In recent years the UK’s economic performance has outshone that of other countries, with steady growth in jobs and new businesses. However, one area where the UK is lagging behind other major economies is in its productivity, a key metric of future prosperity.

Given the UK’s otherwise strong economic outlook it is a source of concern and frustration, but there is more to this than meets the eye. Measuring productivity is at best an inexact science and becomes more difficult as the economy becomes more complex.

Comparing levels of output between countries, for example, may not be the most accurate method, while some critics have suggested that too much focus is placed on UK comparisons with the rest of Europe and the United States.

Are different countries even measuring productivity in the same way? According to a report by Close Brothers Group, entitled The Power of Productivity, based on a survey of 1,400 UK, French and German small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), nearly three in ten are not measuring it all, while one in twenty SMEs don’t understand what productivity is.

Given the radical changes in the way that people work, it may be time for a rethink on how we measure UK worker productivity, and how we compare it across regions and international borders.

UK compared worldwide

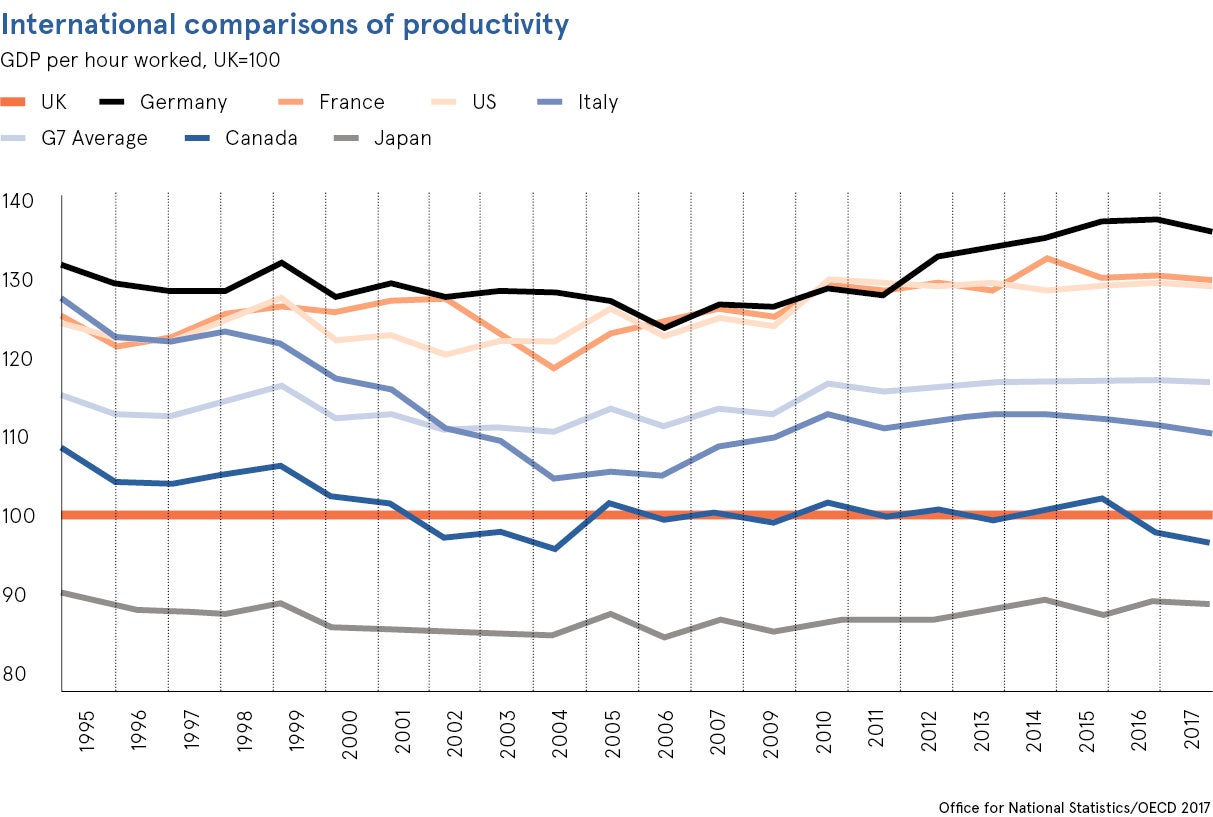

Figures from last October’s Office for National Statistics and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) comparisons of GDP per hour worked between the UK and other global economies were stark. They showed UK productivity as 21.8 per cent lower than that of the US; 22.3 per cent lower than France and 25.6 per cent lower than Germany. UK productivity also trailed the rest of the G7 by 15.1 per cent.

