Visitors to cities like London, Paris, Oslo and Beijing have grown accustomed to the ubiquity of charging points for electric vehicles or EVs. Cars sit silently, plugged into charging stations with sleek designs and unobtrusive neon lights. The stations look minimal and discrete. They are also set to become omnipresent.

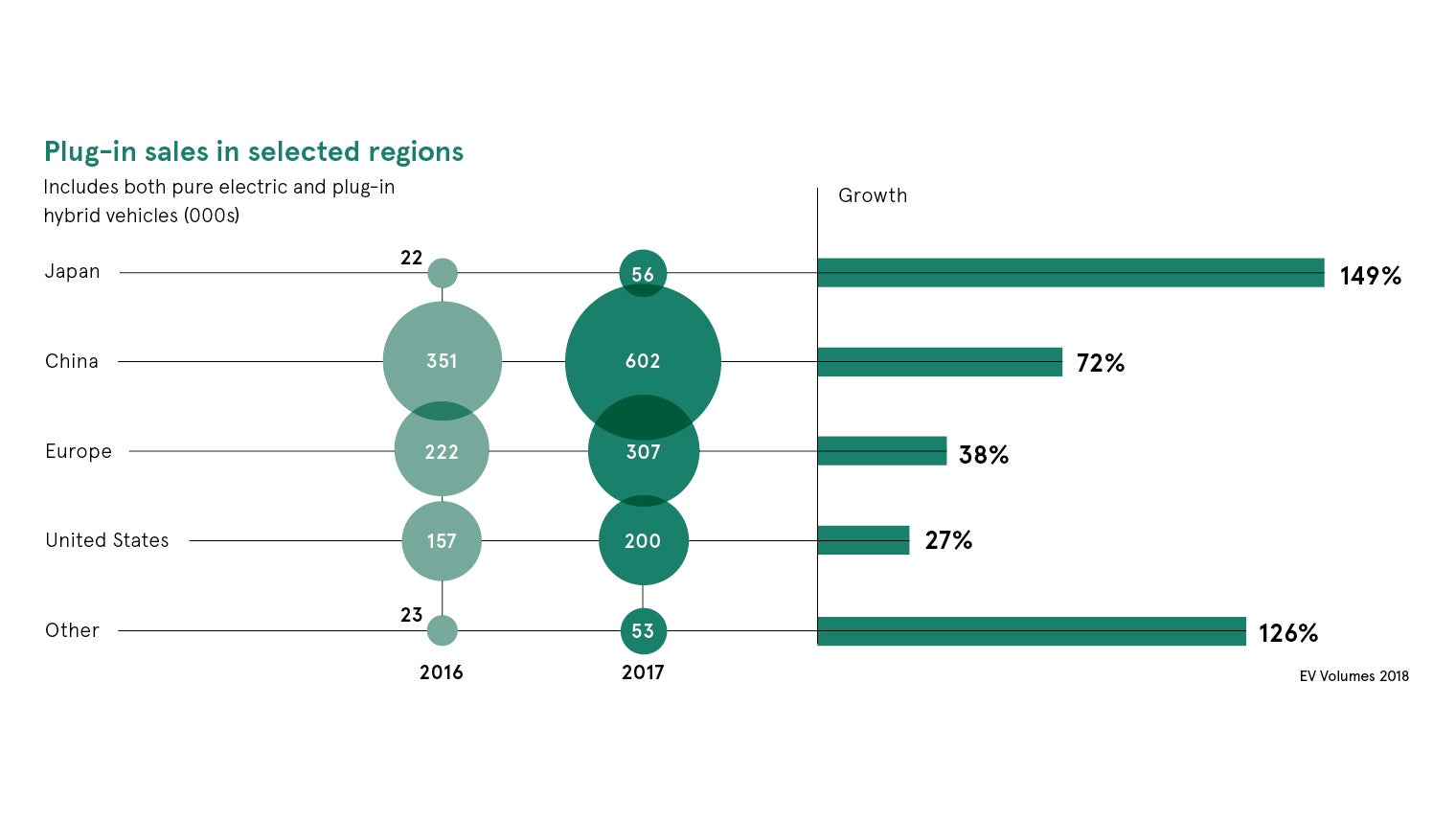

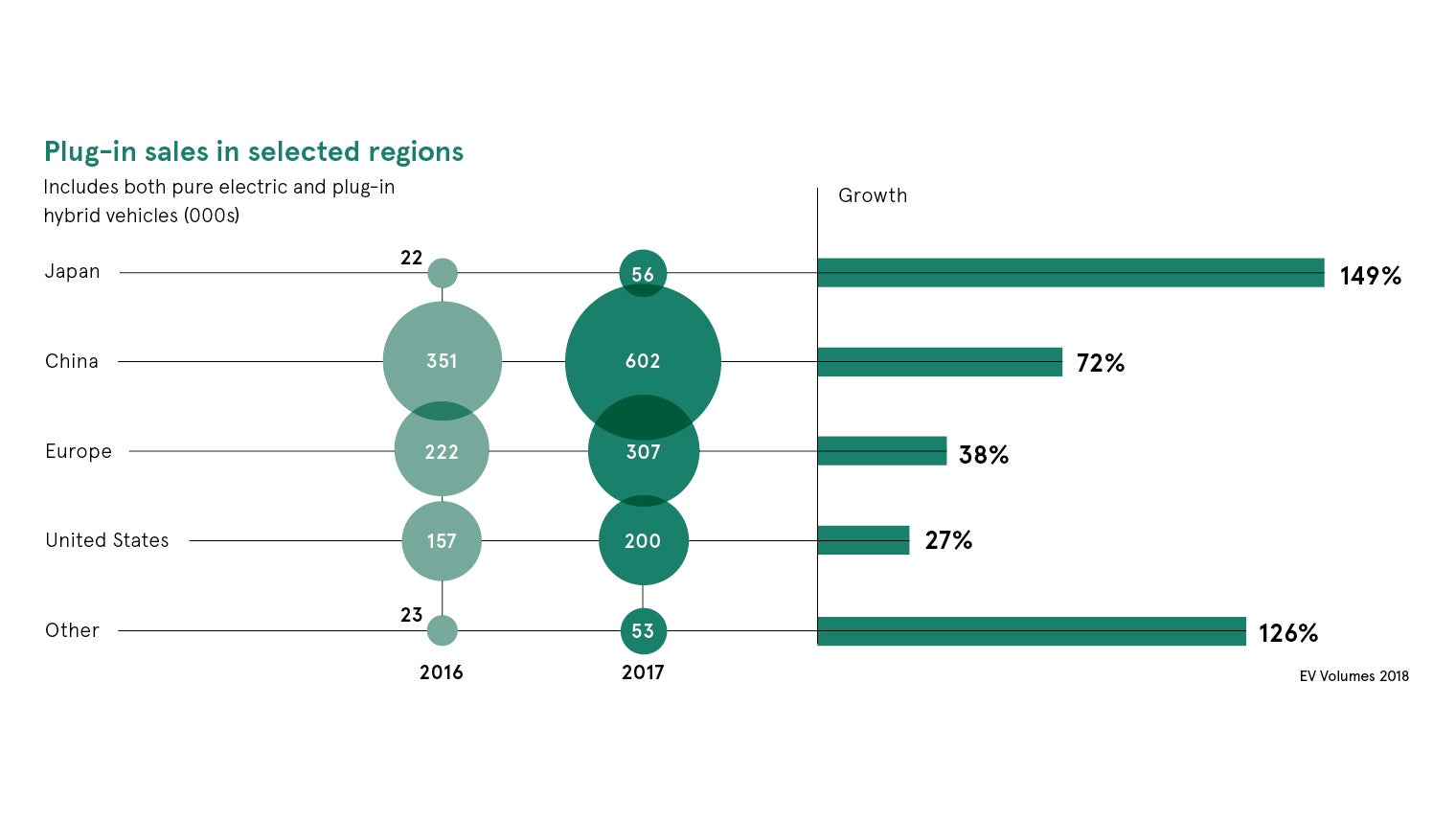

The global market for EVs and related infrastructure has seen a major boost in the last 12 months. According to new research from EV Volumes, which monitors global sales, around 1.2 million EVs were registered worldwide in 2017, a 57 per cent increase on 2016. These figures include sales of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs). China was the global leader with a 72 per cent year-on-year increase, representing nearly half of all sales; the UK ranks modestly at number 13.

