuring, the CFO may suddenly have to deal with dozens of unfamiliar lenders all demanding different information at very short notice.

CFOs become a central figure in understanding the financial dynamics and flows into and out of the business

“It can be quite scary,” says Mr Windsor. “When things are going well they [the finance director] will have a relationship with their bank and it will all be fairly cosy. But they may suddenly find themselves in a new situation where their bank may have sold out and they have a whole new lot of faces at the table they haven’t dealt with before and they haven’t any experience.”

The market for corporate loans that have few investor protections, known as covenants, has blossomed in recent years with record amounts of so-called “cov-lite” debt being issued globally in the past two years. Covenants traditionally act as an early warning sign to investors that a company is in trouble, but the rise in these loans means companies are not required to report their financial performance to lenders as frequently. This can mean a crisis can quickly escalate.

Mr Windsor says: “This is part of the challenge facing the finance director because in a sense people only get interested when the position has become very serious.”

Restructuring plan

On the flip side, the rising number of these loans has meant well-prepared companies have more time to develop CFO business strategies behind closed doors.

Joel Ferguson, partner at law firm Allen & Overy, has seen more companies planning well in advance to avoid business restructuring situations.

“We have a couple of borrowers who won’t have an issue to the external world for another 12 to 18 months, but we are sitting here strategising with them different scenarios and how they might play out over the next 12 months,” he says, adding that this allows his clients “to come pre-baked with solutions” if a problem occurs.

This sort of behind-the-scenes planning to avoid calamitous business restructuring is becoming more common. Blair Nimmo, head of restructuring at KPMG, says he is increasingly having conversations with finance directors of companies that are not distressed, but simply not as profitable as they should be.

“If you go back 20 or 30 years, we were all about being brought in by companies, or more commonly lenders, in a crisis management situation when they were running out of cash,” says Mr Nimmo. “Nowadays about half our people are dealing with companies that are in no way shape or form nearing insolvency, but simply are underperforming.”

3M, the manufacturing conglomerate and maker of Scotch Tape and Post-it Notes, is one such business undergoing a major business restructure. The company saw a drop in sales in 2019, partly due to the ongoing US-China trade war hitting demand from its Chinese customers. In April, the company confirmed it was combining its industrial and safety and graphics businesses in an effort “to drive productivity, reduce costs and increase cash flow”. It also announced 2,000 job cuts worldwide.