But as Joe Nellis, professor of global economy at Cranfield School of Management, points out, international comparisons are fraught with problems. “These involve differences in the structure of economies, for example, the size of the service sector versus industry, the size of the public sector, educational attainment, working hours’ regulations, the scale of corporate investment, technological investment, infrastructure investment and so on. Comparing productivity across countries is akin to comparing apples with pears,” he says.

Yet this still doesn’t explain why France, where workers take more holidays and put in fewer hours each week than the British, is more productive than the UK.

“Over many years, France has put in place restrictions on the number of hours worked and has much stronger trade unions than in the UK that have successfully defended workers’ pay and conditions of work,” says Professor Nellis. “There is also considerable resistance to redundancies in France. These factors combined have resulted in higher labour employment costs for the business sector. To counteract the higher costs, business has tended to invest more in the latest technology and machinery, thus supporting higher labour productivity compared to the UK.”

The downside to this trend, however, is that employment growth in France has been more limited than in the UK. Unemployment in France has been around 10 per cent over the past decade while in the UK unemployment has fallen to around 4.3 per cent.

“A higher ‘natural rate of unemployment’ is the price that France has had to pay for its higher labour productivity,” adds Professor Nellis. “For comparison, the latest employment rate for the UK is just over 75 per cent, while in France it is only 65 per cent.”

