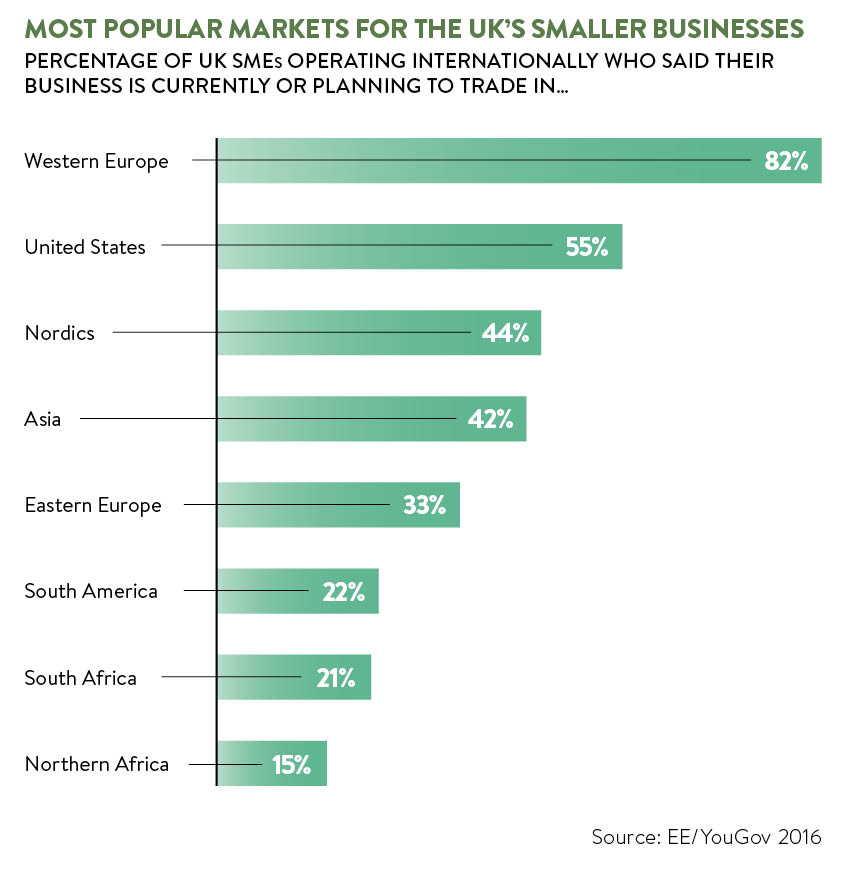

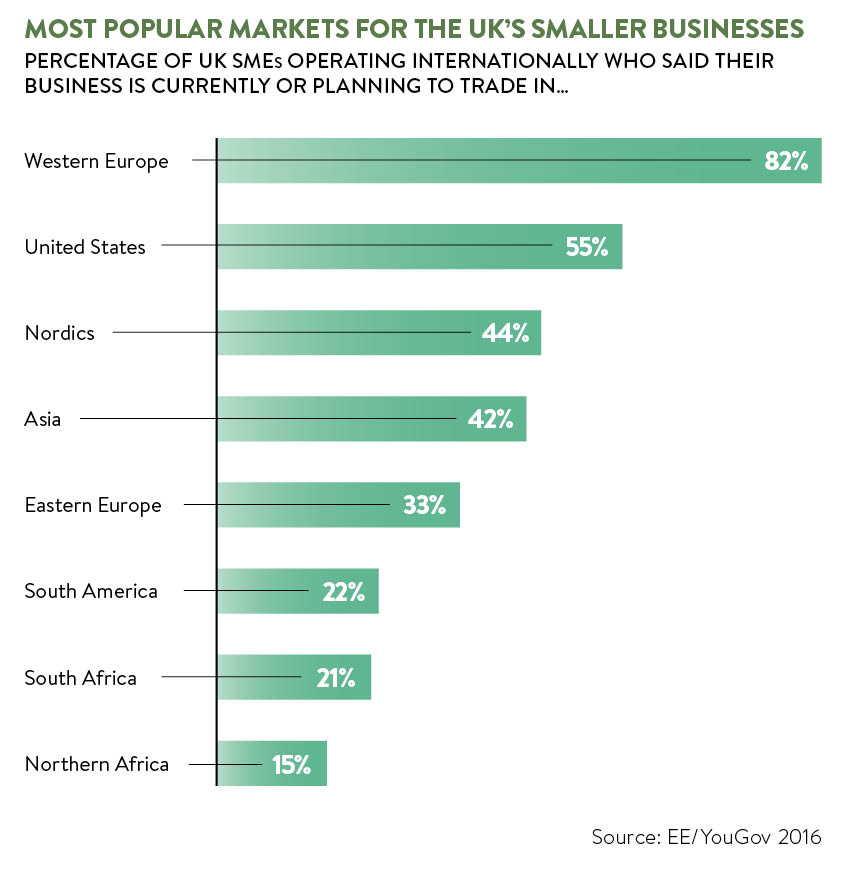

In March a survey of 1,000 small and medium-sized UK businesses revealed 40 per cent trade internationally and another 6 per cent are planning to do so by 2021. The survey, conducted by YouGov on behalf of mobile network provider EE, found 82 per cent are currently or plan to trade with Western Europe and 55 per cent with the United States.