In 2018, EV Volumes expects sales to increase by 1.9 million units, resulting in more than five million plug-in cars and light trucks worldwide, owing to the mass production of Tesla’s Model-3 and deeper adoption in China.

“All these new cars will need charging points and infrastructure,” says Viktor Irle, consultant and market analyst at EV Volumes, which is based in Sweden. “In Europe, you can see that countries like Norway, Belgium, Switzerland and Finland are doing well in adapting to electric vehicles.”

While 90 per cent of all EVs are charged at home, drivers living in apartments or those reliant on street charging require developers and local authorities to provide charging points. “As people increasingly move into mixed use communities, these new developments will need to be future-proofed,” says Mr Irle. “One idea is that residents could be able to join together and demand charging points from developers. At the end of the day, future-proofing also adds value to properties.”

The necessity of replacing internal combustion engines has been backed by targets from governments which has caused a related increase in infrastructure investment. Last summer, both the UK and France ruled that any cars reliant on diesel or petrol would be illegal by 2040. The falling price of EVs, prompted by subsidies and an increase in competition – an entry-level Volkswagen e-Up is priced at less than £10,000 – has also helped.

A rise in sales has also seen countries including the UK, Germany, Holland and Norway launch a number of schemes to boost access to public charging. London recently announced plans to roll out 1,500 new charging points by 2020. A number of local authorities have also fitted charging adaptors to street lights.

Last year, Shell opened its first EV charging points in ten filling stations in London, Surrey and Derby; the points can charge most EVs in around 30 minutes. By the end of this year, China will have installed an additional 800,000 public charging points, including those for workplaces, taxis and commercial vehicles.

Fears over a lack of EV infrastructure, combined with the distance travelled by EVs on one charge, were once summed up by the phrase “range anxiety”, the dread that an EV might run out of power before reaching its next charging point. This trepidation has been a little assuaged by an increase in the number of public charge points and EVs which now range up to 300km.

Last year, Daimler, BMW, Volkswagen and Ford said they would work together to install a total of 400 public charging points in Europe, delivering 350 kilowatts, which will charge a small car to three-quarters full in four minutes and a large vehicle in 12 minutes. At the same time, user research has also provided some comfort to drivers. The average daily distance covered by cars in the UK is less than 40km or 25 miles; Americans travel around 70km a day.

Infrastructure is one of the most challenging aspects of building an electric vehicle network

Lee Feihn, UK business developer at NewMotion, Europe’s largest electric charging partner, says: “Infrastructure is one of the most challenging aspects of building an electric vehicle network.” His company launched in 2009 and became a subsidiary of Shell in October 2017. NewMotion designs, builds and supports electric smart charge services, including charging points, a mobile app and charge cards which allow access to 63,500 charging points in more than 25 countries. The company’s first charging points were unveiled in December 2011 at the headquarters of Opel in Holland.

“Infrastructure needs are overwhelmingly on the side of electric cars,” says Mr Feihn. The latest research from NewMotion, which surveyed more than 8,500 EV drivers across Europe, shows many companies have room to improve on EV engagement as only 10 per cent of surveyed EV drivers charge their cars at their workplace. “Homes will need additional charging points, streets require a variety of charging points and traditional fuel suppliers will need to adapt their businesses to lean towards a rise in demand for clean fuels,” he says.

One additional hurdle concerns the cost and maintenance of super chargers on public land. An individual unit can cost around £22,000 to purchase and £45,000 to £50,000 to install. Super chargers also require maintenance from wear-and-tear, the elements and, occasionally, vandalism. “It is an additional complication in cities where most people don’t have a private garage or a driveway,” says Celine Cluzel, associate director at Element Energy, which specialises in providing analysis of low-carbon energy for industrial uses in transport, power generation and buildings.

“If a company buys land and installs chargers, that is relatively easy to do. But if the land is publicly owned, then you have to go into negotiations and tenders, which can be time consuming. For companies that specialise in EV infrastructure, access to electricity isn’t always the challenge – access to land can be harder to negotiate.”