North-south divide

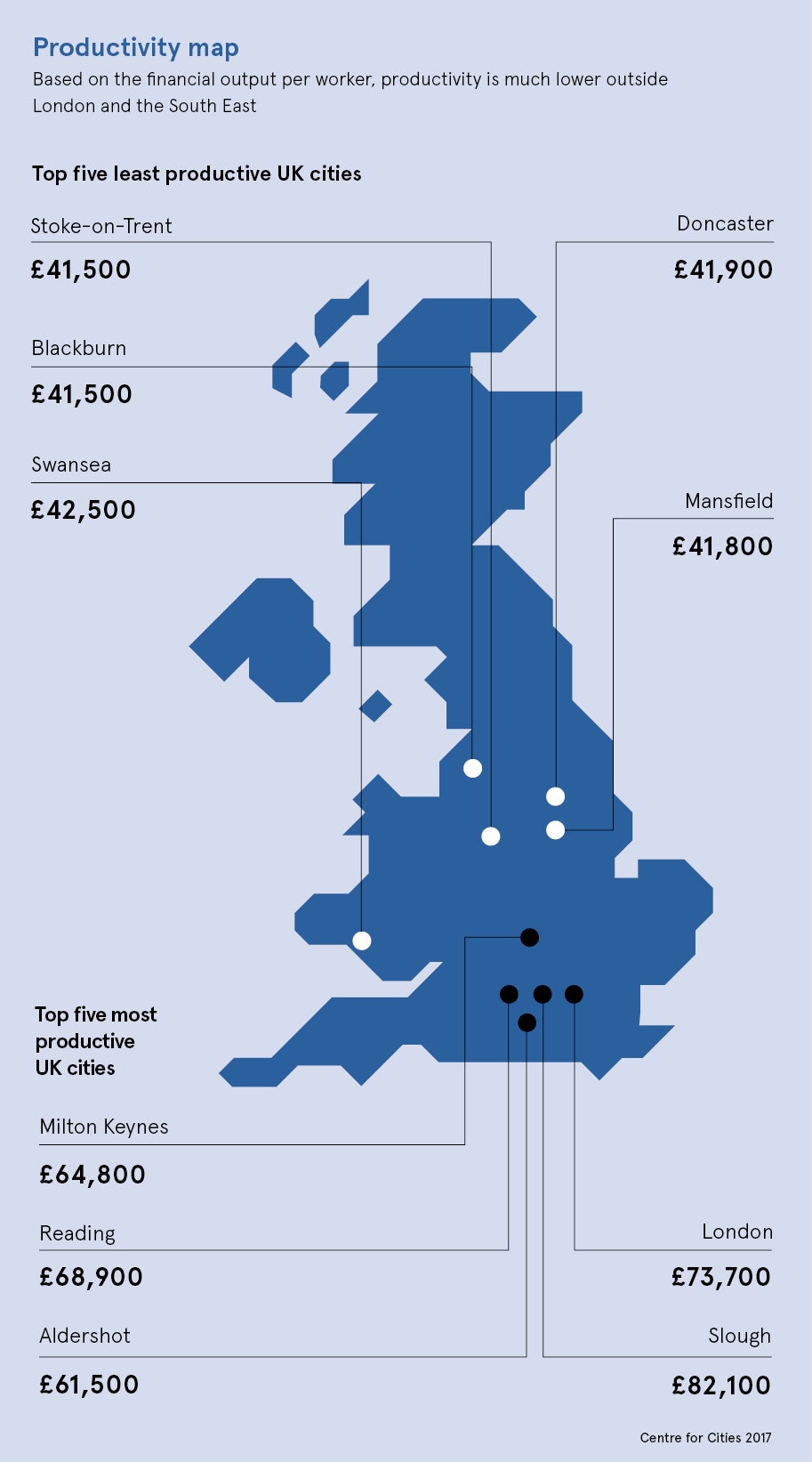

Within the UK, drivers of productivity vary between regions and therefore contribute to the productivity gap that exists between the north and south. A key finding in a report published by think-tank Centre for Cities was that the UK’s top five most productive cities are based in the South East while the five poorest performers are located in the Midlands, North West and Wales.

Factors such as effective transport links and quality digital infrastructure, as well as good secondary education and employees’ basic skills, and businesses’ managerial quality all have significant influence on productivity performance, explains Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK.

“Businesses in London, for example, are on average more export-oriented than the rest of the UK, which facilitates their access to best practice. The capital also has the best transport links, and is a leader in innovation, alongside the South East and the East of England,” she says.

“Northern regions and the Midlands perform relatively worse on innovation and educational attainment than the South East and London. Moreover, businesses in the North express a relatively higher degree of dissatisfaction with the local transport infrastructure, crucial for ease of access to the best workers and managers.”

The geographical spread of industry sectors could also be a contributing factor. While London has a large share of financial, information and communication services in its regional economy, all requiring high-skilled and relatively more productive workers, areas with poorer average productivity performance, such as Wales and the North East, have a relatively high share of public sector activities, which tend to be less productive.

“If the UK is to improve its productivity performance to match that of its Western peers, every region nationwide needs to play its part in addressing weaknesses where they exist and boosting the region’s existing strengths,” says Ms Selfin. “Initiatives should include developing a fit-for-purpose local infrastructure, encouraging innovation and the adoption of best management practices, and promoting a higher level of skills and education in the local workforce, starting at the earliest possible age.”