This actual and potential business is underpinned by the ability of firms to make cross-border payments as efficiently as possible. In Europe this is about to change considerably under the European Commission’s revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2). This regulation, due to be finalised in 2017, will force banks to allow third-party service providers to offer payment services to the bank’s customers without putting up any technical barriers. A consumer could sign up to a payment app and it would be able to make transfers to and from their account on their behalf.

“There are probably a couple of interesting areas for merchants; one is access to bank accounts and I think the other is the requirement for two-factor authentication to be undertaken on every transaction within the European Economic Area,” says Iain McLean, head of retail development at MasterCard UK and Ireland. “I think banks are very well prepared for this, yet retailers, even large retailers, haven’t quite appreciated the impact it could have for their business.”

The effect on retailers

The potential this holds for financial technology (fintech) firms to disrupt the payments space is considerable. In the Capgemini/BNP Paribas World Payments Report 2016, 71.4 per cent of banks and 69.7 per cent of non-banks thought fintech firms were a challenge for transaction banking. If fintech firms develop new technologies to facilitate payments, they could potentially disintermediate banks from the transaction part of the payments business.

The potential this holds for financial technology (fintech) firms to disrupt the payments space is considerable. In the Capgemini/BNP Paribas World Payments Report 2016, 71.4 per cent of banks and 69.7 per cent of non-banks thought fintech firms were a challenge for transaction banking. If fintech firms develop new technologies to facilitate payments, they could potentially disintermediate banks from the transaction part of the payments business.

The primarily effect is likely to be around consumer experience and protection, for example an improvement of acceptance or failure rates.

The growth of digital business removes the physical element of cross-border operations

Simon Bailey, director for payments and transaction banking at technology provider CGI, says: “There are a set of technology changes going on underneath payments, some of which are slight improvements on the current arrangements, some of which are radically new approaches, but which should be invisible to a corporate because, if they are visible, frankly they are not working.”

Digital-first

The growth of digital business removes the physical element of cross-border operations; Uber, Airbnb and Alibaba are companies that were born online, with few physical assets, and can operate across borders as long as transactions can be made. But digital is also changing the way transactions are made.

“Uber drivers needed to be paid all over the world and expect the payment to come instantly, so it’s changing the demand in financial services infrastructures,” says Danny Aranda, managing director of Ripple Europe. “That’s what we believe our opportunity is. If you look at many innovations over the past 20 years in financial services, it’s largely been at the interface level, meaning a better mobile application or a better online user experience. We really want to bring some element of the internet into the infrastructure of financial services.”

Ripple builds distributed ledgers, essentially shared databases that record transactions between everyone that shares the database. Instead of two banks operating their own independent databases and then having to reconcile the figures between them, the use of a single ledger for transactions means there is no need to double-check who has what. Everyone can see what is where and transfers can only be made if the database shows that funds area available. It reduces a lot of the technical complexity that can exist between multiple payment systems and allows many stages of the process to be automated.

In May Santander announced it would be using Ripple technology to facilitate cross-border payments from the UK via an app connected to Apple Pay. Using fingerprint ID, the app will allow transfers of up to £10,000 into euros or US dollars. Standard Chartered is developing a use-case in Singapore for corporate clients.

In July Belgian bank KBC said it had developed a digital ledger with technology firm Cegeka. For use by smaller businesses, it can connect buyer, seller, KBC and the counterparty’s bank using a smart contract that registers the entire trade process from order to payment with payment guaranteed when all contractual agreements have been met. The bank is currently exploring connections with other European Union banks as 77 per cent of Belgian exports are to that region.

The e-commerce trade

MasterCard’s Mr McLean says certain corridors dominate from an e-commerce trade perspective, with the UK typically looking at US and then larger European markets, such as Germany, France and Italy. The corridor and scale of business will determine whether a firm can use certain transactional channels. If corporates are looking to make international payments, the number of mechanisms they can use is relatively high taken at face value.

“There are many remittance companies and foreign exchange firms in the retail to low-end commercial transfer space,” says CGI’s Mr Bailey. “For larger transfers, using commercial banking is easier or harder depending on the corridors they are considering. Most banks are derisking and the risk aversion caused by things like anti-money laundering regulation can make banks less comfortable dealing with certain transactions.”

There are three issues for companies to consider, advises Mr McLean. “Firstly, it is about the technology, understanding consumers in these markets and how they like to pay, then adopting the right technology to serve that,” he says. “Secondly, understand any barriers to payments – authorisation and authentication, for example. The third point would be understanding consumers and how to gain traction within those markets. Places like the US are large and attractive, but they are very challenging.”

The internet really informs the way we expect services to be delivered

Many payment mechanisms have relied upon banks to cover a payment during a transaction, using money on their balance sheet. Where banks are pulling back from offering this, as part of the derisking process, firms can look for technology and service providers that can step in.

URICA is one example, using the resources of insurer RSA and credit-related insurance provider Euler Hermes to provide firms with payment for invoices that customers have not yet paid in export markets. This can replace bank services, such as letters of credit and increasingly rare bank-guaranteed bills of exchange, or taking credit risk by invoicing with terms of payment.

The extent to which banks or non-banks will provide payment services to corporates in the future will depend upon their ability to match both the needs and expectations of their customers.

“Consumers’ and businesses’ expectations of how payments should be conducted have changed,” says Ripple’s Mr Aranda. “That’s largely informed by the internet; if I send a text or an e-mail to someone, I expect them to receive it immediately. If I send a package to Cambridge, I expect to be able to track it online for visibility. The internet really informs the way we expect services to be delivered.”

The effect on retailers

Digital-first