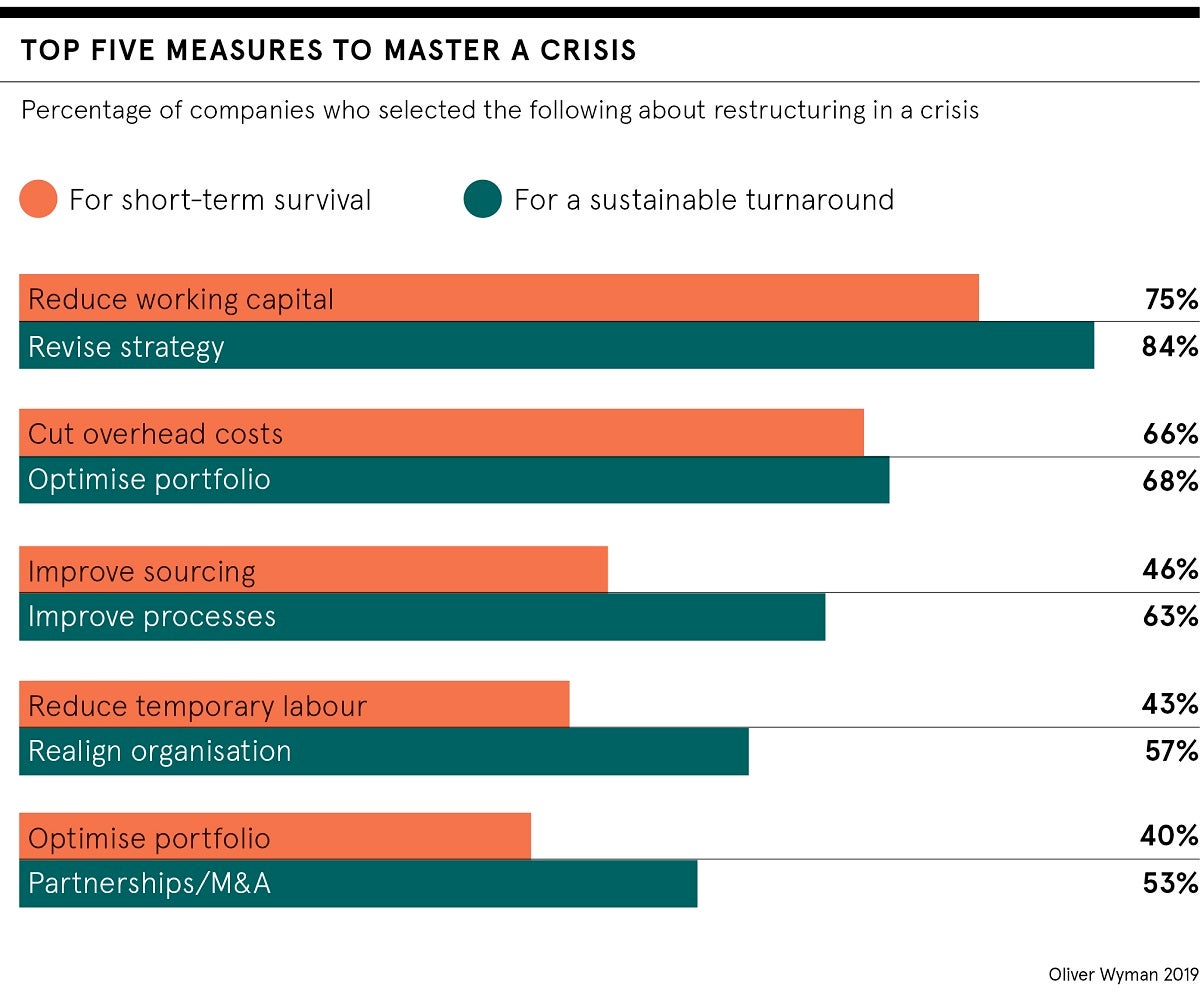

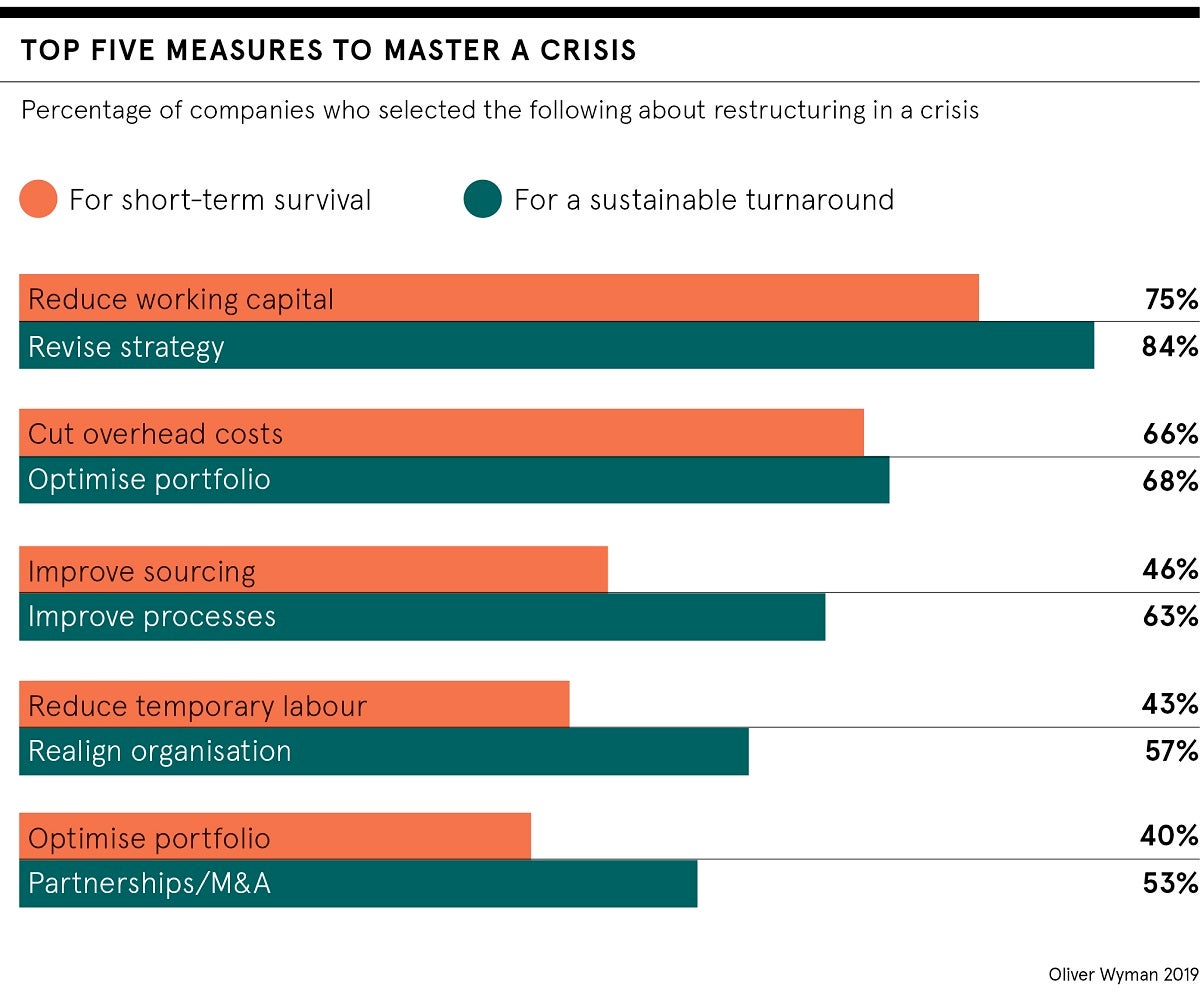

Companies are becoming more aware of the operational changes they need to make to avoid crisis situations. This could involve rejigging supply chains, dealing with working capital, trimming staff numbers, moving headquarters, closing bricks-and-mortar stores or hiving off underperforming departments into new legal entities.

CFO business strategies

Restructuring plan