Working hours

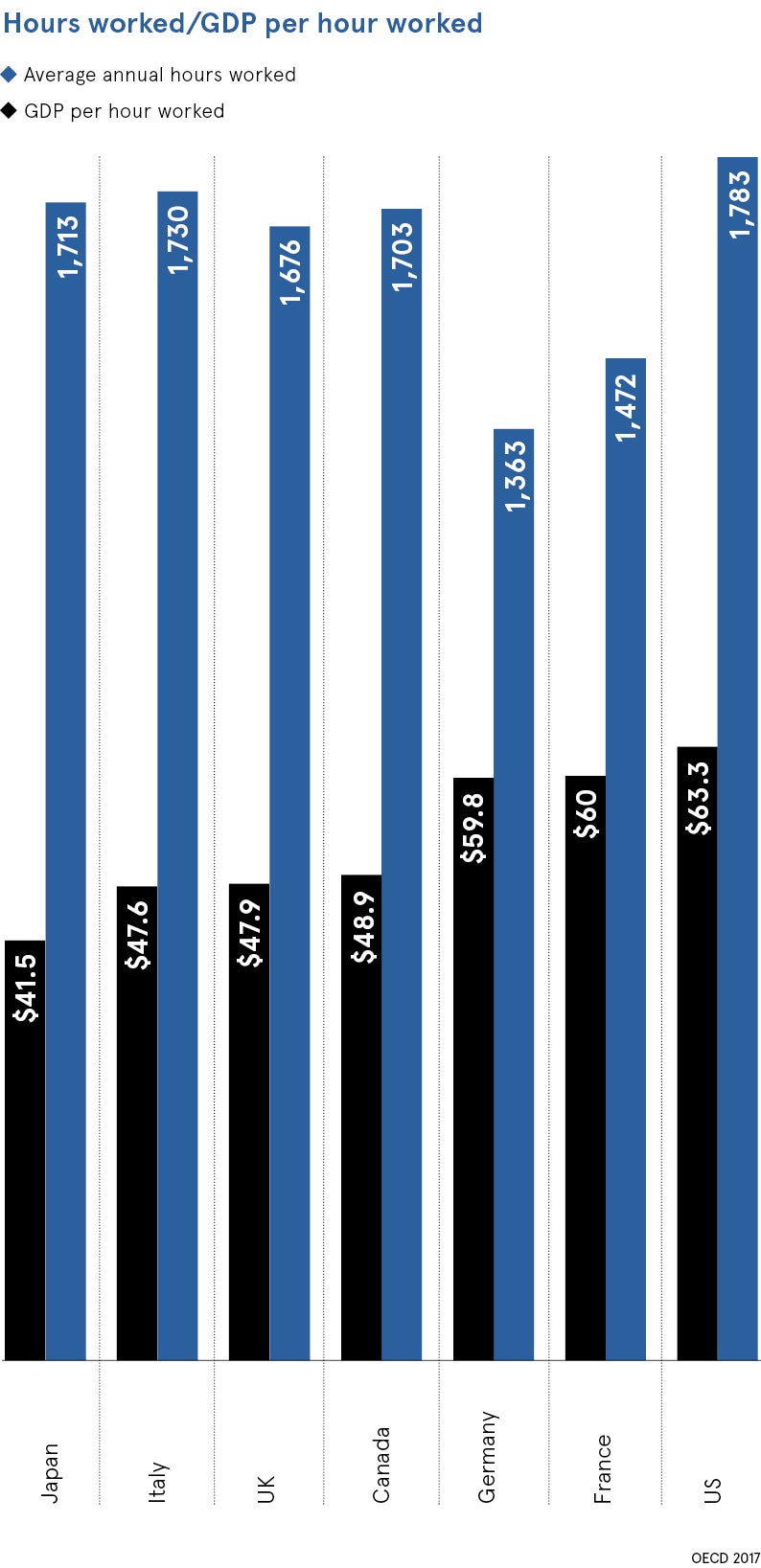

Measuring productivity is not as simple as counting the hours that people spend at work. If the Americans are considered workhorses for putting in an average of 1,783 hours a year, the Germans might be seen as slackers with their annual average of 1,363 hours. Both have higher GDP per hour worked than the UK, where the average annual hours worked is 1,676. Employees in France and Germany may spend fewer hours at work than the British, but while they are there the data suggests they are more efficient and more productive.

There are two estimates of productivity, output per hour and output per worker, and employers in the UK are now looking more closely at workplace behaviours to get a better understanding of the factors that influence worker productivity.

Vicky Pryce, chief economic adviser at economics consultancy CEBR, says: “In some organisations, HR watchers have started to look at whether work habits, particularly those of young people, or negative attitudes to learning ‘trades’, offer part of the explanation.”

But in truth the reasons are more fundamental. Traditional industries, such as mining and quarrying, are seeing declining productivity, and the UK is spending less of its GDP on infrastructure, innovation and research and development, both at government and business level. Manufacturing tends to be more export oriented and invests more on balance, but its share in the UK economy is small, while less productive services dominate. The UK also lags behind on skills, a major contributor to productivity.

Ms Pryce adds: “We have one of the worst literacy and numeracy records for 16 to 18 year olds among the advanced nations, and a small and underperforming technical education sector. The OECD has calculated that raising UK skills level to best country practice would raise UK productivity alone by 5 per cent.”

UK compared worldwide